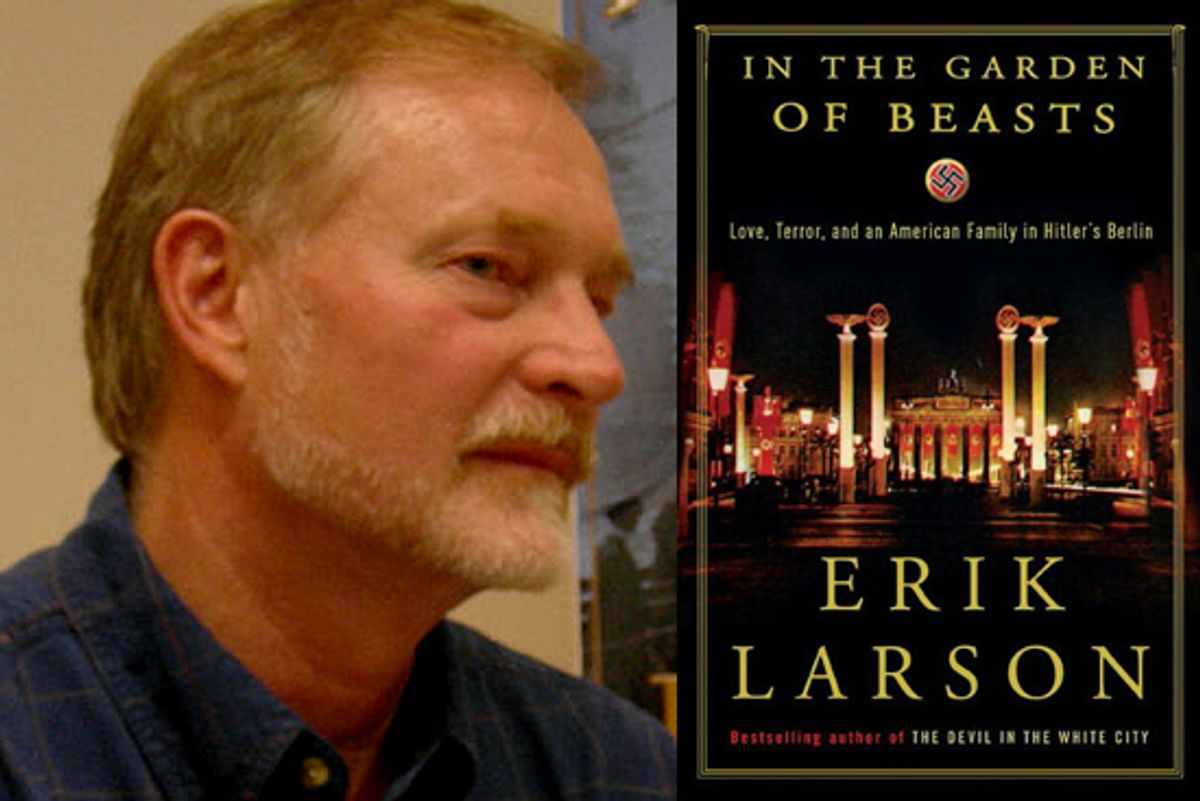

Erik Larson's best-known narrative histories, "The Devil in the White City" and "Isaac's Storm," have been about extraordinary people and events: serial killers, visionary architects, hurricanes. His newest book, the engrossing "In the Garden of Beasts," has a remarkable setting -- Berlin in the mid-1930s as Hitler consolidated his power over every aspect of German life -- but the people he writes about aren't particularly exceptional.

That's the point. In the book's prologue, Larson tells of his long-standing interest in what it was like to witness the "gathering dark of Hitler's rule." Certain perceptive individuals could see exactly where Germany was going, but the vast majority did not. You could even say that the rise of the Third Reich is primarily a story about what regular people failed to notice or to take seriously until it was too late. The two Americans Larson has chosen to focus on in this book are William Dodd, who was the U.S. ambassador to Germany from 1933 to 1937, and his daughter, Martha, who socialized with many crucial figures of the period.

"In the Garden of Beasts" dwells primarily on the first year of Dodd's tenure in Berlin, from the summer of 1933, when the ambassador and his family arrived, willing to give the new government the benefit of the doubt and stirred by Germany's mood of energetic renewal, to the summer of 1934, when they were utterly disillusioned and repulsed. The climactic event is the Night of the Long Knives, June 30, 1934, when Hitler ordered a political purge that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of his critics and rivals, many of them friends and acquaintance of the Dodds.

William and Martha Dodd weren't entirely ordinary people, of course, but neither were they especially shrewd or insightful. The chairman of the history department at the University of Chicago, Dodd was something like seventh or eighth on FDR's list of candidates for the post; none of the others wanted the job. Intelligent and hardworking, a "Jefferson Democrat" with a penchant for amateur farming and a man of unimpeachable integrity, Dodd had hoped for an assignment to an undemanding country like Belgium, where he'd have the time to work on his magnum opus, a history of the antebellum South. He was ambivalent from the start, claiming not to be "the sly, two-faced type so necessary to 'lie abroad for the country.'" That's a pretty fair self-assessment; he had little gift for diplomacy.

Martha was in her mid-20s, pretty and bright but (by her own measure) "flighty." She'd been the assistant literary editor of the Chicago Tribune and had an affair with Carl Sandburg and a deep friendship with Thornton Wilder. An old friend compared her to Scarlett O'Hara -- another fair assessment, as she made a habit of flirting and playing her suitors off against each other. By the time she decided to accompany her father to Berlin, Martha already had a secret marriage under her belt, although she and her banker husband were estranged.

In Berlin, Martha's escapades (she had affairs with several Nazis, including Rudolf Diels, the first commander of the Gestapo, and one of her ex-lovers even tried to fix her up with Hitler) quietly scandalized the locals. "I must have appeared a most naive and stubborn young American, a vexation to all sensible people I knew," she would later observe. She was also swayed by the theater of Nazi politics (which was designed to appeal to adolescent mentalities exactly like hers), writing to Wilder: "Wholesome and beautiful lads, these Germans, good, sincere, healthy, mystic, brutal, fine, hopeful, capable of death and love, deep, rich, wondrous and strange these youths."

Her father had a leveler head -- perhaps too level. His great weakness, according to Larson, was that he saw the world "as the product of historical forces and the decisions of more or less rational people." Although born and educated in the South, he resembled the quintessential Midwesterner: industrious, conscientious, principled and self-effacing but also a bit dull. It did not help that he harbored what Larson calls a "rudimental anti-Semitism" and once told the German foreign minister, "We have had difficulty now and then in the United States with Jews who had gotten too much of a hold on certain departments of intellectual and business life." Like many, many Americans at that time, Dodd expected Hitler's reign to be short-lived and regarded reports of Nazi persecution and harassment as exaggerations or isolated incidents.

Their first year in Berlin stripped both Dodds of such comforting illusions. (Dodd's wife and grown son were also with them, but William and Martha left the most extensive written accounts of their German years.) Martha, whose circle included both members and critics of the regime, finally got the message when she and a dissident friend paid a visit to the author Hans Fallada, who had supposedly come to some sort of accommodation with the Nazis. "I saw the stamp of naked fear on a writer's face for the first time," she recalled, although considering some of what she had witnessed before that, she could well be faulted for not taking the terrorizing of non-writers more seriously. Martha also commenced a passionate affair with a staff member of the Soviet embassy, and this stoked her growing interest in communism. (He turned out to have considerably mixed motives.)

William Dodd eventually grasped what he was dealing with in Germany, although he held out hope that Hitler would self-moderate for a surprisingly long time. It was seeing the Führer fume maniacally about "the Jews" that finally impressed the truth on him. After he returned from Berlin, Dodd went on speaking tours around the States, warning his fellow Americans of Hitler's murderous, imperialist intent and the futility of isolationism; it would earn him a reputation for foresight. However, the U.S. consul general, George S. Messersmith, knew all of this even before Dodd arrived in Germany, and sent many similar warnings back to Washington, to little effect. The administration and Congress were preoccupied with the Depression and the droughts that had turned the prairie states into dust bowls; their priority was coaxing the Germans into repaying the millions of dollars they'd borrowed from American creditors.

Why did it take Dodd so long to wise up? Partly, you just had to be there for a while, as Messersmith had, but the ambassador was also distracted. "In the Garden of Beasts" provides an excellent case study in the folly of sweating the little stuff. Dodd was often caught up in battling the "Pretty Good Club," a cadre of wealthy men who accepted ambassadorial appointments and maintained lavish standards of living and entertaining in foreign capitals. The frugal Dodd wished to make the State Department more "democratic" and practical, and insisted on living on his own humble salary. He also squandering any store of good will back home by perpetually scolding his colleagues for their profligacy -- lengthy international cables made him particularly irate.

The State Department's elitism was a real problem, so Dodd had a point. It's just that it was a relatively trivial point compared to the threat posed by the Nazis' burgeoning power and militarism. The patricians back home, not surprisingly, bridled at his nagging and wrote him off as a tedious, penny-pinching prig who lack the imposing style required to bring the Germans to heel. When he really needed their help and support, he would find himself flapping in the wind.

Whether Dodd could have done much to restrain Hitler isn't clear -- Larson seems to think not. When he finally understood what he needed to do, he certainly tried his best, and behaved with courage. Perhaps a man more suited to "lie for the country" (in other words, a worldlier person with more charm) might have made a difference. At the very least, William and Martha Dodd's story serves as a reminder of how easy it is to be mistaken about what really matters.

Shares