During the mid-2000s, Scott Carney was living in southern India and teaching American anthropology students on their semester abroad when one of his charges died, apparently a suicide. For two days, he watched over her body while the provincial police investigated her death, reporters bribed their way into the morgue to photograph the newsworthy corpse, local doctors performed an autopsy, and ice had to be rounded up to retard decomposition. Finally, his boss asked Carney to take pictures of the girl's mangled remains for analysis by forensic experts back in the States.

This unsettling experience gave Carney his first inkling of how a human being becomes a thing. When he abandoned academia for investigative journalism (he writes for Wired, Mother Jones and other publications), his South Asian surroundings offered him many examples of the ways human bodies -- in part or in whole -- are transformed into commodities. He calls this the "red market," a term that encompasses the trade (legal and illegal) in human bones, blood, organs, embryos, surrogate pregnancy and living children.

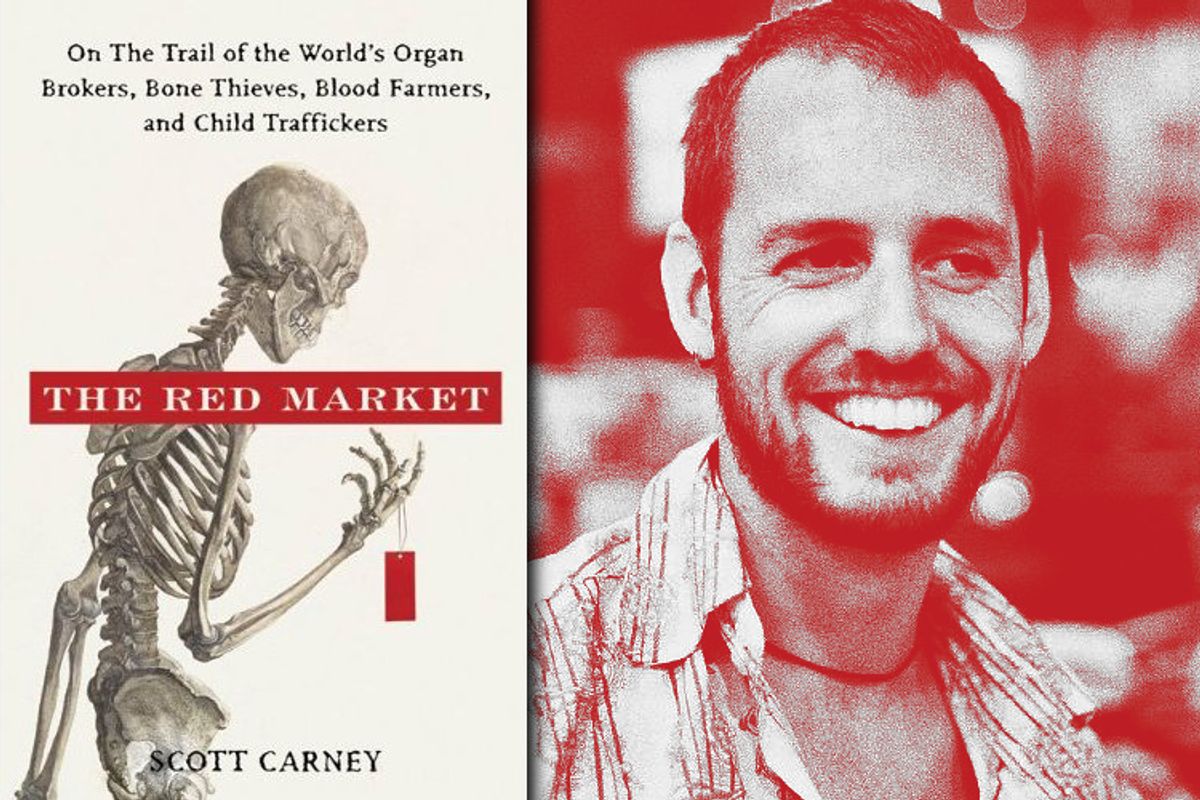

"The Red Market: On the Trail of the World's Organ Brokers, Bone Thieves, Blood Farmers, and Child Traffickers" is the alarming product of Carney's research. It includes vivid, on-the-spot reports from Indian "bone farms," where remains looted from graveyards are processed into skeletons for Western anatomy students (hundreds of reeking bones left out to bleach in the sun) and tsunami refugee camps where most of the residents bear the scars of kidney "donations." Carney relays these tales with enough florid touches ("Toads the size of baseball mitts hop across the muddy track") to make them seem downright hallucinatory.

Freakish as these stories can be -- none more so than the dairy farmer who kept several men prisoner in sheds, some for more than three years, extracting their blood to sell to a nearby hospital -- they are the secret face of the age of modern medical miracles. Poor people supply human flesh in various forms for rich people, while a well-meaning ethical system of anonymity and mandated "altruism" allows middlemen to siphon off most of the profits.

When the supply isn't sufficient to the demand, some enterprising individuals take it upon themselves to even things up. One of the most heartrending stories Carney tells is of an Indian family who bankrupted themselves trying to find their son, who was kidnapped by an orphanage and essentially sold to an American adoption agency. The Midwestern couple that may have adopted the boy are resisting attempts to establish the child's identity, even though the Indian father tells Carney he understands "it's not realistic for us to ask for him back, but at least let us know him."

Denial makes such injustices possible. Carney argues that the inequities of the red market were only exacerbated by regulations like the National Organ Transplant Act of 1984, which prohibited the sale of human organs and tissue and was championed by then-Sen. Al Gore as a way to make sure that the human body could not be treated as "a mere assemblage of spare parts." Although Carney is no fan of the market philosophy that would reduce our bodies to salable "widgets," he thinks we need to face up to the fact that altruistic donation will never provide as much of these precious materials as we desire. "As a society we neither want to accept open trade in human tissue, nor do we want to reduce our access to life-extending treatments. In other words, we want to have our cake and eat it, too."

He also thinks "absolute transparency of the supply chain" would go a long way toward eliminating the brokers, recruiters and suppliers who exploit those driven to trade their kidneys and blood for cash or to rent out their wombs. "Every bag of blood should include the name of the original donor, every adopted child should have full access to his personal history, and every transplant recipient should know who gave him an organ," he writes. (Contrary to what you see in the movies, much of this information is sequestered by what Carney regards as "misguided" privacy laws.) Yes, the hustlers will immediately commence forging documents, but even so, "a clear paper trail makes it easier to flag dangerous operators."

And while he doesn't come right out and say it, Carney obviously thinks the world's privileged patients ought to revise their expectations and reconcile themselves to their mortality. He more or less implies that the handful of years most kidney transplant recipients gain from the operation may not be worth the cost in exploitation. (Most Indian "donors" get as little as $800 for their organs -- though some are promised more -- not enough to make a significant difference in their circumstances or lift them out of destitution for more than a year or so. This is out of the $14,000 or so paid by the recipient for the transplant.)

No doubt Carney doesn't linger on this point because he knows it's a nonstarter. Most people would countenance a good deal of dodgy behavior if it meant a few more years of life for themselves or a loved one. Nevertheless, it makes sense that they be made aware of how much their survival may have cost others, and Carney rightly decries the "depersonalization of human tissue" that obscures that cost. This challenging and revelatory book makes it a little bit harder to overlook the human being in every human body.

Shares