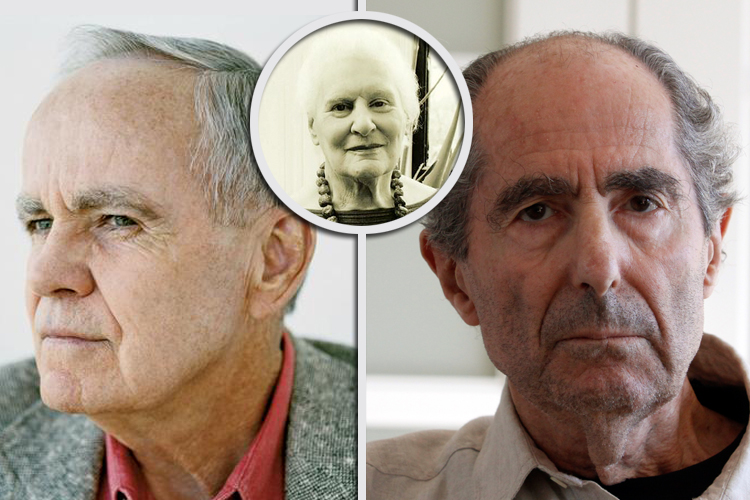

A remark Philip Roth made in the Financial Times over the weekend has provoked much comment: “I’ve stopped reading fiction,” the 78-year-old author of “Portnoy’s Complaint” and dozens of other novels said. Roth isn’t alone; over the years, such writers as Cormac McCarthy, Will Self and William Gibson have made similar statements.

Some people don’t like fiction and never have. That’s quite different from having once read fiction avidly and then, in the fullness of time, giving it up. To judge informally (that is, according to what people tell me when they learn I’m a book reviewer), the latter is far from an uncommon experience. Many former devourers of novels haven’t stopped reading, they’ve just come, like Roth, to prefer nonfiction books on history, science or politics.

Roth, when pressed by his interlocutor, didn’t offer much of a reason for the change in his tastes: “I don’t know. I wised up …” he said rather enigmatically. It may be that he’s determined that reading other people’s novels impairs his ability to write his own. Most writers know what it’s like to fall under the sway of a master’s voice and to wind up unwillingly imitating it. Self told an interviewer that he couldn’t enjoy other authors’ fiction because “It uses the same muscles that I use to write with.” Still, it’s improbable that a writer with a voice as established as Roth would have this problem.

Perhaps, like McCarthy, Roth has simply lost interest. (McCarthy once said that he found reading fiction “a rather odd thing to do.”) Non-writers who have bailed on novels and short stories often say they’ve exhausted their patience for flagrantly “untrue” narratives. One blogger explained it thus: “I put it down to having experienced enough real life narrative and drama such that made-up stories no longer appeal.”

There’s a school of evolutionary anthropology that might agree with him. It speculates that fictional storytelling — a universal cultural practice — helps people imagine what others are thinking and feeling, and consequently how they might behave in the future. The value of such skills when it comes to navigating complex social groups is obvious, but perhaps people do reach a saturation point with age. No other artistic form can surpass the novel’s ability to immerse us in the inner life of another human being, yet there may come a stage when that prospect promises nothing new.

The literary journalist Sarah Weinman rose to Roth’s defense on Twitter, writing, “Actually, I am more surprised when 70-something writers read fiction. V. Rare.” Intrigued, I asked her to expand on this remark, and she told me, “To read fiction in particular is to engage with so many different creative senses, from being knocked out by a great writer’s examination of the human condition to marveling over linguistic style and voice to escapism and entertainment, or even all of the above. And as one gets older, and the ability to free up space in one’s head to properly engage with reading and not be distracted by physical and/or mental ailments, it seems to me that reading fiction would naturally become more difficult.”

Or maybe what some readers get sick of is introspection itself. The celebrated memoirist Diana Athill spent her working life reading as well as editing fiction, but wrote that in her 90s she had “gone off novels.” She blames this on the loss of a certain narcissistic taste that once dominated her reading. “Because a great many of today’s novels still focus on the love lives of the kind of women I see around me all the time, that means I am bored by a large proportion of available fiction,” she wrote in “Somewhere Towards the End.” I can sympathize. Once, the struggles of 25-year-olds to satisfactorily arrange their romantic lives was a fascinating topic to me. Now, not so much.

Of course, that’s only one kind of novel, in a world that offers many, many choices. It’s hard to muster the energy to explore new genres, however, when you’ve lost your faith. As champions of nonfiction often point out, whatever the literary shortcomings of any given work of nonfiction, at the very least you come away from it having learned something about the world. Fiction, however, doesn’t offer instruction or information; it offers an experience. And for that experience to occur, the reader has to deliver him- or herself up to the book.

This takes faith — belief that it can be done and trust that the author can do it. As Weinman suggests, you have to clear space in your head, like a party host pushing back the furniture, stocking up on drinks and hoping that everyone invited will come. If the gamble pays off, if the guests show up in a festive mood and hit it off with one another, you have a fabulous time. If the party never gels, all you have to show for your efforts are disappointment and embarrassment.

I don’t think fiction is harder to read than nonfiction — if anything, good fiction (make that the right fiction) is easier. But, as every reader can attest, opening a novel is a crap shoot. Depending on how new and untried the books you read are, the washouts are likely to outnumber the successes. For some older readers, summoning the optimistic energy required to give it yet another go despite these discouraging odds just doesn’t seem worth it. As Dr. Johnson said of second marriages, such efforts represent the triumph of hope over experience.

Yet others are still willing to try, like the late John Updike. “It frankly amazes me,” Weinman noted, “that he still reviewed younger writers for as long as he did.” I expect he threw some great parties, too.

Further reading

The original Financial Times interview with Philip Roth

Will Self tells the BBC that he doesn’t read fiction

Readers of Mike Johnstone’s blog discuss their diminishing interest in fiction