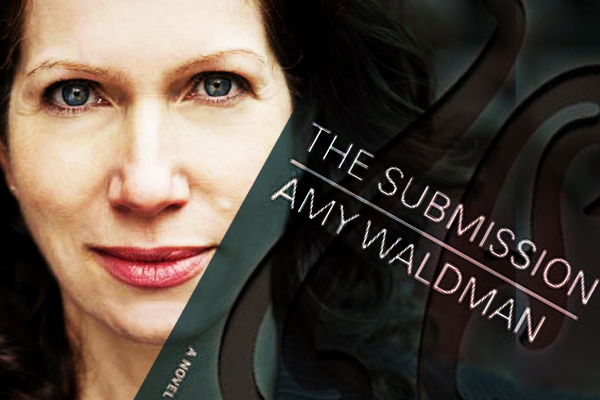

The premise of Amy Waldman’s powerful first novel, “The Submission,” can be distilled readily enough: Two years after New York City is struck by a catastrophic terrorist attack (essentially identical to 9/11, although never identified as such in the book), a jury selects a design for the memorial in an anonymous competition. Then they discover that the architect of their choice is a Muslim American.

A high concept, indeed, yet it’s all too easy to imagine how film studio executives might pick apart “The Submission” if it were, say, a screenplay. “Whose story is this?” they’d ask. “Who are we supposed to identify with?” Is the main character the juror chosen to represent “the families,” Claire Burwell, a cool, rich blonde whose husband died in the towers and who champions Mohammed “Mo” Khan’s design from the start? Or is it Mo himself, an elegant secular Muslim who refuses to address the predictable controversy that soon billows around the jury’s decision? Or is it Asma Anwar, the widow of a Bengali janitor also killed in the attack, but, as an illegal immigrant, shut out of the rituals of public mourning? Or could it be one of the dark horses in the story — jury chairman Paul Rubin, in charge of the whole project, or family-member activist Sean Gallagher, a one-time working-class screw-up who in a single day lost a brother and gained a cause? Could it even be Alyssa Spier, the tabloid reporter who parlays the news of Mo’s selection into a columnist gig at the New York Post?

“The Submission” clicks through the points of view of each of these characters like a carousel slide projector, each time offering a different perspective tinted by a different fall of light. Furthermore, the characters’ own thoughts and feelings about the memorial — should Mo and the jury insist on pushing his design through? Should the public be allowed to override them? Should Mo withdraw in the interests of national “healing”? — are constantly shifting. Whoever gets charged with turning this book into a movie (that is, if it ends up being as successful as it deserves to be) cannot be envied. As a popular entertainment, “The Submission” lacks heroic focus and a decisive notion of who’s right and who’s wrong.

These are also the qualities that make “The Submission” so satisfying as a novel. Waldman does what only a novelist can do: provide her readers with access to the protean inner lives of a half-dozen conflicted individuals, each with his or her own peculiar history and partial perspective on the world. In direct, uncluttered prose (there’s no time to be vague or allusive with so much psychic territory to cover), Waldman charts the evolution of the memorial controversy, a media circus in which each participant’s position is simultaneously understandable and untenable.

In the New York Times, Michiko Kakutani favorably compared “The Submission” to the ostentatiously “social” novels of Tom Wolfe. That’s reasonable, but a more fitting bookend would be last year’s “Freedom” by Jonathan Franzen; Waldman, unlike Wolfe, is no polemicist, and her theme and title are the shadows of Franzen’s freedom. The submission is both Mo’s entry in the design competition — a geometrical garden that his critics interpret as a “martyr’s paradise” — and the derivation of the word “Islam,” which signifies surrender to the will of God.

Each of the novel’s characters must decide what he or she will submit to. Sparring with a snooty jury member who initially rejects the garden as “too soft … Designed to please the same Americans who love Impressionism,” Claire doesn’t hesitate to call upon the emotional authority of her own loss. But, having done so, how can she then disregard the objections of family members like Sean’s father, who tells the New York Times that he objects to Mo’s design because “They killed my son. Is that reason enough for you? And I don’t want one of their names over his grave.” Should she serve the constituency she supposedly represents on the jury, or the memory of her husband, who she believes would want the garden? For his part, Mo is compelled to choose between the dictates of his ambition and his own bristly pride — “Why should I be responsible for assuaging fears I didn’t create?” he demands of Claire. And as for the jury, they’ll have to decide between commitment to the process and bowing to public opinion.

Ambivalence about democracy lies at the heart of Waldman’s novel. For New York’s politicking governor (determined to ride this thing to the White House), that’s not a problem. Initially vetoing a jury consisting entirely of family members (“We don’t want a bunch of firefighters deciding to put a giant helmet in Manhattan”), she smoothly switches to demagoguery when it suits her ends. Alyssa, likewise, never wavers from her shabby sense of vocation: “A tabby all the way — that’s what she was. She had no ideology, believed only in information, which she obtained, traded, peddled, packaged and published.” (Waldman, a former New York Times reporter who covered 9/11, can be hard on her former colleagues.)

But if Waldman’s pragmatic characters are often contemptible, the impassioned ones are worse. Waldman has a magpie tendency to tuck scraps from real news stories into her fiction. One of her most absurd characters is manifestly based on the garish anti-Muslim blogger Pamela Geller. Sean soon has cause to regret linking his group with hers, a brigade of dementedly energetic, slogan-chanting women who carry around copies of the Quran with the inflammatory passages marked out with orange highlighter. More unnerving is the transformation of Sean’s mother from grieving parent to implacable matriarch as she prosecutes the campaign against Mo’s design as if it were a blood feud.

Sean’s scenes are among the novel’s best. If Franzen is the more accomplished stylist, Waldman is a keener social observer, and this is nowhere more evident than in her handling of the class friction that underlies Sean’s interactions with Claire and Paul. The four pages in which Paul, finally consenting to meet in a power-broker hangout, succeeds in making Sean feel comprehensively impotent, “a no-name worthy of addressing but not worthy of knowing … An audience, not a player,” are an acute précis of 21st-century America’s political resentments. Blundering into bad company and booby-trapped political stances, Sean never entirely falls out of the reader’s sympathy. He means well enough: That’s his tragedy.

“Sometimes,” Mo tells his father, “America has to be pushed — it has to be reminded of what it is.” Waldman’s novel doesn’t push — what novel can, these days? But it does explore, shrewdly, persistently and compassionately without resorting to easy answers or cheap heroics. And that makes it the best reminder of all.