The characters in Kate Beaton's hit webcomic, "Hark! A Vagrant," are familiar, and also not. There are the three Brontë sisters, checking out surly guys: "So passionate!" "So mysterious!" "So brooding!" swoon Charlotte and Emily, while Anne Brontë (author of "The Tenant of Wildfell Hall," in case you didn't know she existed), retorts, "If you like alcoholic dickbags!" "No wonder nobody buys your books," hisses Charlotte. Inspector Javert from "Les Misérables" is detailed to the Bread Crimes Division. Raskolnikov tips off his own police nemesis by penning an Op-Ed titled "Murdering Old Ladies: Not Even a Big Deal."

Beaton, a native of Nova Scotia who recently relocated to Brooklyn, N.Y., began writing comics about historical figures and characters from literature for her college newspaper; her first strip offered tips for surviving a Viking invasion of campus. "The response was way bigger than I ever imagined," she said recently over lunch. "I knew that I had something."

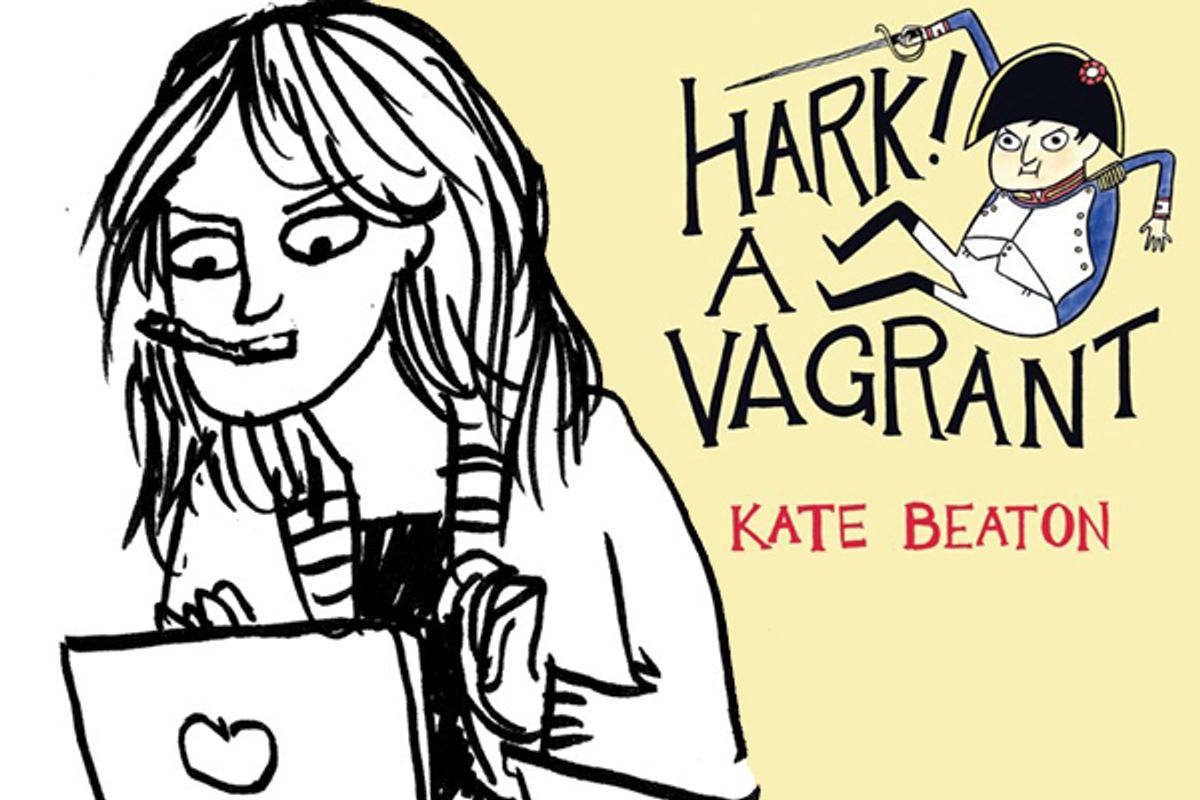

That something became a popular website and now a book, also titled "Hark! A Vagrant" (a line from an old comic), just published by Drawn and Quarterly. I sat down with Beaton to ask her about the art of being funny about history and books.

You were a history and anthropology major in college. Do you have a favorite historical period?

I gravitated toward the 18th and 19th centuries. It was a time of real change, especially for the lower classes and for women. The seeds of all of these movements were happening: workers revolting, unions starting, people breaking off from monarchies. It was action-packed, the birth of our modern society. Before that, it was, "If you're poor, you're poor. If you're a woman -- Sorry!"

What about favorite authors?

I love Shakespeare, and I love Dickens. He is one of my favorites.

I don't recall you doing many comics about Dickens, though.

It's hard because his novels are funny anyway. How do you take a character like Mr. Micawber [from "David Copperfield"] and stretch him out into a joke? He's already a joke. Even the evil guys are so evil, how do you exaggerate that? You can see his influence in my work, if you look for it. There's that wish for a charming presentation.

What do you mean by that?

I want to make something that will make people feel good. If you write a comic about somebody that makes fun of them, you can't just tear them to pieces. You have to celebrate the things that make them memorable. I do a fair service to the people I'm making fun of, even if I'm making fun of them. If I choose a historical figure or a book, it's going to be somebody's favorite. And they'll be the ones who like it the most. If you make in-jokes about Chopin, then people who love Chopin will think it's just the best thing.

Are certain types of books or historical figures better candidates for the kind of satire you do than others?

Definitely the ones that more people have read. When I do historical figures, I feel better going to obscure territory. You can Wikipedia a historical figure and get the gist of things. But you don't want to ruin a book for somebody. So I tend more toward books people read in high school, which a lot of 16-year-olds are forced to read to begin with.

Then, stuff that takes itself very seriously. That's the easiest to lampoon, for sure. People have been doing this for ages. After [Samuel Richardson's novel] "Pamela" came out [in 1740], Henry Fielding wrote a book called "Shamela." Pamela was so virtuous, so perfect, that she made this lecherous, awful man who was chasing her turn into a virtuous person. That was totally unrealistic, and everyone said, "What?!" It's fun to take down things that are not that self-aware. When you make a joke about Jane Eyre, it might be about how Mr. Rochester comes across as a weird, sketchy dude. If someone just gave you the facts about Rochester, you'd think, "This guy is not on the level."

Is there anything in particular that you do to prepare when you want to write a comic about a book?

I'll read essays on it, and people's opinions. That gives you an overview of the world around the book, beyond just the book itself. That's where you really want to draw the jokes from: people's relationship with the book. What they think of when they read it. What was popular to think about it. If the comic was just me making jokes about the book, it would be kind of bland.

The comic you wrote about the three Brontë sisters seems to have really struck a nerve.

That comic got a huge response. It's in the window of a bookstore now.

Finally Anne gets a little credit for commonsense!

Anne's books are totally different from Emily's and Charlotte's. Anne's characters are horrified by what they see, while Jane Eyre is more like, "Well, I'll get used to this guy with his weird, wife-in-the-attic shenanigans. I love him!" People say that "Wuthering Heights" is a romance. It's not. It's a book about horrible people. It's more of a horror story than anything else.

It seems like messing around with historical characters might be trickier, and with your background in history I would imagine it might make you nervous.

You do sacrifice some facts for the sake of a joke. I find myself trying to circumvent any objections. One comic I did recently was about Danton and Robespierre. I drew Robespierre at Danton's trial -- which he was not. He was sick, so he wasn't there. But the comic was about their relationship, and he was responsible, so I drew him in there. I had to put at the top, "He wasn't there, I know, but anyway ..." Otherwise, inevitably, an email titled "Actually" will appear in my inbox.

You also did a series of comics based on cover illustrations that Edward Gorey did for several novels, imagining what the stories might be solely on the basis of these strange images. But I think I like your Nancy Drew series even more, possibly because the cover art for those books was so terrible and you can really go to town on it.

The progression of Nancy Drew cover art is really fascinating. In the 1930s, when they first came out, the covers showed her getting in there, into the middle of the action. She was a really strong character. Then, when they redid the covers in the '60s, Nancy becomes scared-looking, peeking around the corner with her hands on her face. She becomes much more demure and much less adventurous. It's really interesting. And then it becomes abstract, with a big Nancy head and some objects around it, fading in and out, maybe a skull.

Nancy is not a real solid character. She has a boyfriend; she likes to solve mysteries. Nancy, you can take her, stretch her and squish her, and she's still kind of the same thing. She's just a big psychopath in my comics.

Depictions of women does seem to be a theme that attracts you.

I became more aware of that because I'm a lady in the comics industry, and whether you like it or not, your name will pop-up in a lot of articles about women in comics. You kind of get this education constantly anyway, about depictions of women and women writers. You become more aware of characters who suffered badly.

Lois Lane is one of them. She's a lot like Nancy in a way. The early Lois was very elbows-out, knocking people out of the way to get the story. Then editors came in, and said, "Make Lois prettier. Lois isn't hot enough. Make sure she's the type of lady that Superman would really want to save, you know what I mean?" So, after that Lois starts to suck. She starts to be boring and whiny, saying, "Superman, why don't you marry me?" And he says [deep, exasperated voice], "I'm busy, Lois!"

But I don't have an agenda with any of the comics I do, really. I just go for being funny. When I did one about strong female characters, it was because we're all so used to these tropes of women: "She's so tough!" But she's in her underwear while shooting guns. And people say [huffily], "Well, what's wrong with being sexy?" Well, what's wrong with wearing clothes? Or proper protective gear? All these attitudes are fun to make fun of because everybody really knows better. Even the people who are defending it are secretly saying "... yeah."

Shares