For the last 30 years, the literary reputation of the working-class London neighborhoods of Spitalfields and Whitechapel has revolved around two men: Nicholas Hawksmoor and Jack the Ripper. Jack the Ripper, I trust, needs no introduction, and in recent years the architect Hawksmoor's reputation as a designer of churches has begun to rival that of his 18th century contemporary Sir Christopher Wren. But in pop culture both men have also become the focuses for a protean web of mysticism, conspiracy-mongering and alternative mythology.

For the last 30 years, the literary reputation of the working-class London neighborhoods of Spitalfields and Whitechapel has revolved around two men: Nicholas Hawksmoor and Jack the Ripper. Jack the Ripper, I trust, needs no introduction, and in recent years the architect Hawksmoor's reputation as a designer of churches has begun to rival that of his 18th century contemporary Sir Christopher Wren. But in pop culture both men have also become the focuses for a protean web of mysticism, conspiracy-mongering and alternative mythology.

The ur-texts for this addictive weirdness are "Lud Heat" (1975), a feverish book by the London poet and novelist Iain Sinclair, and an influential work of Ripperology with the lurid title "Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution" (1976), by Stephen Knight. Sinclair may be the closest thing in modern English letters to William Blake, and the delirious opening section of "Lud Heat" -- "Nicholas Hawksmoor, His Churches" -- is an intensely allusive, hallucinatory collage of poetry and prose, combining Egyptian mythology, Blake's poetry, and eight of Hawksmoor's churches into an occult map, complete with a diagram of the pentagram the churches form over central London.

Knight's book, meanwhile, is the most comprehensive formulation of the theory that the Ripper murders were committed by Sir William Withey Gull, Queen Victoria's physician, as a Masonic plot to cover up an illegitimate child fathered by Victoria's dissolute grandson, the Duke of Clarence. It's a jerry-built, "Da Vinci Code"-style construction of might-have's, what-if's and why-not's, mixing royal paranoia, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (as a putatively Masonic document, not a Jewish one), and the life of the painter Walter Sickert (who in some variations of the theory is himself the murderer).

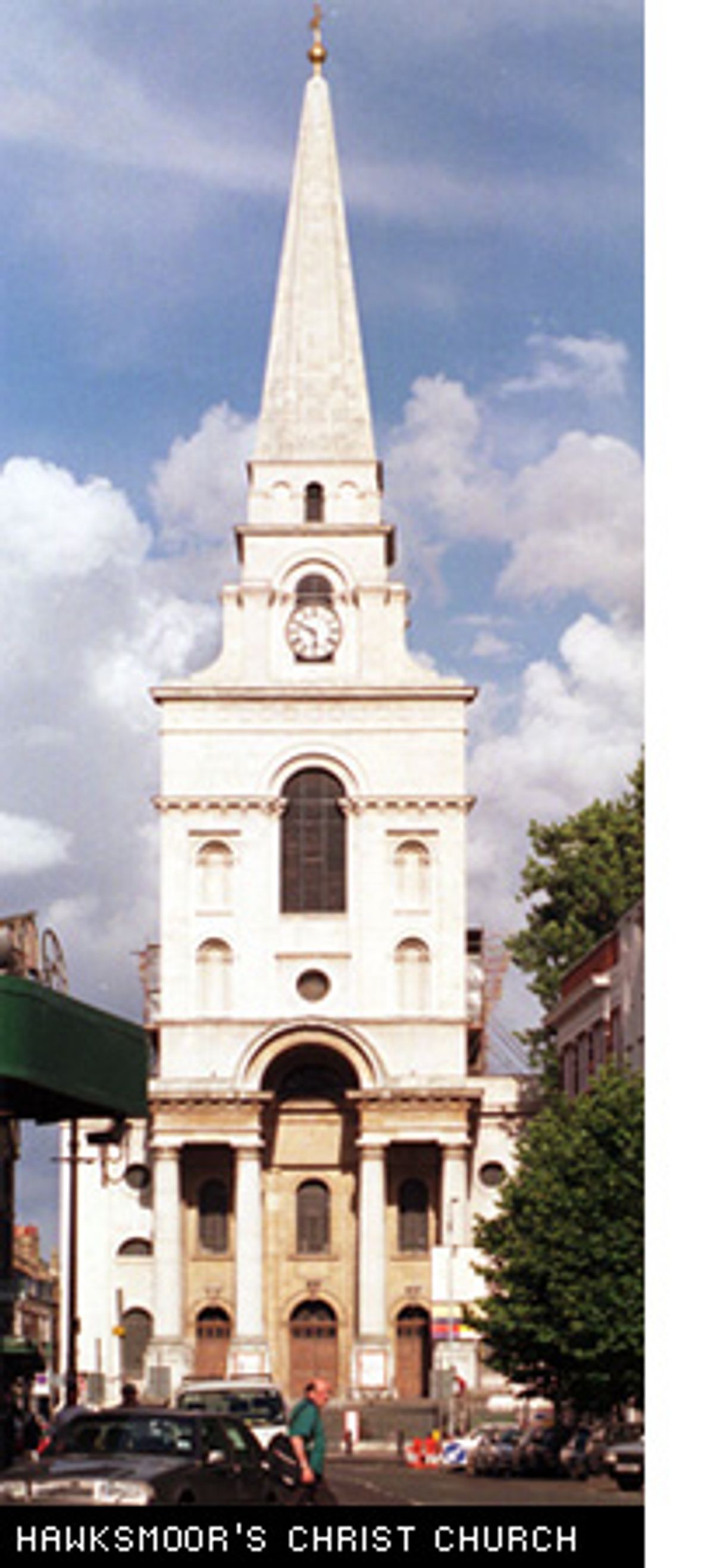

From these two springs -- occult architecture and murderous Masons -- flow several engrossing novels, all centered largely around Spitalfields and Whitechapel. In Peter Ackroyd's "Hawksmoor" (1985), which cites "Lud Heat" as a principal source -- Ackroyd being Wordsworth to Sinclair's Blake -- the 18th century architect is reimagined as a Satanist named Nicholas Dyer, layering coded pagan messages into the design of his churches, especially Christ Church, Spitalfields. (The real Hawksmoor's interest in paganism was limited to his architectural use of Egyptian pyramids and obelisks, Corinthian columns, and Persian post-and-lintel doorways.) Dyer's first-person account, a bravura imitation of robust 18th century prose, alternates with a third-person account of a series of modern murders near Dyer's churches, which are investigated by a detective named Hawksmoor. It's more macabre than conclusive, but it's a lot of fun to read.

Meanwhile the American Paul West's Ripper novel, "The Women of Whitechapel and Jack the Ripper" (1991), based largely on Knight's book, is told from the point of view of the victims and of Walter Sickert. Like all of West's novels, it's written in a dense, modernist-inflected prose, and it portrays Sickert as a weak-willed, unwilling participant in the murders. And like other recent fictions about the Ripper, it walks an uncomfortable line between feminism and sensationalism, evoking the wretched lives of Whitechapel whores with real compassion, but also showing their murders in such graphic detail it earned West the wrath of some reviewers. And there is also Sinclair's own idiosyncratic rendering of Knight, "White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings" (1987), a gorgeously written "Hawksmoor"-style narrative about the Ripper murders, alternating present and past.

But the apotheosis of creepy Whitechapel lit is Alan Moore's epic graphic novel "From Hell," originally published serially over several years in the early '90s, which combines the Hawksmoor and Ripper streams into a wild, rushing torrent, with stunningly detailed black-and-white illustrations by Eddie Campbell. I hate to overuse the word "idiosyncratic," but let's face it: Ian McEwan and Martin Amis aren't going to touch this stuff. It takes an omnivorously encyclopedic, outsider sensibility like Moore's (and Sinclair, Ackroyd and West's) to venture into this territory, and Moore's the most omnivorous of the lot, openly acknowledging his debt to Sinclair et al. in extensive notes, and dumping into the book all things London (circa 1888), including cameos by the Elephant Man, William Morris, Robert Louis Stevenson, Buffalo Bill and a young Aleister Crowley. The chapter in which Gull and his evil coachman Netley take the reader on a tour of Hawksmoor's pentagram of pagan churches takes "Lud Heat's" occult aria and turns it into a full-blown opera of classical paganism, Freemasonry and psychopathology.

In recent years, the real Spitalfields and Whitechapel have lost much of their macabre aura to upscale development and the latest influx of immigrants from Bangladesh. Spitalfields, in fact, is now also known as Banglatown, and tourists taking Ripper walking tours are likely to end up in one of the curry restaurants along Brick Lane, the titular location of Spitalfield's most recent literary representation, Monica Ali's warmhearted domestic epic of immigrant life, "Brick Lane" (2003). But then, London being what it is, compacted and labyrinthine, you can still take a five-minute walk that encompasses all of Spitalfields, from the Ripper to Hawksmoor to Monica Ali. Start in Dorset Street, where Miller's Court used to be, site of the most horrific Ripper murder, then walk east toward Hawksmoor's brooding Christ Church, towering above Commercial Street. Then round the corner up Fournier Street, past the handsome row houses built by Huguenot weavers and up to Brick Lane, where a temple stands as a palimpsest of immigrant history -- it's been a Huguenot church, a Methodist chapel, a synagogue and, since the 1970s, a mosque. Here, even in the heart of Ali's Banglatown, there's a reminder of the occult London of Sinclair, Ackroyd, West and Moore: up under the pediment of the building a vertical sundial is built into the wall, with the Latin motto Umbra sumus -- "We are shadows."

Shares