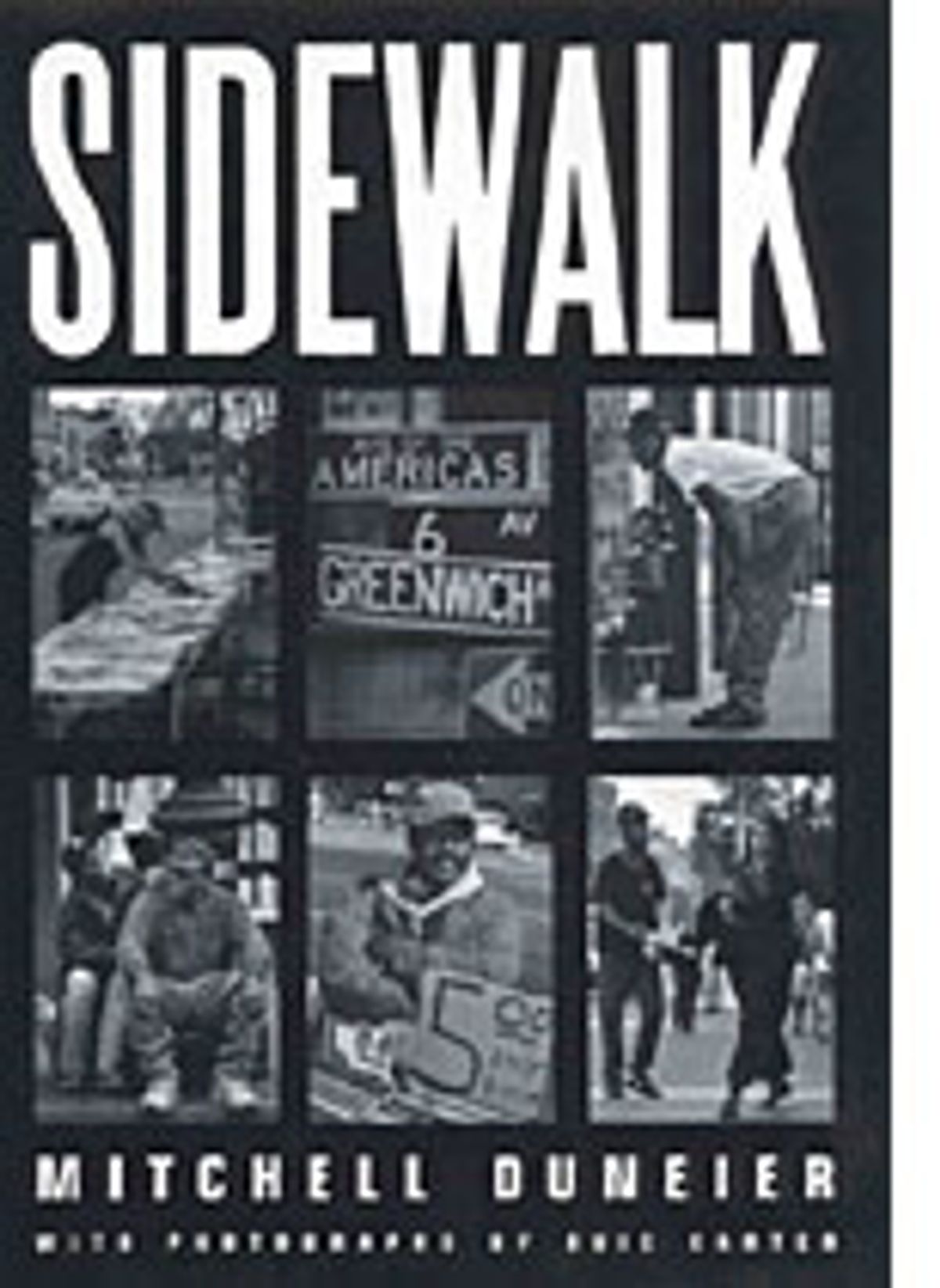

Almost at the very beginning of Mitchell Duneier's extraordinary study of the black men who sell scavenged books and magazines on the streets of New York's Greenwich Village, we learn that these men are not necessarily what they seem at first glance. Duneier, a sociologist who has taught at the University of Wisconsin and the University of California at Santa Barbara, approaches Hakim Hasan, a man he has recently met who sells "black books" from a table on Sixth Avenue, to ask him how he understands his role on the street. "I'm a public character," Hasan responds. "A what?" Duneier asks. "Have you ever read Jane Jacobs' 'The Death and Life of Great American Cities'?" Hasan answers. "You'll find it in there."

Admittedly, most of the men Duneier meets on Sixth Avenue cannot trump the visiting academic by citing chapter and verse from classic texts of social science. (There are other moments of peculiar disjunction, as when one homeless man who usually sleeps in a subway tunnel observes to Duneier that the quality of Architectural Digest has gone downhill since its purchase by Condi Nast.) But the presence of someone like Hasan, an erudite thinker who voluntarily dropped out of the formal economy to work on the street, helped Duneier understand that the world of sidewalk vending was a highly complex socioeconomic sphere with its own rules, hierarchies and sense of order. In bringing that world to his readers with tremendous humility and integrity, Duneier has written what is sure to become a contemporary classic of urban sociology.

Many observers, especially amid the "quality of life" rhetoric of Rudy Giuliani's mayoralty, are likely to view the tables of second-hand bestsellers and discarded fashion magazines -- and the men behind them -- as ugly and undesirable chaos, likely to produce crime and disorder. Over the course of the five years Duneier spent observing and even working on "the blocks" (as the vendors term their desirable stretch of Village sidewalk), he developed a different view. While several of the men he introduces to the readers of "Sidewalk" are alcoholics and drug addicts, and some (although not most) are homeless, almost all, as Duneier eloquently puts it, are trying "to live 'better' lives within the framework of their own and society's weaknesses."

After becoming friendly with Hasan -- who is neither homeless nor an addict and seems to function as Sixth Avenue's resident philosopher, mentor and informal community leader -- Duneier gradually got to know most of the street's other vendors. In addition to booksellers like Hasan, whose trade is generally aboveboard, there are magazine vendors like Marvin and Ron, a team who go through recycling bins searching out recent issues of desirable titles to sell (although the selling is legal, the scavenging technically is not). There are men who sometimes panhandle and sometimes "lay shit out" -- spread miscellaneous salvaged or stolen merchandise on the ground (which is not legal). There are table watchers (who fill in when a vendor needs to leave his table), placeholders (who stay on the street all night to ensure a vendor won't lose his spot), movers (who transport books and magazines to and from a vendor's spot) and storage providers (who can store merchandise overnight in basements or subway tunnels).

Although his sympathy is clearly with the vendors, Duneier does not flinch from recounting their failures along with their successes. He writes fascinating chapters about his observations of such frankly antisocial behavior as public urination and the harassment of female pedestrians. But what he sees in general is a dynamic economy created by a group of virtually destitute men, in which there is strong pressure to conform to societal norms. In his years on the blocks as a "participant observer," Duneier has watched homeless men become housed, addicts seek treatment and criminals turn to lawful work. He argues that any attempts to "improve" the neighborhood by purging the vendors are likely to prove counterproductive, and asks whether some arbitrary ideal of public order is worth depriving our poorest citizens of the right to pursue honest entrepreneurial activity.

Throughout his experience on the blocks (much of it working as a vendor with Marvin and Ron), Duneier remains acutely aware of the racial and social gulf between him and the men he meets. He was perceived at different times, he writes, as "a naove white man who could himself be exploited ... ; a Jew who was going to make a lot of money off the stories of people working the streets; a white writer who was trying to 'state the truth about what was going on.'"

Add to that list a noble and compassionate scholar who has made an invaluable contribution to both current social-policy debates and the cause of human understanding. As Hakim Hasan observes in the afterword Duneier asked him to write (after previously bringing Hasan to Santa Barbara to co-teach a seminar), the sociology grad student's "romanticized idea of 'the subject's voice' is one thing. The radical willingness of the social scientist to listen is quite another." Furthermore, this social scientist has displayed a radical willingness to put his money where his mouth is -- Duneier has committed to sharing the profits of "Sidewalk" with 21 of the people who appear in it.

Shares