In the 1956 comedy "The Girl Can't Help It" Jayne Mansfield drops some coins in a vending machine and receives a shiny red apple in return. For the director, Frank Tashlin, this confluence of the mechanical and the natural is (like Mansfield herself) one of the ironies of a plastic, consumerist age. Sue Hubbell likely wouldn't see any irony.

In her brief and almost mischievously provocative new book "Shrinking the Cat," Hubbell writes about the brouhaha that ensued when it became public knowledge that Monsanto had developed corn laced with Bt genes. The genes allowed the corn to grow free of a parasite that bored into it and destroyed the interior of the cob while leaving its exterior deceptively untouched. The public panicked at the thought of genetically engineered food and wondered: If the Bt genes were capable of killing bugs, well, then what did it do to people? As Hubbell writes, "All in all, the scientists in the white lab coats whom the public was calling Dr. Frankensteins were startled about the reaction to the Bt-corn story. Most of them had their own doubts about genetic engineering, had their own questions to ask, but they knew that inserting a Bt gene into corn was not nearly as big a deal as creating corn in the first place. That was a very big deal."

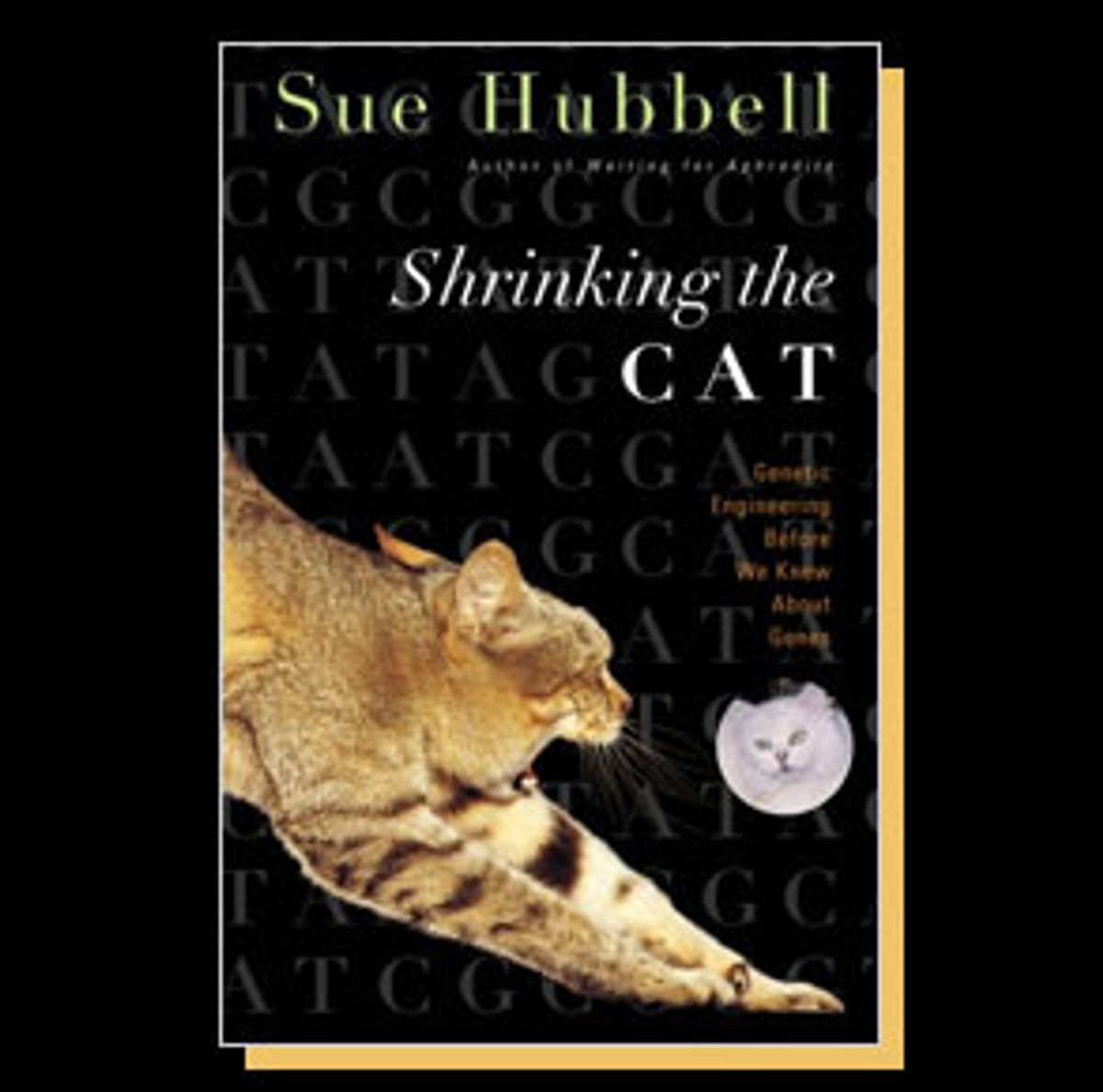

It's Hubbell's intent in "Shrinking the Cat" to defuse the uproar over genetic engineering by demonstrating, as her subtitle says, that even before humanity knew there were genes, we were already fiddling around with genetics. To make her point, she focuses on four objects so common that most of us imagine they've always been as they now are: corn, silkworms, cats and apples. It's a homey little list and that familiarity is part of Hubbell's cheeky deviousness. After all, if she can demonstrate to us that these everyday things have been tinkered with, she can then dispel our visions of mad scientists messing with the laws of nature deep in the bowels of their laboratories -- and then maybe we'll be able to look less fearfully on genetic engineering. One irony that Hubbell must have appreciated is that over the recent Thanksgiving weekend, when the story broke about the successful cloning of human embryos at Harvard, at least some of the people who expressed horror had a few days earlier partaken of an all-white-meat turkey -- another example of genetic mucking about.

Hubbell doesn't exactly tackle the big questions here. Few of us would feel that the changes that developed in cats as they became domesticated, or the recombinations of apples that have produced the most popular varieties, have the same import as the possibility of altering the biological (and maybe eventually the psychological) makeup of humans. That's because, Hubbell would argue, our fear is strongest when we feel that it's our essence that's being tampered with. Human beings, we'd like to believe, present an exceptional case; we're special, different.

Hubbell devotes part of her introduction to a discussion of the hubris that put human beings at the top of lists of the smartest animals. Such lists, Hubbell points out, are hardly objective because they are devised by humans. To illustrate, she offers a story of her late, beloved dog, Tazzie the Good. (Hubbell has some odd ideas about pet names. Her cat, a male, is named Black Edith Kitty; he's a boy with a girl's name, she explains, just like in "A Boy Named Sue.") Every night that she took Tazzie for a walk in her Washington neighborhood, Tazzie unfailingly found a bone.

"Tazzie," Hubbell writes, "was sapient in a dog's world, many aspects of which are not mine. Her world and mine overlapped at certain points -- we were companions -- but our skills, our intelligences, were for our own ways of life, not each other's. And those ways of life were determined by different biologies, different configurations of our DNA." She's right. Hubbell could no more have found those bones than Tazzie could have written this book. Her point is that neither she nor her pooch is expected to fulfill the tasks. Still, it's hard for us to shake our belief in human exceptionalism, hard not to ask, "Where are the canine Shakespeares?"

There's not much that even Hubbell's reason and rationality can do to change our belief in our own exceptional nature, and that belief leads us view the occasions when human beings have interfered with the essences of other human beings with particular horror. I'm not just thinking of the obvious examples, such the Nazi medical experiments, but also of some of the darkest episodes in this nation's history, like the 1930s "mental hygiene" movement which tried to eradicate criminal or subversive behavior by lobotomy. (A brief history of that movement can be found in "Shadowland," William Arnold's investigative biography of the actress Frances Farmer.) Only the doctrinaire would want to stand in the way of our acquiring the ability to rid humanity of the genes that cause cancer or heart disease (or whatever it is that causes some people to whistle in bookstores). But just as Tazzie knew where to find those bones, perhaps we know human character well enough to fear that it wouldn't stop there. And that knowledge is lurking at the back of Hubbell's cautiously optimistic conclusion.

Furthermore, there is something about Hubbell's matter-of-factness that both calms you and gives you the twitches. She knows damn well she's toying with us when she says, "What's the big deal about genetic engineering? Let me tell you how they make Golden Delicious apples." There's a grin lurking somewhere in the back of her reasonable prose, with its peculiar mixture of formality and comfort (and its accessibility to those of us who worry we'd be lost in any discussion of science). She knows she's making us uneasy, and she can't help enjoying it.

Hubbell ends by saying this is "a hopeful time in which to live" but there's pessimism lurking in her demurral. She insists that until we can reach a greater understanding of how genetics works, "including an understanding of how forms of life are related to one another, we'll continue to suffer the unintended consequences of alterations." But, she has demonstrated, those alterations are unavoidable, the consequence of any living being's interaction with another species. "Shrinking the Cat" is a vision of nature as a Waring blender presided over by a cosmic mixmaster who occasionally lets us mortals seize the controls. If we proceed with caution, there may be a really neat smoothie at the end of it, instead of toxic muck.

Shares