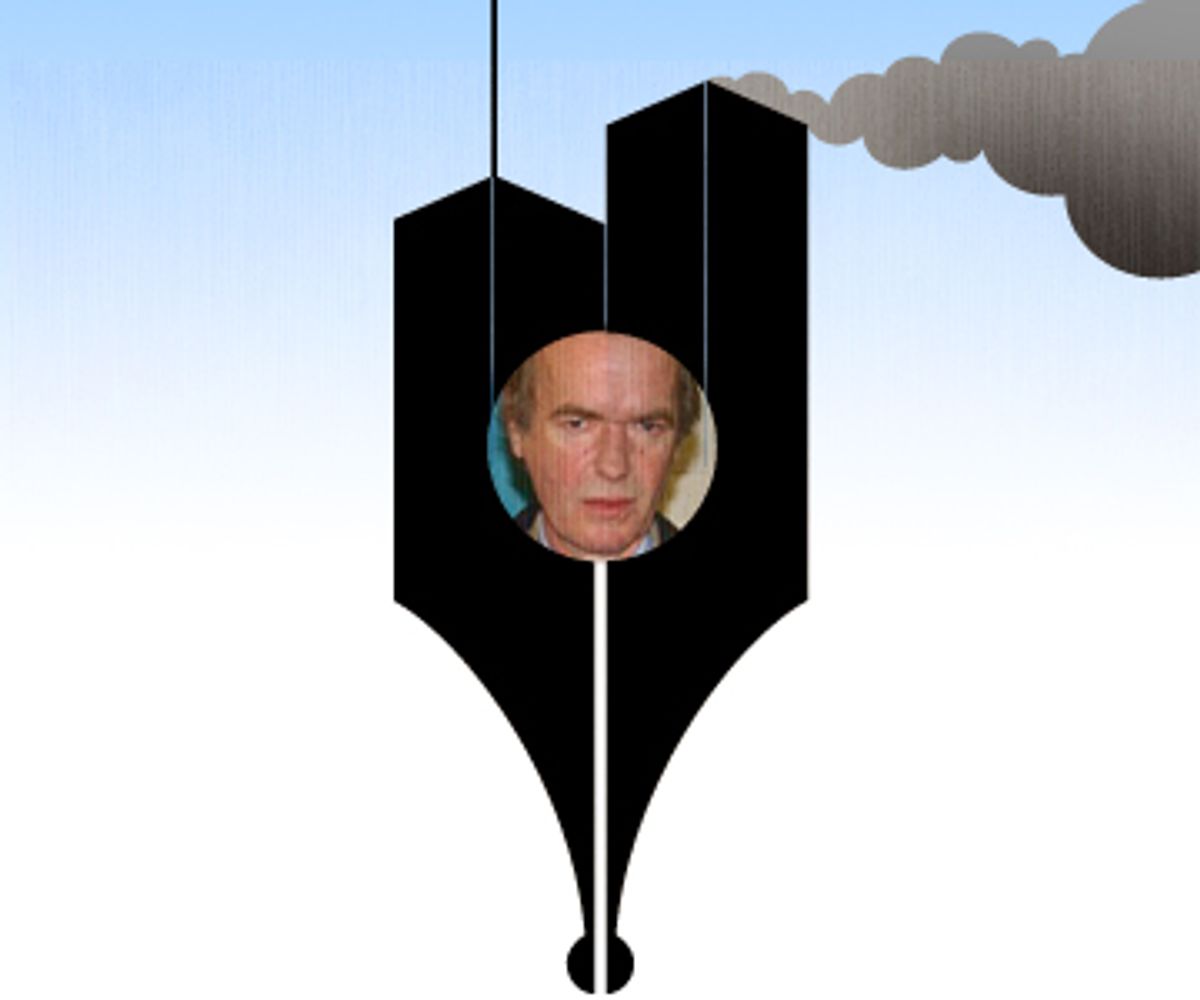

Here is how Martin Amis, in the long essay "Terror and Boredom: The Dependent Mind," at the center of his new collection of writings on Sept. 11, describes Donald Rumsfeld's demeanor on television during the early days of the Iraq invasion: "He looked as though he had just worked his way through a snowball of cocaine. 'Stuff happens,' he said when asked about the looting of the Mesopotamian heritage in Baghdad -- the remark of a man not just corrupted but floridly vulgarized by power." And here is how Amis experienced Tony Blair's visit to the Bush White House: "The whole place fizzes with zero tolerance, with the prideful tension and frigidity of high protocol. Its peculiarly American flavor is evident in the sustained choreography and the dread of the spontaneous. This does remind you of something: a film set."

In Amis' work, lines like these are the franchise. They're the reason you buy a ticket and get on the ride. Amis himself admits as much; discussing his fiction in an interview with the Paris Review, he dismissed "story, plot, characterization, psychological insight and form" as merely "secondary interests" compared to a novelist's prose, little more than the apparatus on which to hang some bitchin' sentences. So it hardly seems an insult to say that his specialty is not substance, but style.

Nevertheless, Amis has never been content with the boundaries of his own aptitudes. Earlier in his career, when seeking subject matter with which to demonstrate his seriousness, he often settled on the topic of nuclear weapons. Lately, for obvious reasons, he has switched to Islamist terrorism. Clearly, his taste in issues runs toward the apocalyptic.

The pieces collected in "The Second Plane: September 11: Terror and Boredom" ruminate on a few aspects of the current conflict between East and West, but Amis' main interest is Islamism, the militant ideology that motivated the terrorists who attacked the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and, in 2005, the London transit system, among other targets. His pronouncements on Islamism have gotten him into trouble in his native England, when he chummily confided, in an interview with the Times of London, that he sometimes feels the urge to impose various civil harassments on "the Muslim community" -- strip searches, deportation, "discriminatory stuff" -- until they "get their house in order" by "getting tough with their children."

It was a stupid remark -- beyond the manifest stereotyping, why should Muslim parents be any more effective in "getting tough" with their young adult children than Western ones? -- as Amis himself soon conceded. Still, he was excoriated in the press by the Marxist literary critic Terry Eagleton and various other leftist commentators. He's been called a racist and an Islamophobe, to which he's retorted that he is instead an "Islamismophobe," hating and fearing only the politically militant manifestation of the religion. Fair enough, and as Amis has pointed out, the left ought to be sensitive to the distinction, since Islamism itself is an ideology that is "racist, misogynist, homophobic, totalitarian, inquisitional, imperialist and genocidal."

In the last essay in this collection Amis tells of an appearance he made on the BBC's "interactive discussion show" "Question Time," in which he argued that instead of galumphing into the debacle of the Iraq war, "the West should have spent the last five years in the construction of a democratic and pluralistic model in Afghanistan." His point was reasonable, if naively unrealistic. (The world's great powers have never been interested enough in Afghanistan -- whose only geopolitical significance is its location -- to invest that much time, attention and money in it.) A young woman in the audience stood up, speaking "in a voice near-tearful with passionate self-righteousness, saying that it was the Americans who had armed the Islamists in Afghanistan, and that therefore the U.S., in its response to Sept. 11, 'should be dropping bombs on themselves!'"

Perhaps there's a little comfort in knowing that the geopolitical conversation broadcast on British television is nearly as idiotic as that in the U.S., albeit from the opposite end of the political spectrum. It might also explain why Amis feels that his own contributions to the discussion, an assortment of articles, Op-Eds and stories previously published in various newspapers and magazines, merit publication as a book. If "They ought to be bombing themselves" passes for a trenchant critique of American foreign policy in the U.K., then the essays and fiction in "The Second Plane" probably do seem brilliant by comparison.

In truth, though, there's not much insight or thoughtfulness in this book, which makes it a pretty fair example of the myopic Western attitudes that helped create the problem it describes. There's lots of fulmination, though, fulmination of the very highest order. Islamism is "an ideology which, in its most millennial form, conjures up the image of an abattoir within a madhouse." Sayyid Qutb, one of the ideology's founding theorists, writes with "a leaden-witted circularity. The emptiness, the mere iteration, at the heart of his philosophy is steadily colonized by a vast entanglement of bitternesses." The possibility of Qutb's target audience recognizing this is slim because "no doubt the impulse toward rational inquiry is by now very weak in the rank and file of the Muslim male."

You might have noticed a little slippage there in the targeting of Amis' invective. I am sure that even Terry Eagleton -- no slouch in the hysterical denunciation department himself -- would refuse to defend the Taliban. The argument raised by Amis' more reasonable critics, the fact he can't seem to hold onto despite his talk of "Islamismophobia," is that Islamism and Islam are not one and the same.Islamism is a fringe movement in the Muslim world, one that holds little real appeal for the vast majority of shopkeepers and small-businessmen who make up the stable political classes of Arab and Muslim nations. Depending on how disgusted any of them might be with the West at a given moment, they might claim to approve of, say, the suicide bombing that blew a hole in the USS Cole in Yemen in 2000. But you can also find plenty of Americans who, with a few beers in them, will announce that we ought to "nuke the whole Middle East." That doesn't mean the U.S. is in serious danger of adopting such a course. Even the young woman who stood up to denounce Amis on "Question Time" doesn't really want to see the U.S. bomb itself.

It's true that the world that Islamist terrorists say they want to create -- the restoration of "the Caliphate" under a system of sharia law and the eventual (willing or forced) conversion of the entire planet to fundamentalist Islam -- is a ghastly one, "a world with no games, no arts, and no women, where the sole entertainment is the public execution," as Amis intones. But this vision is even less viable than a pipe dream. The threat these terrorists pose is not that they'll succeed -- as Gilles Kepel has pointed out, close study of the recent political history of the Middle East reveals that Islamists have never been able to command substantive and lasting support outside of Iran, and even there it gets wobbly. The danger is that in their failure they will lash out at their enemies with ever more lethal ingenuity.

Still, even if Islamists had the ability to blow up airplanes and train stations every month, they couldn't conquer the West. What they can do is provoke the West to behave in ways that drive Muslim supporters to their cause or to causes like it, and this they have accomplished with impressive economy. The fall of the twin towers wasn't al-Qaida's greatest achievement; Abu Ghraib was. It's been seven years since the Islamists' last and only effective attack on American civilians, and they are still reaping the benefits of it in the hubris and incompetence of the West's reaction. Given this reality, which even Amis seems to acknowledge at times, ranting on about the nightmare scenario of an Islamist world government seems beside the point, if not downright unhelpful.

The pieces in "The Second Plane" are arranged chronologically, and Amis has for the most part shown admirable restraint in not updating them. They are like a series of time capsules tracing the evolution of an intelligent but spottily informed Westerner's response to the event. So, the first essay, written on Sept. 18, 2001, describes United Airlines Flight 175 as aimed at America's "innocence," which is exactly how Americans experienced it. (Amis was living with his American wife in Long Island, N.Y., at the time.) The hijackers, of course, saw America as arrogant, not innocent, not merely confident that her sins against the Muslim world would go unpunished, but positively reveling in them. It quite likely never occurred to them that most of the people they killed -- and the millions more they terrorized -- had never before given Islam a second thought and were completely oblivious to their grievances.

Similarly, although Amis has nothing but contempt for George W. Bush (and for religious believers in general, for that matter), he does share the president's conviction that what really motivates Islamist terrorists is a loathing for the West and the hankering to destroy it. So the passenger jets used in the Sept. 11 attacks have to be symbols of "indigenous mobility and zest, and of the galaxy of glittering destinations" because that's what they mean to us, rather than, say, the ill-gotten booty in a rigged contest for global dominance. In other words: They hate our freedoms.

Without a doubt, Islamists do work themselves up into a state of anti-Americanism by contemplating the "depravity" of Western life: the materialism, the sexual promiscuity, the "looseness" of our women, the indulgence in drugs and alcohol and the general lack of moral fiber. That's what makes fundamentalism so modern and not the "late-medieval" phenomenon that Amis mistakes it for. It is an allergic reaction to modernity that wouldn't exist without global capitalism and consumerism to provoke it. The people who embrace it may be viciously deluded, but they really do believe that they are defending the last vestiges of decency against a tidal onslaught of smut and greed and cynicism. They aren't nihilists, in love with death, as Amis claims, but young men, drunk on a hallucinatory, quasi-tribal code of honor, who have been convinced that they are giving their lives for a cause greater than themselves. We've seen their likes, if not their tactics, before. Like all killers, they need to dehumanize the people they murder in order to convince themselves that they're in the right.

Amis has read a few books on his subject, most notably Paul Berman's "Terror and Liberalism" and Bernard Lewis' "What Went Wrong: Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response," neither without merit but hardly enough to give a full picture. To this, he's added a dash of Sam Harris' "The End of Faith," a diatribe against religion that comes across as bombastic even if you happen to agree with it. Thus fortified, Amis sallies forth, to slash left and right at monsters that nobody, really, is prepared to defend, clipping a few innocent bystanders in the process. "We are not hearing from moderate Islam," he says stoutly. Mostly this is because he's not listening, but then neither is anyone else. As Eboo Patel, executive director of the Interfaith Youth Core in Chicago, related during a recent radio appearance, "I will get up and give a talk to 250 people, and people will stand up and say, 'Where are the moderate Muslims?' I want to say, well, you know I've just spoken for sixty minutes and now you pretend you haven't heard me."

How can Sufis and mild-mannered suburban imams compete against the likes of Mohammed Atta when it comes to galvanizing a man's (and the media's) attention? Amis clearly finds him fascinating, for not entirely clinical reasons. Atta, at least as Amis imagines him in a short story that originally appeared in the New Yorker, was possessed not by religious fervor, but by a titanic disgust with the world, particularly with the trash and tedium of the West, but also generally, with the mortifications and degradations of the flesh. In that, he's not so very different from a host of Amis characters, from the misanthropic title character of "Money," to Nicola Six in "London Fields," a woman whose sexual self-loathing drives her to suicide, to Richard Tull, the poisonously envious failed writer in "The Information."

Besides the Atta story, Amis started and then abandoned a novella about a fictional Islamist, so he's been thinking a lot about what goes on in the minds of such men. He believes that they view contemporary Western life as a garish carnival of empty sex, tasteless consumption and mindless violence practiced by vapid, amoral narcissists with two-second attention spans. In short, they see it pretty much as the average Martin Amis novel does, but without quite so much despair because the terrorists, at least, believe that heaven lies beyond martyrdom.

I expect this recognition gave Amis a turn -- I know it would me -- that is, if the similarity has occurred to him at all. Whether consciously acknowledged or not, the likeness explains why an author might choose to write so much on a particular topic without attempting to learn much about it. The underlying impulse could well be not to figure out how the terrorist mind works but, rather, to insist that it doesn't really work at all, that it contains nothing but howling chaos, humiliation and paranoia, incapable of love or reason, a "nullity" in which "violence is all that is there" -- in short, that a terrorist isn't even human. This, alas, isn't true; humanity is full of very unpleasant surprises, and manages to go on surprising us with them no matter how well we think we know our history.

For Martin Amis, one of the nastier discoveries is that the people who most share his revulsion toward contemporary Western life also happen to be mass-murdering religious fanatics. Well, he should take heart; at least he'll always be able to write circles around them.

Shares