"What's this, Daddy?" my 6-year-old son asked me one morning, as we were mucking about in the backyard. He was holding a rusted, mud-and-clay spattered hunk of cast iron, heavy enough that he could barely hoist it waist-high with both hands.

I recognized it as the head of a mattock. But I told him it had to be a magical artifact dating back to an ancient, lost civilization that had flourished in what is now called "Berkeley" thousands upon thousands of years ago.

His eyes sparkled. It wasn't that he believed me. I'm not trustworthy on these matters. But a 6-year-old digging in the mud doesn't need much encouragement. Suddenly, his latent paleo-archeological inclinations blossomed. He found a little paintbrush to wipe the dust off half-buried bricks. He began a running commentary: A salamander under a rock became a Great Snake Demon. A broken hoe blade -- a fragment of the shield of the mighty warrior MegaMon.

Ancient civilizations are seductive. Lost ancient civilizations are better. Lost ancient civilizations that thrived in a time of magic and mystery when gods walked upon the earth are the bee's knees. I know -- I've spent most of my life looking for them. When I was a teenager, the myths of Greece and Rome and the sagas of Northern Europe delivered them to me. Later, I made an extended stay in the Far East, where the antiquity was layered so thick one breathed it in with every gasp. Today, as a parent and wage slave, I get them via the fantasy tomes teeming in every bookstore.

There is no shortage of fantastical worlds to plunge into, but it is not always a satisfying submersion. So much of what is available is so, well, unimaginative. Even excluding what is just plainly bad -- Extruded Fantasy Product, as the aficionados like to call it, from the likes of Robert Jordan or David Eddings or a host of even less talented imitators -- we're still left with endless retreads of the same basic story lines. If it isn't yet another reworking of tired medieval chivalry tropes (Hey, I adore the work of George R.R. Martin as much as anyone on this planet, but even I get tired of page after page describing the household sigils of this noble family or that, or what the knights were wearing just before they ran off to joust), then it's another plague of goddam elves. (So tall! So thin! So tragic! Like a race of supermodels.)

Watching my son evoke complexity from slivers of stone and rusted farming implements, teasing out a narrative that, though fundamentally incomplete, was still beguiling, helped me get a better grasp on what I find exciting. Successful fantasy does not require magic swords, or the triumphant overthrow of whatever Evil Dark Lord of Black Shadow Midnight Murk is currently torturing the poor denizens of Happiland. It doesn't even require a subplot involving a teenage boy (or increasingly often, girl) who becomes a Man (or Woman) while on a dire quest to find (or destroy) the Holy Trinket.

Give me, instead, the evocation of a rich, complex and yet ultimately unknowable other world, with a compelling suggestion of intricate history and mythology and lore. Give me mystery amid the grand narrative. There's no need to spell it all out; no prefaces, please, elucidating the history of Middle Earth as if to students in a lecture hall. Instead, give me a world in which every sea hides a crumbled Atlantis, every ruin has a tale to tell, every mattock blade is a silent legacy of struggles unknown.

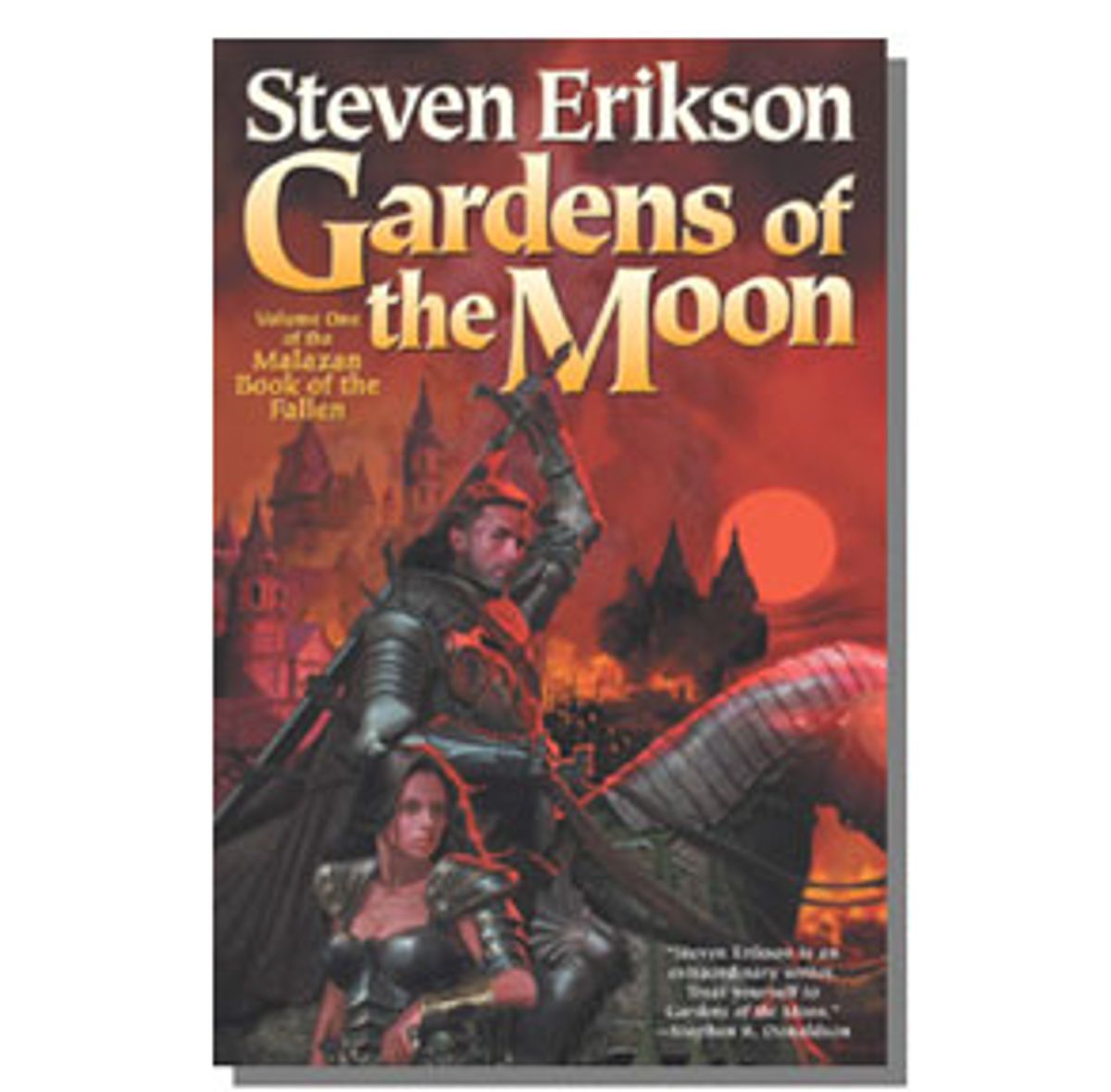

Give me, in other words, the fantasy work of Steven Erikson. A newcomer to the United States fantasy market, Erikson is a Canadian by birth who lives in the U.K. and has already finished five volumes of "Tales of the Malazan Book of the Fallen," which is purported to be a 10-volume series. The first installment, "Gardens of the Moon," has just been released in the U.S. by Tor Books. I liked it so much that, as if compelled by nefarious powers beyond my control, I had to order the next four online and devour them all in one self-indulgent but extraordinarily enjoyable marathon.

Erikson is a master of lost and forgotten epochs, a weaver of ancient epics on a scale that would approach absurdity if it wasn't so much fun. His time span ranges over hundreds of thousands of years. Races (both human and nonhuman), cultures, empires and even gods rise and fall. Vast struggles range across multiple continents and dimensions of time and space. There are so many fragments of myth, so many hints of back-story unending, and so little explained, that it is all the reader can do to comprehend what is going on, to hang on to the narrative as if clinging by one hand to the underbelly of a flying dragon. (And yes, there are dragons, and magic swords, and quests, too. But not a whole lot of teenagers.)

Erikson has trained as an archaeologist and anthropologist, and in one interview noted that he has extensive experience doing fieldwork at sites in Canada whose relics date back 8,000 or 9,000 years. So it is no accident that ruins abound in his work. It's no accident that he's obsessed with the passage of time, with epochs and eras. There are races in his universe that wield glacial ice ages as weapons; that are themselves living fossils; that seek the bones of their ancestors so as to resurrect their tribal gods; that are at war with the gods.

Each novel in the series so far, though many involve continuing characters and plots, can stand alone, and explores its own internal dynamic of history and myth. A favorite technique of Erikson's is to begin one of his tales with an event in the ancient past, some clash between gods and Elder Races and alien interlopers that, by the time the main narrative has begun, has receded beyond mortal memory.

Each novel, then, is a chance to watch myth-creation in action, to see how choices made at the dawn of time play out across the ebb and flow of civilization and empire. Languages change, gods get bored or die, entire races vanish from the face of the planet, and the truth becomes twisted. In more than one book, races and cultures exist and evolve for thousands of years with only the haziest knowledge of their own beginnings. One nation even ends up getting its own creation myth completely wrong: a tragedy with disastrous consequences. One character, Icarium, "a mixed blood Jaghut wanderer" who pops up from time to time wreaking havoc, and who has lived for eons, suffers from his own devastating memory loss, trapped in an eternal search for the truth of his own identity. Everyone, it seems, must at one point or another struggle with the immensity of this world's past.

War is a constant -- from continent to continent, century upon century. Erikson's universe is a violent one, Gothic in intensity, without clear demarcation between good and evil. It's perhaps more like the real world, then, than most fantasy, which so clearly differentiates between light and dark. Not the kind of story I would read to my son before bed -- death and pain abound, along with magic and wonder.

I won't attempt to describe the plot. It would be cheating. Readers of "Gardens of the Moon" are confronted with a world where very little is explained as it happens -- like the characters in the story, we have to piece together what is going on from cryptic utterances by gods and warlocks and seers and the fragmentary record left behind by the detritus of previous empires. To leapfrog this process by making sense of it would defeat the purpose of the author.

In the online nooks and crannies where fantasy readers discuss their addictions, Erikson's unwillingness to lay it all out clearly has led to pushback, to complaints that he is too obscure, too complex, too obtuse. And I concede that there were moments when I felt lost, when even constant trips to the glossary and who's-who left me confused. There are destabilizing points where one realizes that from continent to continent and race to race, the names, attributes and powers of, for example, various gods, seem to be in flux. Contradictions abound.

As I pushed deeper into the series I found myself more and more willing to trust Erikson, to enjoy the process of unfolding clarity that reveals itself in each volume. I also began to realize that the ambiguity reflected a little reality in the fantasy. Gods are always messing with mortals in Erikson's work, but the mortals also, by their patterns of belief, create their own gods, their own greater powers. Everything is flux. Men and women ascend to godhood; gods die or lose their powers as the cultures that revered them decline; cultures that go sour generate their own evil. It's a messy, complicated business, and there are no easy answers, or clear heroes. But there is a sense of familiarity, even though there is not a knight to be found in this magic land. Erikson's books are fantasy for gothic grown-ups, but its war-torn world of constant upheaval reminds one an awful lot of our own.

Shares