"I take serious offense to the RNC being in my fuckin' city; it's really pissing me off. It's the same scumbags who don't live anywhere near you, but are still going to organize a force to stop you from having an abortion -- because they care about you. The same people want to feel our pain over 9/11, but they don't realize that we're in a completely different place. The people who actually experienced it have no connection to these people coming in. They didn't experience it, they don't understand what we feel, and they don't understand us. It's just manipulation."

-- Brooklyn, N.Y., rapper El-P

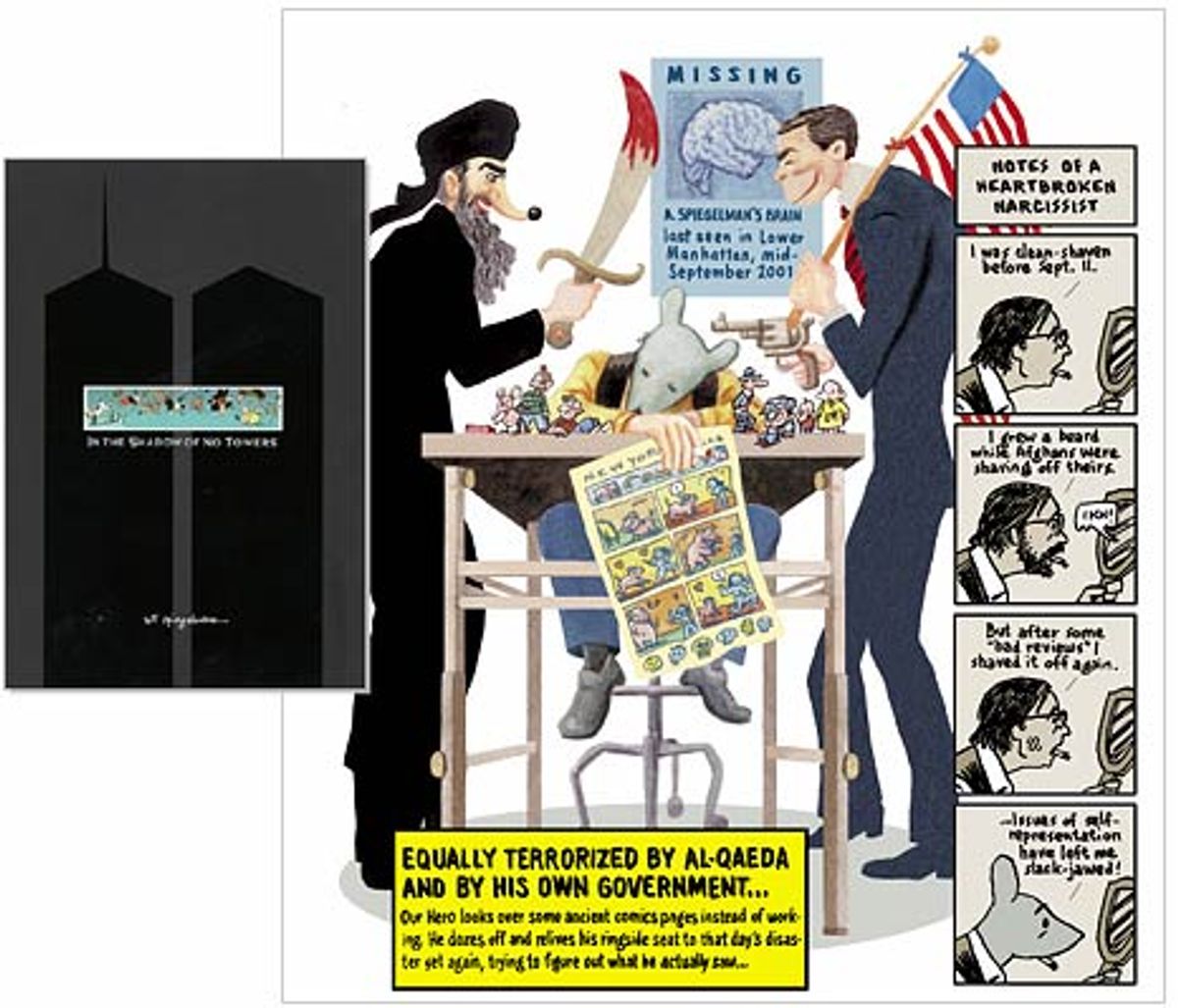

Art Spiegelman's works, especially the groundbreaking Holocaust comic "Maus," have always been as much about phenomena occurring outside his vertiginous comic strip frames as about the events within them. This is because the world around the famed comix lifer has always seemed on the verge of annihilation -- as he confesses more than once in his sprawling, sharply satirical "In the Shadow of No Towers," a collection of strips built by Spiegelman over the last three years and finally published by Pantheon Books just before the third anniversary of 9/11.

In his foreword to "No Towers," Spiegelman writes that the book's gorgeous "single-page units," printed on 42 pages of heavy card stock and designed to resemble the Sunday newspaper comics panels of a bygone era, "corresponded to my existential conviction that I might not live long enough to see them published." His parents' ordeal in Auschwitz at the hands of the Nazis, he goes on, taught him to "always keep [his] bags packed." Spiegelman freely admits that the psychic terrors of 9/11 corresponded to a deep-seated "self-inflicted" trauma, a fervent belief that Armageddon -- both the religious conflict and the Bruce Willis movie -- was, as the Rolling Stones sang in "Gimme Shelter," "just a shot away."

This kind of unrelenting dread has kept artists of all kinds in full sublimation mode since the invention of the cave drawing, and has provided human culture with no shortage of standout works. But this latent fear has also invigorated the capitalist schadenfreude of everyone from Fox News to Manhattan street merchants to the Bush administration, not to mention the supposedly liberal New York publications that avoided Spiegelman's post-9/11 rants like they were undocumented Arab immigrants. And Spiegelman, always the astute cultural critic, knows this better than anyone.

Indeed, his July-August 2003 installment of the "No Towers" series dedicates itself to the profit others have reaped off the backs of citizens thrown into chaos by a national tragedy. In one of two vertical strips (as with everything Spiegelman, the arrangement and construction of his comics deviate from standard convention whenever possible), one of the artist's doppelgangers holds up a garish tourist trap clock emblazoned with the twin towers, a looming American eagle, FDNY figurines and a United States flag, confessing that he was an eyewitness and even a participant in "the bombardment of kitsch" that hit the U.S. after 9/11 like an X-rated Xtina video on Kazaa.

In the second strip, the same clock blows up like a bomb in Spiegelman's face, as cowboy boots branded with dollar signs fall from the sky on a fleeing populace filled with cartoon legends like Annie, Wimpy, Hapless Hooligan (who repeatedly serves, as do the meek mice from "Maus," as a Spiegelman alter ego), Charlie Brown and many more. Even this summer's Republican National Convention -- the capitalization on misfortune to end all capitalizations on misfortune -- is identified by the author as an example of tragedy "transformed into travesty."

This must-have collection of hard-hitting, self-deprecating strips on life during wartime was ignored during its creation by the very publications that made Spiegelman a big name in New York literary and artistic circles: the New York Times, the New York Review of Books and the New Yorker (which has both commissioned Spiegelman for cover art and employed his wife, Françoise Mouly, as an art editor). As he admits in the foreword, "Outside of the left-leaning alternative press, mainstream publications that have actively solicited work from me ... fled when I offered these pages or excerpts from the series." In fact, the only mainstream homes for his controversial work were found in the countries -- Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands -- that were lambasted by Donald Rumsfeld and George W. Bush as "old Europe" and derided by the American media.

In a sense, this neglect helped push the work further. "The feelings of dislocation reflected in these 'No Towers' pages," Spiegelman writes, "arose in part from the lack of outcry against the outrages [of the Bush administration] while they were being committed." Now, in the most heated political season of recent generations, those who once spurned Spiegelman's work have recovered their cojones, and "No Towers" is something of a hot commodity.

New Yorkers like rapper El-P, quoted above, are justifiably sick and tired of facile 9/11 sympathies that turn out to be marketing gimmicks. But no one's going to accuse Spiegelman of cashing in on the tragedy's third anniversary, and not just because he is a New York lifer who has consistently raged against the machines of oppression and manipulation since his days editing the seminal '80s graphic mag Raw. The Pantheon press kit is now packed with fawning headlines from the publications that showed him the door two years ago, but Spiegelman can only control what ends up on the spectacular colored pages that set "In the Shadow of No Towers" apart from every other 9/11 interrogation.

As Spiegelman notes in "No Towers" while fleeing the crumbling World Trade Center and encountering a giant billboard for Arnold Schwarzenegger's fireman-revenge drama "Collateral Damage," irony is not dead. Neither is the idea that art can sometimes transcend the pleasure, pain and callous commerce of the world that generates it. Spiegelman's highly personal exploration of the horrors of 9/11 and how they nearly destroyed him (even as they were being perverted by the "Architects of Armageddon," as he calls Bush, Cheney and Rumsfeld, into a blank check for imperial aggression) offers a more powerful criticism of postmodern America's state of affairs than most of those found in this season's Bush-bashing titles. Even better, this lavishly produced, eye-popping collection costs only $20 -- a bargain for a work of comics art this sophisticated (and likely to become a collector's item).

If anything, the fact that the American intelligentsia finally seems ready to admit that Spiegelman was speaking truth to power in the dark years of 2002 and 2003 ought to make us sleep a little better at night -- at least until, as Spiegelman explains in "No Towers," the sky starts falling again and the duct tape market catches fire.

Shares