Since the morning of Nov. 3, that old saying about being doomed to repeat history has never felt so urgent. Nary a whisper about the past can float by without those of us still reeling over the "moral values" vote wondering what earlier times have to tell us about our own. Some draw parallels to the profound societal divisions of the Vietnam era; others audaciously compare our age to the Third Reich. A flurry of new books about the Founding Fathers argue that the rise of George W. Bush and his army of conservative Christians was foretold by the signing of the Declaration of Independence. But none of those go back far enough. If we really want to know the history we've been doomed to repeat, we have to return 900 years, to medieval Paris.

As James Burge eloquently argues in his new biography of the Middle Ages' most famous couple, "Heloise and Abelard," the 12th century was the beginning of the modern age. The term "Middle Ages" is something of a misnomer; this period was "the beginning of something, not the middle." The word "modern," in fact, came into use at this time. Humanism, the corporation and even the Electoral College have their roots in medieval Europe. Scholarship and philosophy were becoming popular, long before the Renaissance. Amid a population boom and a major cultural shift, the 12th century ancestors of today's conservatives and liberals were sparring over politics, religion and sex.

Of course, medieval society wasn't quite the same as contemporary Western culture; for one thing, it was profoundly religious, and the "liberals" of the day weren't interested in secularism so much as a more tolerant theocracy. Although church and state were separate, the 12th century Christian church (not yet divided into Catholic and Protestant) was itself a government, in some ways more powerful than the king, and it was for the leadership of religious society and the future of Christianity that these conservatives and liberals were fighting.

While the era's worldview was dramatically different from our own, its political battles were strikingly similar. The reform movement, which you might call the religious right of its day, believed that not only sex but also sexual fantasies were inherently evil, and enforced chastity was high on its agenda. It saw the prostitution, fornication and even the women's fashion of pointy shoes as evidence of a corrupt society. Burge, a documentary filmmaker for the BBC and Discovery Channel, puts the controversial love story of Abelard and Heloise squarely in the middle of this movement, and the result is a riveting study of faith and sex, set against a conservative uprising so familiar it will make you gasp with recognition.

The impetus for Burge's biography wasn't the "moral values" vote, however; it was a discovery made in 1980 by a scholar in New Zealand with the marvelous name of Constant Mews. In the midst of a 15th century style book on letter writing, Mews discovered 113 never-before-seen letters between Abelard and Heloise. The bulk of our knowledge of the couple previously rested on just eight letters they wrote to each other after they had been separated; the new letters were written during the affair. With the slow creep of time that marks scholarly advancement, the impact of the new letters is just starting to be felt, and Burge's is the first biography to draw upon them. Though they supply fresh texture and detail to the couple's daily life -- the two of them argue, woo each other, make up -- the letters don't change the basic story. Burge's greater contribution is the cultural context he gives to the affair, and the meld of philosophy and history he employs to explain their actions.

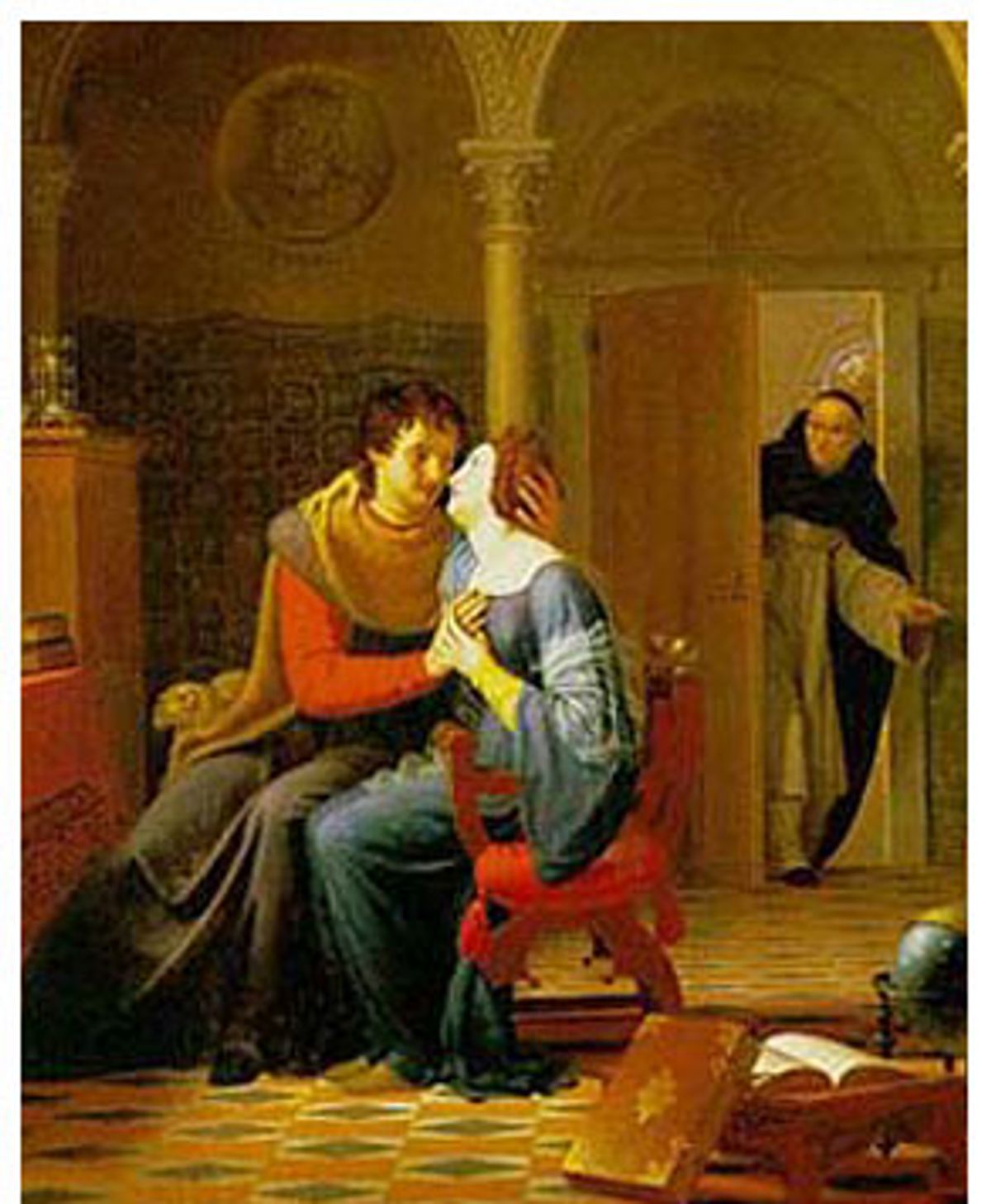

Abelard and Heloise's affair lasted only about 18 months, but it changed their lives. Around 1115, Peter Abelard, already a famous philosopher, set his sights on Heloise, the niece of a local Parisian canon named Fulbert. Before long, she became Abelard's pupil, and then his mistress. When Fulbert found out, he cast out Abelard (who was lodging in Fulbert's house) and, when Heloise became pregnant, forced them to get married. They did so in secret, but Fulbert, still enraged at the loss of his family honor, sent his henchmen to Abelard's house one night, where they castrated him. The brutal act drove Abelard to become a monk and Heloise a nun. Some 12 years after their separation, Abelard wrote the story in a letter to a friend, and somehow Heloise obtained a copy of it. She wrote Abelard, and so began the correspondence that made them famous.

The wherefores of all the goings-on were driven by the politics of the age. Abelard and Heloise's affair took place between the first two crusades, when monasticism was on the rise, and when the reform movement was beginning to take over the monasteries and vilify philosophers. Previously, minor clergy -- including teachers like Abelard attached to a church -- could marry or have concubines; now they were subject to the same laws of chastity as monks. That's why Abelard's relationship with Heloise was a clandestine affair, and why their marriage had to remain secret. But the secrecy of the marriage couldn't restore Fulbert's public honor -- which he had lost when his niece bore a bastard child -- and his rage at Abelard couldn't be assuaged until he took personal vengeance.

Heloise and Abelard were something of a countercultural pair. They named their son Astralabe, after an astronomy instrument -- a bizarre choice in an age when most children were expected to be given Christian names. They had lots of premarital sex, and they wrote about it freely in their early letters. At least once they made love in the refectory of a church. Most dangerously, they applied reason to their lives and their faith, and that made them renegades in the eyes of the ruling reformists.

The basis of Abelard's philosophy, which he taught to Heloise, was that logic had to be applied to religion in order to arrive at the truth. (In fact, he coined the term "theology" -- "God logic.") He believed that one had to be judged by intentions rather than deeds, so knowledge and introspection were everything. It was sinful, in Abelard's view, to recite a prayer that one didn't understand; on the other hand, the Jews that crucified Jesus were sinless, because their intentions were pure. Naturally, such views got him into a lot of trouble. After his castration, Abelard faced two heresy trials, at both of which he was condemned.

Burge deftly analyzes the two trials, which were built on fear and anti-intellectualism similar to what we face today, and casts them as absurdist plays that would be funny if the future of Christian morality had not hung in the balance. In the first, Abelard stood accused of claiming that there was more than one god, because he had written a book that applied logic to the Trinity. His accuser could find nothing in the work that suggested heresy, except for a single sentence that wasn't Abelard's writing but a quote from St. Augustine. Still, Abelard was condemned and ordered to burn his book.

In his second trial, Abelard faced his archenemy, Bernard of Clairvaux, the head of the Cistercians. They were a reformist monastic order that would become the most influential in Christendom, and Bernard was the George W. Bush of their movement. He "was accustomed to having people listen to him and then eventually agree," Burge writes. Bernard was deeply anti-intellectual, casting Abelard as elitist, overeducated and anti-religious. He charged that in Abelard's theology "the faith of simple folk is laughed at, the mysteries of God forced open, the deepest things bandied about in discussion without any reverence." In another letter, Bernard used the logic of preemptive war to persuade the pope to condemn Abelard and his friends: "They have each drawn their bows and filled their quivers with arrows; now they lie in ambush ready to fire at unsuspecting hearts." Bernard would eventually persuade Europe to launch the second crusade -- a military expedition in the Middle East, built on an abstract moral idea, that would result in the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Muslims. Sound familiar?

As Burge writes, the conflict between Abelard and Bernard wasn't one of religious versus secular life, it was "faith with reason versus faith without reason," and faith without reason won in the end. Because Bernard insisted that logic couldn't be applied to religious matters, Abelard was fundamentally unable to argue against him. At the trial itself, Abelard faced a council of bishops who, Burge writes, "were not interested in theology ... They would seize on whatever idea was easiest to grasp." Abelard was condemned, and before he could appeal to the pope, he died.

Burge's fascination with the Middle Ages, according to his biographical blurb, stems from his university study of medieval philosophy, and his enthusiasm pays off in the sections devoted to those ideas. He clearly explains Abelard's theories and his heresy trials and makes us feel the weight and implications of those defeats without moralizing. His writing is best, in fact, when he's connecting Abelard's philosophy to the couple's actions and to the political life around them. When Heloise becomes abbess of the Paraclete -- a monastery that Abelard founded -- Burge portrays the move as not just a practicality but also an event that would make the Paraclete the last feminist holdout against the tide of misogyny threatening women's roles in religious life.

What Burge fails to engage with -- and it is no small failing -- are Heloise's eroticism and, by extension, the sexual life of the couple. For just as Abelard's philosophy dictated their actions, so did Heloise's sexuality fuel the drama that led to Abelard's castration and their later epistolary relationship.

Little is known of Heloise's life, and Burge does his best to spin out her tale from the available scraps of information. Burge admires Heloise -- for her startling frankness about sexual matters and for the exceptional prose that makes her letters powerful and immediate 900 years later. He notes that Heloise never wanted to get married, nor did she want to take the veil after Abelard's castration. She did those things out of submission to her lover, of which she reminds Abelard in her letters. "The name of wife may seem more sacred or more binding," she wrote, "but sweeter for me will always be the word mistress, or, if you will permit me, that of concubine or whore." As for her role as convent abbess, Heloise did not repent of her premarital relationship with Abelard and insisted that she never would.

Burge also discusses Heloise's revolutionary insistence on "the reconciliation of religion and the life of a lover," as well as her seemingly paradoxical ability to exercise free will in the act of submission. But just as he begins to delve into the erotic nature of her relationship with Abelard, he pulls back, and the result is a less-than-full portrait of a sexually complex woman whose ideas were as threatening to the reformist movement as Abelard's were.

Some of Burge's hesitation is understandable; Heloise and Abelard's sex was certainly not mainstream, and reconciling Heloise's submissiveness with her intelligence and her proto-feminism streak is no easy task. In discussing their sex in the church refectory, Burge suggests that Abelard might have forced himself on Heloise against her will, for "she might have had a slightly more developed sense of propriety than he did." But just as likely, such scenarios of domination were part of their erotic play. Abelard mentions twice in the letter to his friend that he used corporal punishment in his lessons with Heloise; Burge doubts that Fulbert would have instructed Abelard to hit his niece, saying that for Abelard "in his mind it was an integral part of the erotic content of the affair." But later Burge points out that Fulbert was prone to rages, so why wouldn't the uncle have allowed Abelard to hit Heloise? And given the dominant/submissive nature of their sex, why wouldn't this have been erotic for Heloise, too? The evidence in Heloise's letters favors a portrait in which submissiveness wasn't just a declaration of love; it was also a turn-on. Look at the orgasmic way she describes taking her vows as a nun, something she never wanted to do:

"I carried out your orders so implicitly that when I was powerless to oppose you in anything, I found strength at your command to destroy myself. I did more -- strange to say -- my love rose to such heights of madness that it robbed itself of what it most desired beyond hope of recovery, when immediately at your bidding I changed my clothing along with my mind, in order to prove you the sole possessor of my body and will alike."

Burge comments that this passage is Heloise at her submissive best, that perhaps she had "that feeling of reckless freedom that comes from the total surrender of the will," but he doesn't take his speculation to the realm of fleshly desire. By shying away from the sexual, he misses some of the best drama in Heloise and Abelard's letter writing. Abelard, after his castration, naturally found himself reevaluating his sense of self, and that self no longer included a place for the erotic. For Heloise, though, the erotic was everything.

Heloise wrote, "Everything we did and also the times and places are stamped on my heart along with your image, so that I live through it all again with you. Even in sleep I know no respite. Sometimes my thoughts are betrayed in a movement of my body, or they break out in an unguarded word." Burge flags this as an exceptional piece of sexual writing, but it's also a calculated attempt by Heloise to induce desire in Abelard, a sort of early phone sex. When Abelard writes back, "I thought that this bitterness of heart at what was so clear an act of divine mercy had long since disappeared," he's not just urging her to accept God's will but also resisting the erotic within himself.

It was Heloise's complex ideas about submissiveness and freedom, about sexuality and religion, that made her famous. What her letters allow us to glimpse is a Christianity that can accommodate eroticism, a faith that doesn't preclude desire. The difference between religious and sexual rapture has always been ambiguous, and more than anyone else of her time, Heloise embodied their fusion. Coupled with Abelard's theories of logic, Heloise's beliefs speak to the constant struggle between the light of reason and the reactionary forces of intolerance. Burge's biography is an excellent study of medieval thought, but it doesn't go quite far enough. By skimming over the erotic, he misses the chance to fully explore what effects this medieval religious conflict had on our ideas of sex and gender. Perhaps his skittishness says more about the time we live in now: one in which sexuality and religion are pitted against each other, in which books that embrace the erotic are often dismissed as little more than pornography. One that, at times, feels positively medieval.

Shares