Once you've seen Steve Ditko's hands, it's hard to forget them. Not the hands of the famously reclusive 77-year-old cartoonist himself -- not many people have seen those. The hands he draws on his characters, though, are unmistakable: expressively gesticulating, fingers pointing in all directions, casting spells or shooting webs or passing judgment. Ditko's never been as well-known as fellow comics pioneers Jack Kirby and Will Eisner. Insisting that his work speaks for itself, he's refused to be photographed or interviewed since the early '60s, and his prickly, loopy individualism has kept fame at bay. But he's the ghost haunting the past 40 years of American comic books.

A cross-section of Ditko's early- to mid-'60s work is reprinted in the new hardcover collection "Steve Ditko: Marvel Visionaries." His artwork is often crude and unpretty on its surface: understated and flat, full of crabbed, ugly characters. It's also impossible to shake. He's a master of composition, body language and storytelling flow, and his best ideas have become part of the visual language of comics. The most famous is the look of Spider-Man, co-created by Ditko with writer Stan Lee in late 1962. Ditko drew the first 38 issues of "The Amazing Spider-Man," the foundation on which every Spider-Man story since then has been built. He also created the famous blue-and-red costume -- a brilliantly weird piece of design, featuring a totally covered-up face imprinted with spider webs, with two enormous white swooshes for eyes.

More importantly, though, Ditko devised the visual tone of Spider-Man comics: imperfect bodies perpetually moving through real space. Nobody ever looks especially healthy in his "Amazing Spider-Man." Peter Parker, in or out of his costume, is a scrawny kid with insectoid body language (the specific poses Ditko drew him in were imitated successfully in both of the recent "Spider-Man" movies); Dr. Octopus is a sweaty creep with a terrible bowl haircut. Mary Jane Watson's model-perfect face famously didn't appear on-panel until Ditko had left the series and John Romita replaced him. When there's sexual tension in Ditko's "Spider-Man," there always seems to be something repressed and curdled about it. (He shared a studio for years with bondage/fetish artist Eric Stanton and has claimed they didn't collaborate, but Blake Bell, who's writing a book about Ditko, has a Web site on which he points out some work credited to Stanton that's clearly Ditko's -- look at those hands.)

More importantly, though, Ditko devised the visual tone of Spider-Man comics: imperfect bodies perpetually moving through real space. Nobody ever looks especially healthy in his "Amazing Spider-Man." Peter Parker, in or out of his costume, is a scrawny kid with insectoid body language (the specific poses Ditko drew him in were imitated successfully in both of the recent "Spider-Man" movies); Dr. Octopus is a sweaty creep with a terrible bowl haircut. Mary Jane Watson's model-perfect face famously didn't appear on-panel until Ditko had left the series and John Romita replaced him. When there's sexual tension in Ditko's "Spider-Man," there always seems to be something repressed and curdled about it. (He shared a studio for years with bondage/fetish artist Eric Stanton and has claimed they didn't collaborate, but Blake Bell, who's writing a book about Ditko, has a Web site on which he points out some work credited to Stanton that's clearly Ditko's -- look at those hands.)

The setting for Ditko's "Spider-Man" is a hyper-real New York City, nothing but skyscrapers and water towers and docks. And its characters are always seen in choreographed motion: diving into upside-down springs, leaping, ducking, moving around each other. Every panel is a pregnant moment; you can sense the arc of each character's movement from one image to the next. Stan Lee's dialogue and captions are sometimes charmingly corny, sometimes just glib and annoying, but you don't need them anyway: You can tell exactly what's happening without reading a word. (Spider-Man's mask eliminates his facial expressions, so Ditko makes him communicate everything with his body.)

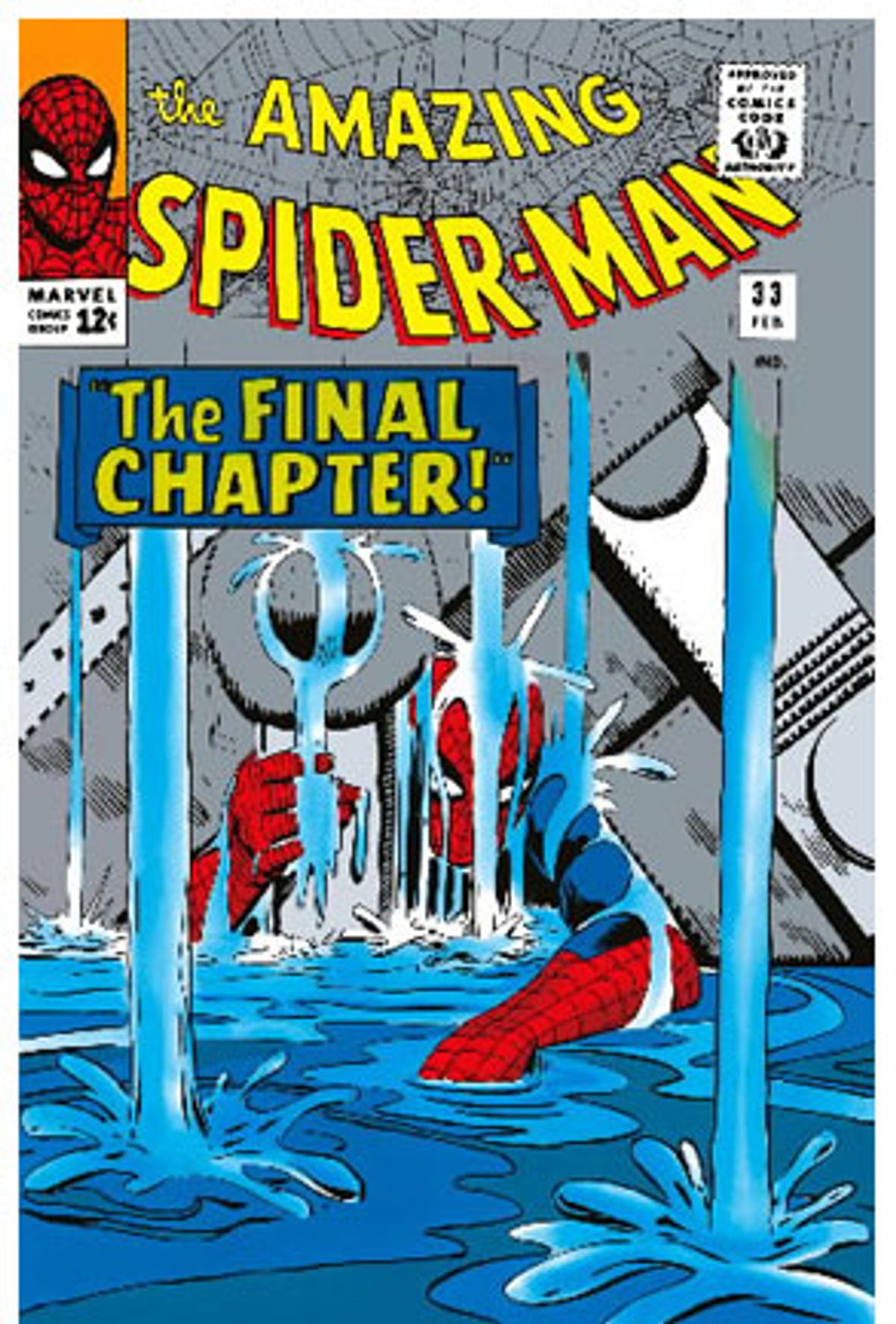

"Steve Ditko: Marvel Visionaries" inevitably includes "The Amazing Spider-Man" Nos. 31 to 33, from 1965 and 1966, by which point Ditko was plotting the series entirely by himself. The pages of No. 33 in which Spider-Man lifts and crawls out from under an enormous piece of machinery in a flooding room are the comics' equivalent of the Odessa Steps sequence from Sergei Eisenstein's "Battleship Potemkin" -- a scene so formally masterful that every subsequent cartoonist has internalized it, even those whose work has nothing to do with superhero stuff. ("Love and Rockets'" Jaime Hernandez includes a wickedly funny little homage to it in his graphic novel "Locas.")

At the same time, Ditko was developing a very different visual style for his other major collaboration with Lee, the "Dr. Strange" stories about a "master of the mystic arts" that originally appeared in "Strange Tales." (Five of them are reprinted in "Marvel Visionaries.") "Spider-Man's" characters struggled against the laws of physics in a stylized representation of the real world; "Dr. Strange's" characters were freed from those laws and that world altogether, floating freely in other-dimensional space filled with curving, squiggling design elements. There are almost no right angles in Ditko's "Dr. Strange" stories other than panel borders. Over and over, though, there are images of weirdly shaped portals through which even weirder planes of existence can be seen, and the implication is that the rectangles on the printed page act as the same sort of portal for the reader.

Dr. Strange supposedly lives in New York City, too, but virtually all we see of it is his Greenwich Village townhouse, as curvy and un-New York-like as one of Rudolf Steiner's Goetheanum buildings. Every few panels there's a new psychedelic explosion; Strange's nemesis is Dormammu, a "dweller in the realm of darkness," whose head is an indistinct, striated red shape with holes where its eyes and mouth should be, surrounded by billowing yellow flames. If "Spider-Man" was, at its core, a vehicle for exploring the relationship between power and personal responsibility, "Dr. Strange" was, whether or not Ditko and Lee acknowledged it, a vehicle for talking about drug culture.

Dr. Strange supposedly lives in New York City, too, but virtually all we see of it is his Greenwich Village townhouse, as curvy and un-New York-like as one of Rudolf Steiner's Goetheanum buildings. Every few panels there's a new psychedelic explosion; Strange's nemesis is Dormammu, a "dweller in the realm of darkness," whose head is an indistinct, striated red shape with holes where its eyes and mouth should be, surrounded by billowing yellow flames. If "Spider-Man" was, at its core, a vehicle for exploring the relationship between power and personal responsibility, "Dr. Strange" was, whether or not Ditko and Lee acknowledged it, a vehicle for talking about drug culture.

Sixties hipsters thought that Ditko's urban realism and trippy visions meant that he was one of them. They couldn't have been much more wrong. Around the time that Ditko fell out with Marvel Comics in 1966, he became fascinated with Ayn Rand and objectivism, and his work started to take on a severe and increasingly strident right-wing tone. He spent a few years working for the small company Charlton Comics, where his most significant creation was the Question: a hero in a suit, hat and tie, with no face -- just a blank pink blot -- and a ruthless contempt for moral relativism. At a subsequent stint with DC Comics, he created the Hawk and the Dove (a pair of superhero brothers, whose personalities were exactly what you'd guess) and the Creeper (a yellow-skinned, green-haired, red-maned, screeching maniac).

And then, by the end of the '60s, Ditko retreated into the world of the small press -- fanzines and self-published comics -- where he could write and draw whatever he pleased. Comics like "Mr. A" and "Avenging World" became his venue to rant semi-intelligibly about objectivism, how there's no middle ground or gray area in morality, and so on. He spent most of the next 30 years creating Rand-inspired comics that are beautifully designed and composed but almost unreadable; they're explicitly didactic, but so heavy-handed that it's impossible to imagine them swaying anyone's opinions. (Ditko continued to draw hundreds of pages a year through the '90s but hasn't published any new work since 2000.)

After 1970, he occasionally returned to mainstream comics, but his only major new creation was a bizarre and short-lived mid-'70s series, "Shade the Changing Man." (It was ahead of its time; revived in 1990 by writer Peter Milligan without Ditko, it ran for six years.) "Marvel Visionaries" leaps from 1966 to two stories originally published in 1980, one from 1988, and one from 1992, in which Ditko's phoning it in, barely bothering with even basic anatomy and perspective.

By then, though, Ditko's fingerprints were all over the comics world. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' landmark "Watchmen" is, in some sense, one long tribute to Ditko, from its nine-panel grid to the character of Rorschach, whose appearance and inflexible morality are directly inspired by the Question and Mr. A. Before Todd McFarlane created his hugely popular horror comic "Spawn," he made his name with work on "Spider-Man" that was a slicked-up variation on Ditko's style. Peter Bagge ("Hate") wrote and drew a Ditko parody a few years ago, "The Megalomaniacal Spider-Man," in which Peter Parker becomes obsessed with objectivism. And near the end of Neil Gaiman and Andy Kubert's recent graphic novel "1602," there's a scene in which we briefly see another dimension -- an image that's directly lifted from (and credited to) a 40-year-old Ditko "Dr. Strange" story, since there's no way anyone else could have captured that otherworldliness better.

Most of what's in Ditko's "Marvel Visionaries" volume are stories that have been reprinted to death already, fine as some of them are. But it also includes some remarkable, long-unseen material: 10 short horror, suspense and science fiction stories he collaborated on with Lee for anthology comics like "Tales to Astonish" and "Amazing Adult Fantasy" between 1961 and 1963. Lee knew how to spur Ditko to do his best work, and these corny twist-ending tales are drawn with the single-minded force of nightmares.  The artwork is largely close-up shots of distressed characters, with little or no background, which makes the world they inhabit seem as suffocatingly tiny as the scope of the stories themselves. "Help!" opens with an image of a man clasping his ears as he's surrounded by seven screaming disembodied mouths; "Those Who Change" begins with a gigantic close-up of a huge-eyed reptile's head beginning to emerge from prehistoric ooze. The blunt alienation of these early pieces is still shocking now, and the way Ditko draws the characters' hands alone tells the stories almost as much as Lee's words.

The artwork is largely close-up shots of distressed characters, with little or no background, which makes the world they inhabit seem as suffocatingly tiny as the scope of the stories themselves. "Help!" opens with an image of a man clasping his ears as he's surrounded by seven screaming disembodied mouths; "Those Who Change" begins with a gigantic close-up of a huge-eyed reptile's head beginning to emerge from prehistoric ooze. The blunt alienation of these early pieces is still shocking now, and the way Ditko draws the characters' hands alone tells the stories almost as much as Lee's words.

Douglas Wolk's writing on comics and graphic novels will appear the first Friday of each month in Salon Books.

Shares