In the old days, when it was time to get married, your dad would just go over to the next village with a nice-looking cow and a string of puka beads and parade them in front of the family of a nice boy. If the settlement was acceptable to them, you'd become a blushing bride -- no muss, no fuss. You might not like your husband -- you might be lucky if you could even stand the sight of his face -- but at the very least, you knew where you stood. You'd entered a contract. You'd have the babies, cook the food and keep the home nice, and in return, with luck, you'd be well taken care of and possibly not even get beaten. The world fell into place accordingly.

But somewhere along the way, feelings entered the picture. And feelings, as Laura Kipnis will tell you in "Against Love: A Polemic" always muck things up. Because of feelings, people are drawn into those cozily familiar formations known as couples. But also because of feelings -- and because, as Kipnis reminds us, Freud noted that there's a very thin line between disgust and desire -- even the loveliest comforts of coupledom can become stifling, leading first to bad stuff (restlessness, vague feelings of wanting something more) and then, possibly, to really bad stuff: In the worst-case scenarios, formerly contented domestic partners become sex-mad Hester Prynnes, scarlet-lettering all over the place. If they're lucky, they can clean it all up after the fact with a little self-knowledge via marital counseling (all the better, in some cases, to start the cycle all over again); if they're unlucky, they end up in divorce court.

Welcome to the miserable world of modern marriage.

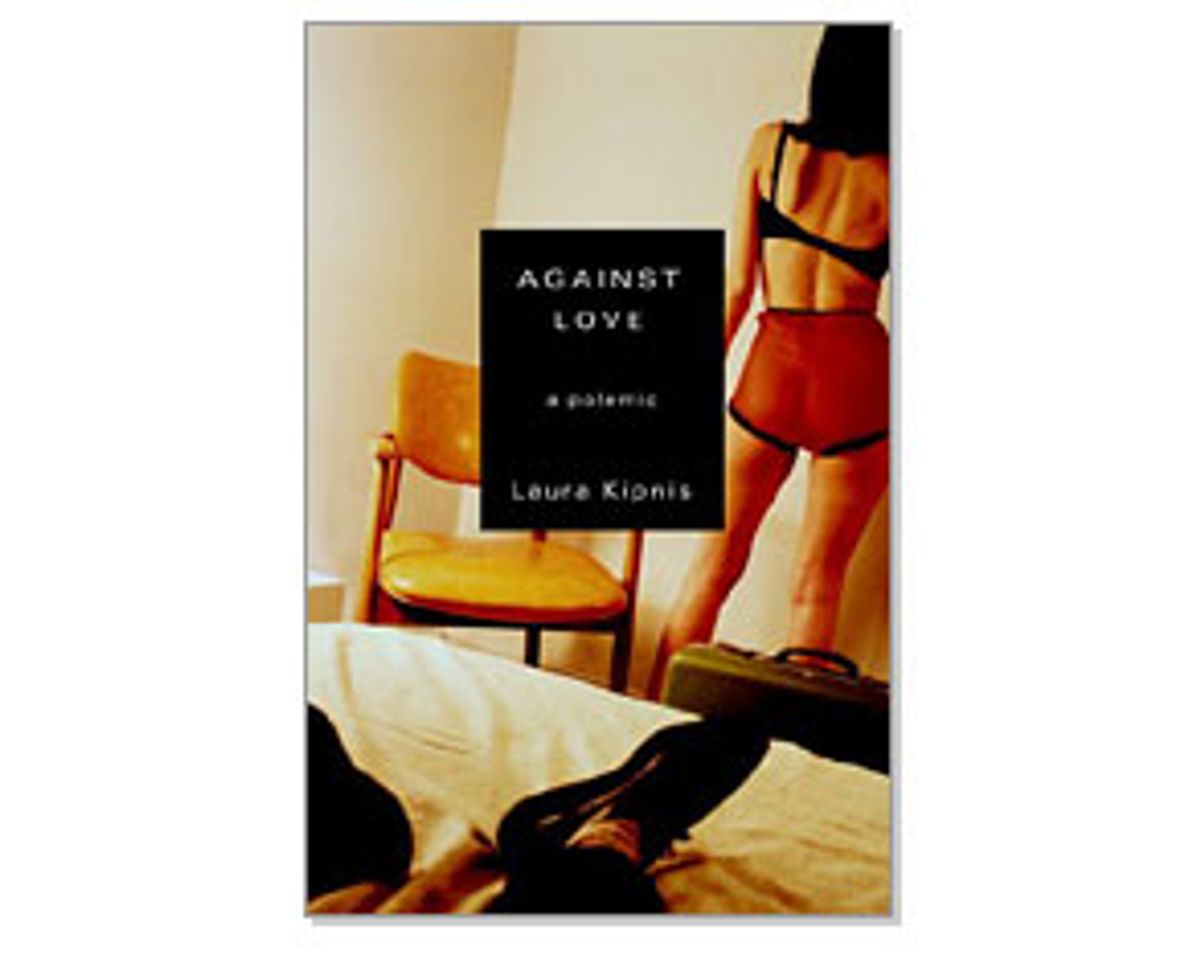

So why is Kipnis' book, which addresses this mess in unsparing detail, such a delight -- in the broadest sense of the word, that is? Reading "Against Love," I felt invigorated half the time and plunged into the deepest, most morose pit of self-pitying despair the rest of it -- in other words, I felt as if I were in love. That seems to have been Kipnis' aim. Her book isn't called a polemic for nothing, which means, as she explains in the introduction, it's designed to turn us upside-down: "Polemics exist to poke holes in cultural pieties and turn received wisdom on its head, even about sacrosanct subjects like love. A polemic is designed to be the prose equivalent of a small explosive device placed under your E-Z-Boy lounger. It won't injure you (well, not severely); it's just supposed to shake things up and rattle a few convictions."

Let's forget that Kipnis even needs to explain what a polemic is. My guess is that she wanted to stem the tide of letters from serious-minded cuddlebugs everywhere, taking pen to paper to assert angrily, "We happen to like being married!" And also to counteract the measured dullness of certain types of book reviewers who feel it's their civic duty to point out all the positive aspects of marriage that Kipnis has failed to deal with -- probably because she's smart enough to know that they're boring as hell to read about.

Instead, Kipnis goes right for the juice: The break for some kind of freedom, that desperate dash for relief from the erotic drudgery of married life -- adultery. "Against Love" could be considered a "defense" of adultery, but it's more accurate to call it an examination of the effects, both positive and negative, that fooling around can have on the fabric of our society. Because as incendiary as the title of Kipnis' book is -- and she hints broadly that it's a title with more than one meaning -- Kipnis doesn't seem to be particularly against love at all. What she's really against are our collective grand expectations of what it means to be part of a couple, expectations that don't take into account the fact that we're all human beings and thus liable to change, in highly unpredictable ways, at any moment. Our idea of marriage doesn't allow for fluidity and openness, and that may not be completely our fault. Because, in Kipnis' view, there are strong societal forces at work that depend on our swallowing, hook, line and sinker, the notion of marriage as a romantic institution. (By "marriage," Kipnis means any long-term romantic partnership, gay, lesbian or straight.) Submerged in the marital jelly of docility and numbness, we're much more productive and easier to manage. We work hard all the livelong day, and then come home, where we work hard at being married, because we all know that "Marriage is hard work." And then, before we know it, all our hard work has killed our libidos, leaving them limp and lifeless and hanging like damp, dejected rags on the clothesline of life.

Cheering, isn't it? And yet there's something bracing about the way Kipnis states the obvious without feeling the need to temper her "cons" with any of those pesky "pros." Who ever comes out and says this stuff? Because face it: Most of us who have spent any length of time in a good relationship (even one that's eventually gone bad) already know what the benefits are. What's harder is admitting that there are elements of long-term partnership that just plain suck. It's not such a stretch to believe that society at large as well as our government have a vested interest in keeping us anesthetized (but always working hard!) in the marital cocoon.

In one of her first audacious acts, Kipnis applies Marxist theory to the marriage contract. "Marx's question remains our own to this day: just how long should we have to work before we get to quit and goof around, and still get a living wage?" If marriage is just another kind of work, where does pleasure come in? Kipnis asks. But then, pleasure and leisure time are dangerous. "'Free time and you free people,' as the old labor slogan used to go," Kipnis writes. "Of course, free people might pose social dangers. Who knows what mischief they'd get up? What other demands would come next?"

Then Kipnis limns a nightmare version of married life that, you have to admit, isn't exactly wrong. This chapter is called "Domestic Gulags," and I highly recommend that you read it late at night (when the potential for self-doubt and self-loathing runs merrily high in most of us), nestled right up against your peacefully snoring, and possibly cheating, partner. If you happen to have a set of headphones and a loop tape of Vincent Price's maniacal house-of-horror laughter, you might want to set that going as well. Kipnis devotes a full eight pages to a wild and witty list of all the things you can't do when you're part of a couple, beginning with "You can't leave the house without saying where you're going" and ending with "You can't return the rent-a-car without throwing out the garbage because the mate thinks it looks bad, even if you insist that cleaning the car is rolled into the rates." (Somewhere in there you'll find "You can't wear mismatched clothes, even in the interest of being perversely defiant" and the ever-popular "You can't use the 'wrong tone of voice,' and you can't deny the wrong-tone-of-voice accusation when it's made.")

In the Kipnis marriage universe, coupled partners learn to tolerate each other, but barely. They're people with mutual needs that have to be met, but to meet them, you usually have to guess what they are first, unless, of course, they're enumerated for you regularly in a shrill lecture. And forget the fact that sexual desire in human beings is disorderly and unpredictable: We're expected to pick a partner and stick with him or her forever, claiming that we have achieved "mature love" when the sex becomes boring or nonexistent.

The point is that marriage, which ostensibly jerks us into a lockstep of manageability that should ideally last a lifetime, serves society more than it serves the human spirit. And that's where the idea of adultery as civil disobedience comes in. Kipnis isn't interested in feelings here: What she really cares about are social patterns. (More than once she sends out a message to the aggrieved partners of cheating spouses everywhere -- a shout-out along the lines of Bill Clinton's "I feel your pain.") And adultery, for all its bad juju, does have its good points.

For one thing, it completely confounds your sense of time, and, as Kipnis wisely observes, "Time organizes us as selves, from the inside out ... Even small protests against time-management are worth some attention, because screw around with time and, in fact, you're adulterating the very glue of orderly social existence."

Adultery is a form of risk-taking, a renegade act, a reaffirmation that, OK, we may be married, but we're not dead. We're humans with "messy subjectivities." Adultery is a kind of performance art (Kipnis refers to it, more than once, as "acting out") in which "conventions are defied; chance elements introduced; new viewpoints engineered."

All of this would lead you to believe that Kipnis is rather fond of adulterers as a lot, and that's probably true in theory, at least. But if you think she's rough on the poor, ordinary well-meaning Joes who are just trying to slog through their marriages by bringing home the occasional éclair for a neglected spouse (and the power of an occasional éclair should never be underestimated), just see what she has to say about the ones who stray. These are the people who succumb to the charms of a third party and who explain their behavior with phrases like "Something just happened to me!" and "I feel so alive!"

Kipnis acknowledges that love affairs can feel completely transforming; with this new third party, you can surrender to long-buried feelings; ordinary conversations glisten and gleam. "But what really keeps you glued to the phone till all hours of the night -- conversations sparkling with soulfulness and depth you hadn't known you possessed, exchanging those searching whispered intimacies -- is a very different new love-object: yourself. The new beloved mirrors this fascinating new self back to you, and admit it, you're madly in love with both of them."

Ouch. But then, if you're going to be hit with the truth, why not get it right between the eyes? If you read between the lines -- and what else are lines for? -- Kipnis isn't really pro-adultery any more than she's actually against love. (This is a polemic, remember?) But when she expands her argument, arguing that the hallowed halls of our government have much to lose if people either don't marry or don't stay married, she really gets cooking. Kipnis enumerates, with unrepressed glee, most of the politicians in recent history who have espoused family values only to be embarrassed by a naked mistress or two in their own closets. She's reasonably sympathetic to Bill and Hillary Clinton on the subject of their highly public marital woes. But she also has a long and sharp memory, and she reminds us that Hillary, while stumping for her New York Senate seat, once asserted that our leaders should "start talking about the importance of marriage."

And, she reminds us, Bill Clinton, with Hillary's support, signed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which she calls "a custom-built stockade fence to protect matrimony against infiltration by nefarious homosexual elements and safeguard the more panicky states from having to recognize another state's gay marriages, should any state actually grant the privilege, which none had." (She also devotes a few pages to the notion that as messed-up an institution as marriage is, the fact that gay men and lesbians want in only proves how ingrained it is in us that marriage is both necessary and good.)

Kipnis has the knives sharpened and ready for anyone who believes that solid, wholesome marriages, in which all problems or even potential problems are swept under the rug by both partners, are somehow good "for the sake of the children." Kipnis cites how little we spend on education as a nation, and she also notes that one in five American kids live in poverty. "Sentimentality about children's welfare comes and goes, apparently: highest when there's the chance to moralize about adult behavior, lowest when it comes to resource allocation."

It is, after all, healthy-looking marriages, if not actual healthy ones, that keep our nation going. Which is why, among politicians and regular citizens alike, deceit is sometimes necessary (if unfortunate, considering how devastating it can be to the parties involved) in keeping up that shiny-coat, wet-nose marital appearance. "Let's recall that the marriage vow isn't only to a spouse, it's to the institution and to every strained metaphor that it sustains, and to every other relationship and household and ego defense sustained by it in turn. Clearly if there were a Starr Report on every American marriage, the institution would instantly crumble, never to recover. And what, then, of the republic? Citizens obviously have a duty to lie about their sex lives, as Clinton himself knew -- and tried valiantly to do."

Lying, cheating, getting away with all kinds of shenanigans short of murder (and sometimes even that): Is this what marriage means today? Kipnis has some problems with the idea of marriage, that's for sure. But her book doesn't offer any viable solutions: In other words, she throws the bomb and then she runs. Fast.

But you can't fault her for that, any more than you can fault most of us for either becoming part of a couple or, at one time or another, yearning to become part of one. When pressed for an alternative to love, Kipnis, like the rest of us, doesn't have an answer.

But she sure does have a sense of humor. As intellectual tracts go, "Against Love" is hugely entertaining. I can't remember the last time a Marxist-leaning academic made laugh out loud, so heartily and so often. I have not been able to decide whether "Against Love" is scary-funny or funny-scary, so I'll leave it suspended somewhere nebulously between the two.

If you're not currently coupled and don't ever want to be, run, don't walk, to the bookstore and buy "Against Love." If, on the other hand, you've already consigned yourself to what generally passes for marital bliss, "Against Love" at least offers the comfort of knowing you're not alone. Yes, you married a monster from outer space, but relax, it's OK. We're all in this universe together.

Shares