Last July, Chief Justice John Roberts -- one of four votes on the "conservative" wing of our closely divided Supreme Court -- was rushed to the hospital following a seizure. At a human level, the news was gripping: a young man, the father of small children, forcefully reminded of his mortality.

But Roberts' private trauma has much wider implications for the country, which we can only dimly foresee. A uniquely powerful, uniquely American institution made up of unelected lawyers, the Supreme Court is dependent on the unpredictable fortunes of the nine ordinary mortals who make it up.

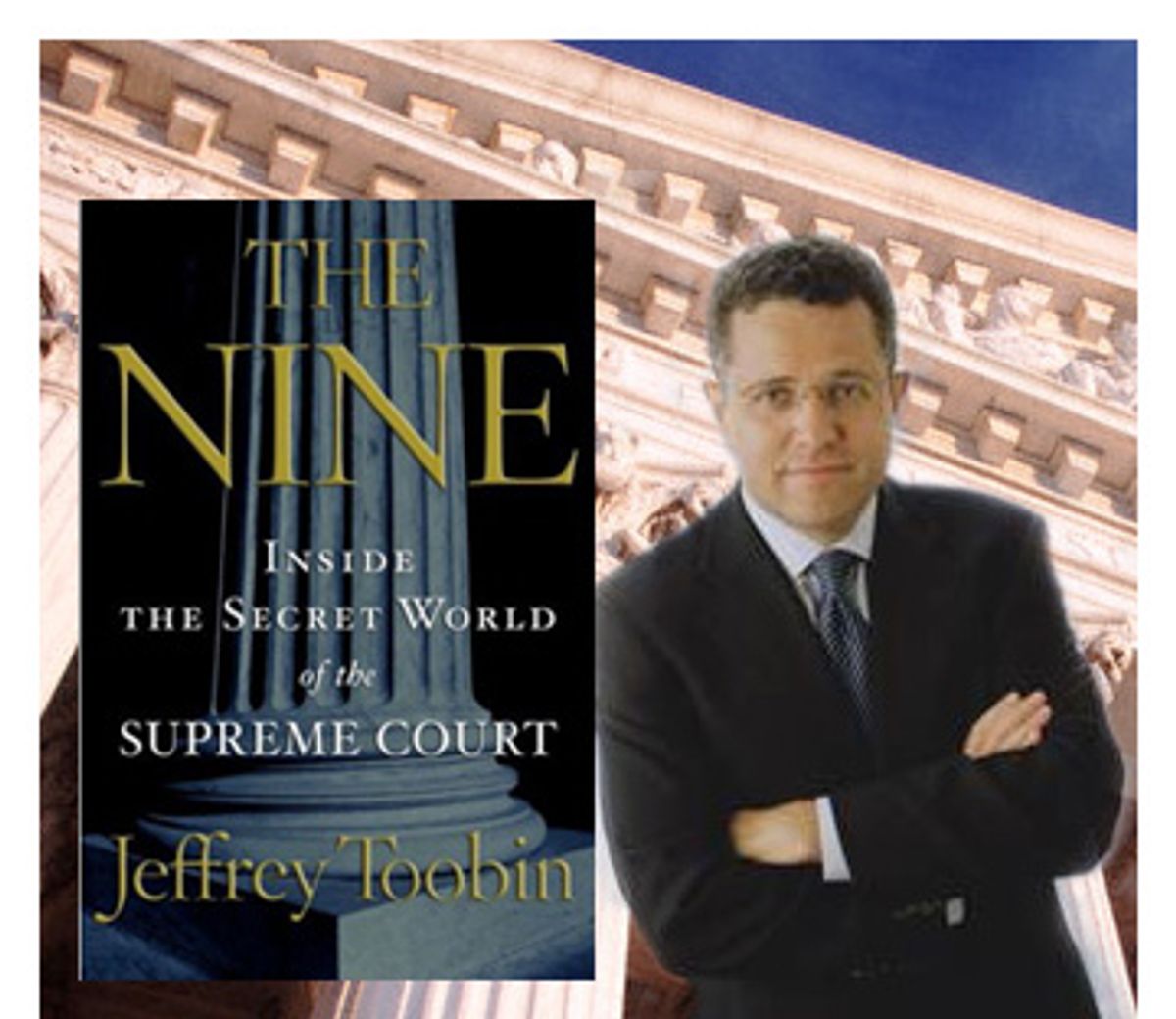

"The Nine," the latest book from the indefatigable New Yorker legal correspondent Jeffrey Toobin, provides fascinating glimpses into the humanity of these mortals. But in the end, Toobin falls prey to the temptation to reduce them to "conservative" or "liberal" votes. That temptation is widespread in media coverage of the court, and often obscures the real process of change that takes place inside its closed chambers.

Sheltered by life tenure, and surrounded by deference and flattery, the justices live in an airless bubble even harder to penetrate than the one surrounding stubborn presidents. Events outside can seem distorted or far away; developments inside -- many invisible to the larger public -- can take on outsize importance. Each justice influences the others in ways that are hard even for those involved to understand. One may be alienated by his nominal allies; another may find himself unexpectedly beguiled by the "enemy." Justices sometimes migrate permanently (Harry Blackmun was a rock-ribbed conservative when named to the court) or move back and forth depending on events inside and outside the court (as Justice Anthony Kennedy sometimes seemed to do on the Rehnquist Court between his appointment in 1987 and the chief justice's death in 2005). The result is an institution that has often defied the predictions of seasoned analysts and observers. Present appearances to the contrary, it may do so again.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

A generation ago, the financial writer Burton Malkiel suggested that the motions of the stock market, though in broad outline reflective of economic trends, were random and unpredictable from day to day. A similar case, it seems to me, can be made for the Supreme Court. Courts move in broad directions as a result of the political leanings of new justices; but in individual cases they can be quirky and unpredictable.

Being one of the nine is different from being an advocate on the outside, or even from being one of the nearly 180 appellate judges on the federal courts. A justice's vote can shift history, and that responsibility can change the way he or she looks at issues. "When you put on the black robe, the experience is sobering," Justice Lewis F. Powell once said. "It makes you more thoughtful." The justices, in fact, may sometimes take their own importance a bit too seriously. Toobin quotes the more histrionic Justice Kennedy, moments before going into court to announce a key ruling, as saying to a reporter, "Sometimes you don't know if you're Caesar about to cross the Rubicon or Captain Queeg cutting your own tow line."

Kennedy occupies the swing-vote position on this court that Powell occupied during the '70s and '80s. Summarizing the 2006-07 term, Toobin writes, "No justice in history had had a term like his; in the twenty-four cases decided by votes of five-to-four, Kennedy was in the majority in every single one." The justice in the center can have an outsize influence -- and not just when the votes are counted. Other justices know they must win the swing vote, and they often tailor their constitutional arguments in an attempt to read his or her mind. But of course the reverse is also true -- the justice who seeks the center will very often find him- or herself moving right or left according to the pull of the opposing wings.

The story of the court's swing votes -- from Powell in the '80s to Sandra Day O'Connor until her retirement in 2005 to Kennedy today -- maps a fairly steady pilgrimage to the right. But that pilgrimage has included detours that defied nose-counting projections. The Rehnquist Court refused to overturn Roe v. Wade or Miranda v. Arizona, pulled away from rigid limits on federal power, and even reaffirmed a limited role for racial preferences in higher education -- all disappointments to the conservative presidents who nominated six of the current nine. It also extended the right of privacy to cover the choice of consenting adults to have sex -- gay or straight -- in their own homes.

To Toobin, these detours, not the overall conservative trend, truly define the meaning of the Rehnquist Court. After Bush v. Gore, he argues, the court set off "in its most liberal direction in years." But he warns that those days are over. The appointments of Roberts and Samuel Alito, he says, mark the ascendancy of the "movement conservatives," prepared to use their power of judicial review to block political initiatives to protect civil rights, free speech and the environment. Long frustrated by the unpredictability of Republican appointees like O'Connor and David Souter, Toobin says, the members of the legal hard right "are very close to total control."

"The Nine" generates its story arc by overemphasizing the liberal detour after 2000 to set up a coming violent swing to the right. It covers much of the same ground as "Supreme Conflict" by ABC News correspondent Jan Crawford Greenberg. Greenberg got deeper inside the court's bubble, with background interviews with nine justices and extensive on-the-record comment from Justice O'Connor. Toobin is a tireless reporter, but his beat at the New Yorker is much wider than the Supreme Court, and he is at his best covering volatile stories like the O.J. Simpson case or the Florida recount. He has a less sure feel than Greenberg for the constitutional issues that dominate the Supreme Court's agenda.

Within these limits, though, "The Nine" is entertaining and illuminating. Toobin draws a vivid and irreverent picture of the justices; it's best summarized in his estimation of seven justices' performance in Bush v. Gore. In his account, Chief Justice Rehnquist is slapdash and result-oriented; O'Connor, image-conscious; Kennedy, bloviated and incoherent; Antonin Scalia a self-righteous bully; Clarence Thomas, withdrawn and rigid. The two Clinton appointees, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, are portrayed as timid and flabby. Only Justice John Paul Stevens emerges as an admirable jurist, though any personal picture of Stevens is largely absent from "The Nine." By contrast, Toobin draws a moving portrait of David Souter, whose faith in moderate-conservative judging was nearly shattered by the haste and fatuousness of the court's interference in the election. "There were times when David Souter thought of Bush v. Gore and wept," he writes.

His portrait of swing-vote Kennedy is particularly merciless. "More than any of the other justices, Kennedy loved drama and what he called 'the poetry of the law.' Kennedy's vanity was generally harmless, almost charming -- sort of like the carpet in his office." But Toobin suggests that it was Kennedy's grandiosity and love of excitement that drove the court's disastrous involvement in Bush v. Gore, a decision in which, he notes, the court disgraced itself by the "inept and unsavory manner that the justices exercised their power."

Some readers may question whether these portraits do full justice to their subjects. Greenberg's book draws a more subtle portrait of the complex interaction among the justices. Toobin writes that Clarence Thomas has been "ideologically isolated, strategically marginal, and, in oral argument, embarrassingly silent." Greenburg shows that Thomas in fact has influenced his conservative colleagues, and suggests that it is Scalia who tends to march in step with Thomas rather than vice-versa, as many commentators suggest.

As for Rehnquist, the latter years of his court seem to me more suggestive of the random day-to-day fluctuations Burton Malkiel saw in the stock market than of any kind of concerted lurch to the left. To support his liberal-detour thesis, Toobin de-emphasizes or blurs the real hard-right aspects of that court's jurisprudence. Of the court's federalism and civil-rights cases, he writes, "the Court limited Congress's right to pass laws that gave citizens the opportunity to sue state officials; similarly, they interpreted federal statutes so that they did not give citizens the right to sue states. These were important, but hardly revolutionary, limitations on federal power, with little practical impact on the lives of most people." And he states offhandedly that the Rehnquist years saw "real, but also modest, movement to the right on church-state issues."

In fact, the civil-rights cutbacks are of great practical importance. Congress has repeatedly passed civil rights statutes to protect racial minorities, women and the disabled; time and time again, the right wing of the Rehnquist Court threw the supposed beneficiaries out of court. In church-state relations, the court was not modest, but revolutionary: it has now cleared the way for direct payments of tax funds to religious institutions. (Read properly, the Roberts Court's decision last June closing the courthouse doors to most future challenges under the Establishment Clause is just an extension of that revolution.) In this analysis, milestones like Lawrence v. Texas, striking down laws against gay sex, are outliers on a curve that bends to the right side of the graph.

Toobin's idea of the Rehnquist Court as a moderate court that sometimes reached liberal results reflects lack of a larger context. In fact, there hasn't been a real judicial liberal among the nine since Justice Blackmun retired in 1994. Even Bill Clinton's two appointees, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, are at best cautious moderates who often fold their cards under pressure from their brethren.

The so-called liberal wing of the court -- John Paul Stevens, David Souter, Ginsburg and Breyer -- is actually made up of old-style judicial conservatives. They respect precedent and view the court's role as modestly building on and explaining the work it has done before. Not a one of them shows any enthusiasm for interpreting the Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment in radical new ways, as former justices like William Brennan and William O. Douglas did brilliantly.

The real energy in the current court resides in the conservative wing -- Roberts, Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. To them, precedent means little or nothing if it does not fit with conservative ideology, and the court's job is to drive the law -- and the nation -- far to the right.

The Roberts Court will continue its move to the right. Its most important recent decisions give a hint of the route the court is mostly likely to follow. In cases involving "partial-birth" abortion, church-state relations, school integration and free speech in public schools, the new majority proclaims its fidelity to uncongenial precedent -- and then reinterprets the previous cases until literally nothing is left of them.

If the current trend continues, this court could be the radical anchor conservatives have dreamed of, taking on the role of guarding (as did the now-discredited conservative court of the early New Deal era) against social and political change favored by political majorities.

But will it continue? This brings us back to John Roberts' moment of vulnerability. Toobin correctly notes that the true nature of the Roberts Court will depend powerfully on the outcome of the presidential election next year. Justice Stevens is 87, though hale; Justice Kennedy is 71; Justice Ginsburg is 74 and has suffered from colon cancer; Justice Scalia is 70 and, it must be said, acting very strangely. Each new nominee will not just affect the vote total, but the thinking of their fellow residents of the bubble.

The unpredictable dynamics among the nine -- and the personalities of those named to join them -- may matter, in the long run, more than any agenda they brought with them from outside. Bill Clinton persistently wooed Mario Cuomo for the seat that eventually went to Ruth Ginsburg; one can only imagine how Cuomo's force of personality and charm might have changed the mix in the last decade. A Democratic president who could put even one bold, persuasive liberal on the court might see more change than raw nose-counting would suggest.

Progressives have despaired of the court over and over since Richard Nixon was elected in 1968. And yet the court has surprised us repeatedly before. Toobin suggests that the surprises are over; but despair is not the true lesson of "The Nine." Sober realism is, to be sure -- but hope as well.

Shares