Recently, a critic in the Guardian lamented the lack of serious fiction concerned with modern warfare. Where, he wondered, was the great modern war novel?

He was wrong. There are tons of books dealing with the "war on terror," 9/11, and the new American engagement with the world. I edited two anthologies of fiction dealing with those very issues.

Or maybe he wasn't wrong. Maybe we just haven't seen the right book. As Norman Mailer wrote in "Advertisements for Myself," "Major war novels are not difficult to write -- it is just difficult to find writers of sizable talent who come close to war."

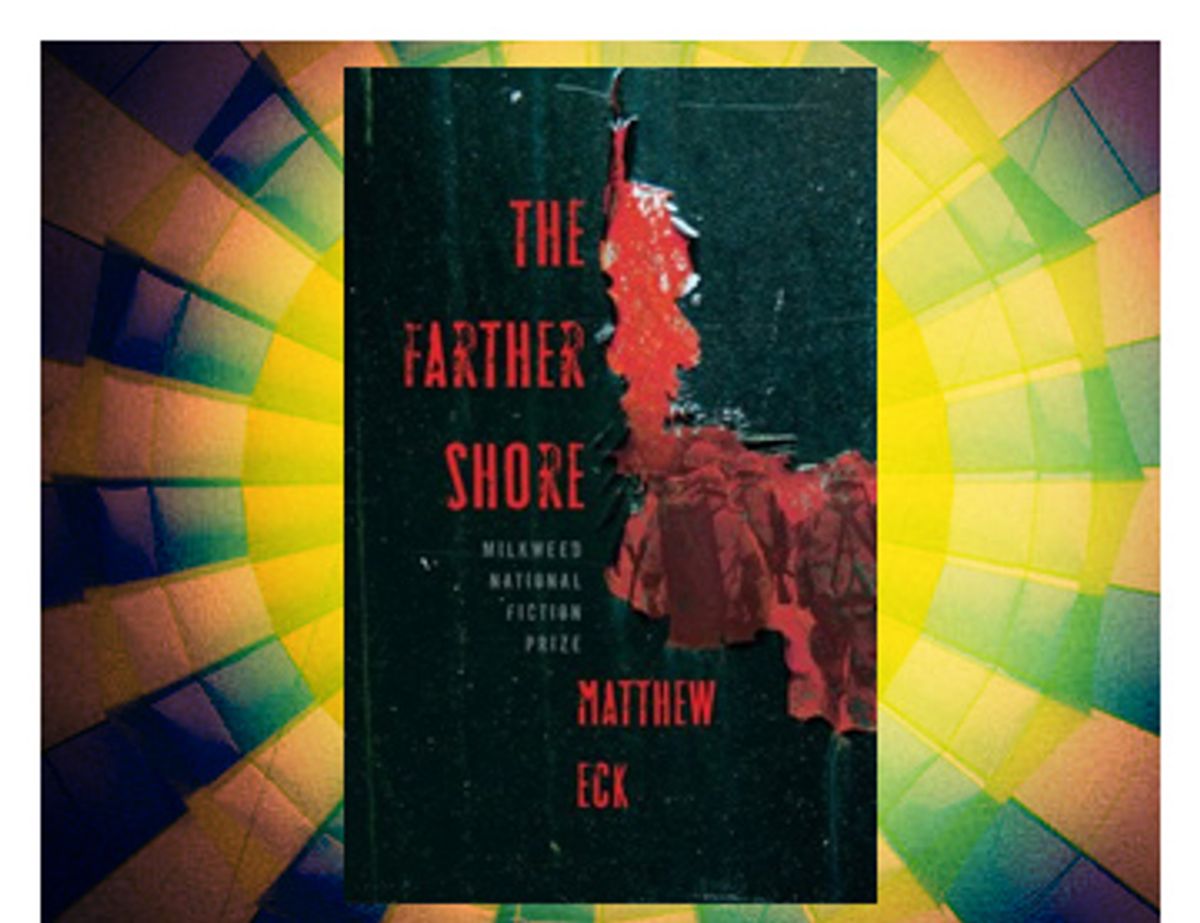

I just finished reading a truly great war novel by a writer of sizable talent who has come close to war. The writer is Matthew Eck, a soldier who served in Haiti and Somalia. His novel, "The Farther Shore," is a haunting portrait of modern warfare set in an African city governed by warlords robbing the population of international aid. The war Eck writes about is conducted in covert missions -- small groups of soldiers guiding bombs from a hidden rooftop -- rather than full-scale engagements between uniformed forces.

The old war novels concerned soldiers surrounded by hundreds, thousands, of other soldiers who represented nations fully aware of the engagements and the sacrifices required. Those books were often set in occupied countries, or they climaxed when one large group of men outmaneuvered another large group of men. But war no longer follows those rules. There is no draft. In response to the attacks of 9/11, our president urged the population to keep shopping. Meanwhile, the battlefield has shifted. It has become increasingly difficult to separate friend from enemy. The target is often a sect, a small group within a much larger population. Some of these conflicts are so small they hardly make the news, and we remain blissfully unaware of the men and women that taste blood and fight battles in our name.

Narrated by Joshua Stantz (an average boy becoming a man who was simply looking for college money when he enlisted), "The Farther Shore" opens on a rooftop in a strange city seemingly modeled on Mogadishu in the 1990s. Six soldiers guide bombs down on the city, the plan being to awe the population into surrender, or something like that. The soldiers don't seem sure. They're just doing their job.

Josh didn't mean to find himself half a world away in a hostile city, but that's where he ends up. When some children trip the booby traps in a stairwell, the soldiers have to get out of the city. However, their van has been stolen and thing go wrong with the extraction, the way things in war so often do. The difficulty is not in getting in, it's in getting out. The parallels to the quagmire in Iraq are so obvious they defy mention. The result is a haunting, minimalist work painted in surreal shades of desert brown. It echoes "A Farewell to Arms" and "Dog Soldiers" yet remains unique to the new millennium. Eck writes:

The Humvee's engine finally cut off and the vehicle slowed until we rolled to a stop.

"He's dead," said Santiago.

"I know." I stepped out of the Humvee.

I saw two adults and a child approaching us in the distance. It must have been a family.

I tossed my helmet into the driver's seat and picked up my 9mm. Sand was blowing in off the desert. I stood there leaning against the hood of the Humvee, the 9mm at my side.

None of the soldiers are heroes, but they're not villains either. They are not always sure of their targets and they make bad decisions, more circumstantial than not. Some of them don't make it out, but their death is as random as their cause.

The writing is often beautiful. And modern war has probably never been so fully explored as in this small, relentless novel. Eck never panders. We are not asked to cry, only to go quietly along for the ride.

The army was out there too, massing to the southwest and the northeast, along the main road that ran down the coast and through the city. We were to gauge the show of force against the level of resistance and report on whether the city was awed enough to accept help in forming some kind of government.

This near-perfect book is published by Milkweed Press Editions, a small publisher in Minnesota. Possibly the first great war novel of our generation, "The Farther Shore" will easily be one of the best novels of the year. But the question is, does anybody care? Thirty-five years ago, Nick Ut took a picture of a naked girl burned by napalm running crying down the street in Vietnam. That picture helped end a war. Now Nick Ut is taking pictures of Paris Hilton, crying in the police car as she's driven back to jail. Novels, photography and art used to be part of the conversation when contemplating murder and death a world away.

The question of the moment is not why American fiction isn't engaging with the world. It is. The question is why we aren't paying attention.

Shares