For four years, Valerie Plame Wilson has existed for most Americans largely as a one-dimensional figure, a symbol at best. She was a misspelled scrawl -- "Valerie Flame" -- in New York Times reporter Judith Miller's notebook. She was a beautiful woman swathed in shades and scarf in a Vanity Fair photo spread. She was deemed "little more than a glorified secretary" by a Republican congressman, trying to defuse growing suspicion that her outing as a CIA covert operative, by someone high up in the Bush administration, had been an illegal breach of national security. By the left, she and her husband, former ambassador and weapons of mass destruction whistle-blower Joe Wilson, were lionized as martyrs to the antiwar cause.

But whether people saw her as a scribbled name or a glossy Mata Hari, a secretary or a Joan of Arc, it's safe to say that until recently, she was an entirely mute specter. Plame has spent years in a state of enforced verbal paralysis, forbidden from telling her own story thanks to her employment at the Central Intelligence Agency, but batted around by every Bob, Dick and Scooter who could get their claws into her.

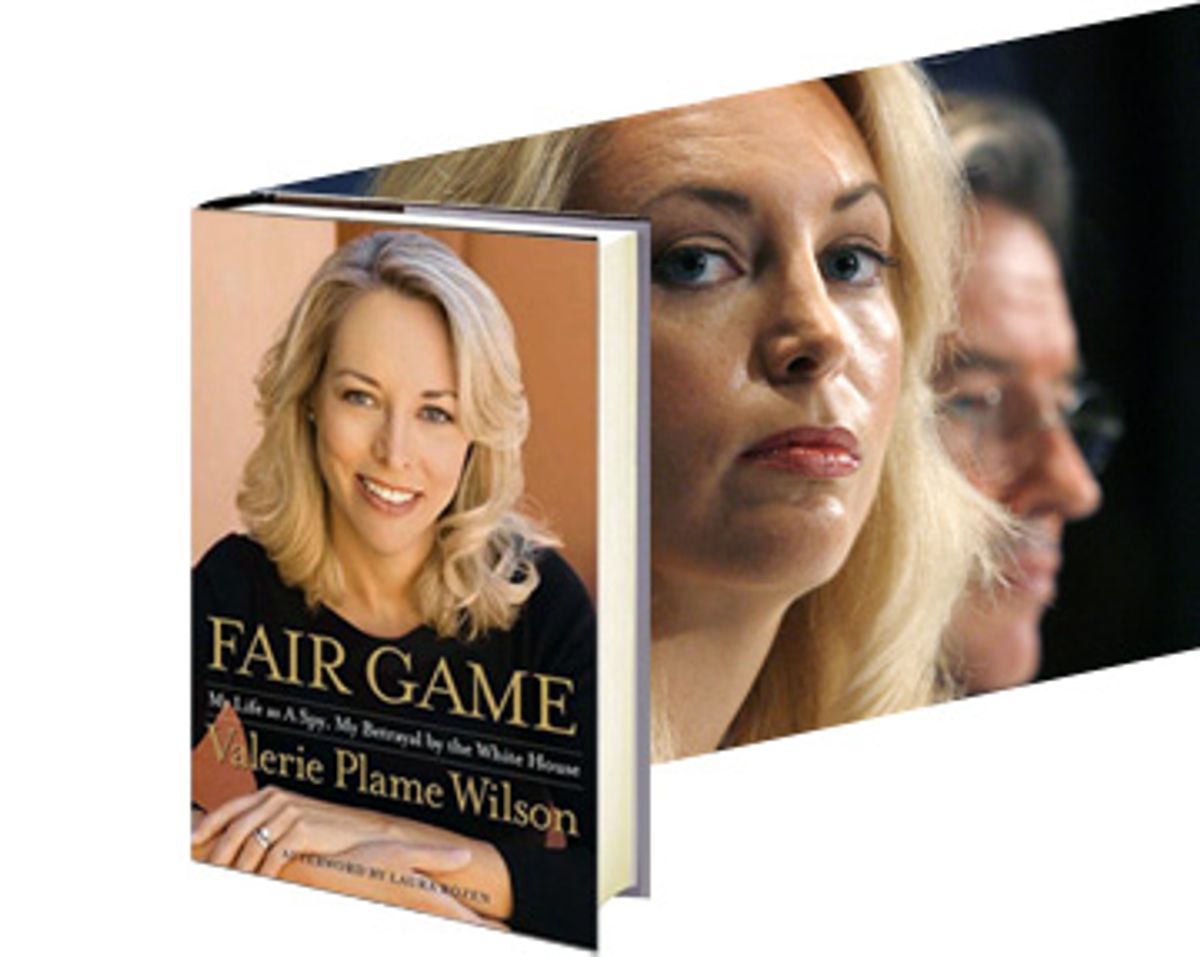

With her book "Fair Game: My Life as a Spy, My Betrayal by the White House," published this week by Simon and Schuster, Plame is finally gaining her voice -- sort of. Forced to submit her manuscript to the CIA, an organization not widely known for its high regard for freedom of expression, Plame was told to remove all references to dates and details of her employment, dates and details that had already been made public elsewhere, including by the CIA itself in a 2006 unclassified letter. Plame and her publishers sued but lost and, instead of rewriting around the redactions, decided to include them. The book is riddled with gray bars that make the narrative frequently unintelligible.

The most disconcerting instance occurs at the juncture at which she apparently first encounters Wilson, soon after her return from a tour in Europe. After two pages of blacked-out text there is a perplexing paragraph about a lady pushing two pugs in a stroller. Another paragraph is redacted, and then comes the sentence "Joe and I were immediately consumed by our respective responsibilities." She has apparently met her future husband, but forget the wine and roses and violins -- we don't even know how or when or under what circumstances. Two more pages of redacted text end the chapter. The next begins with the birth of their twins. Readers learn nothing of the couple's initial interaction, courtship or wedding.

It's a shocking vision of what a life can look like when its narration is taken out of the hands of the person living it. Plame's love life, her marriage, her personal chronology ... apparently, these do not belong to her but to her former employer. Without their permission, she has no rights to them.

Plame's choice to include every bit of the redactions is a natural rebellious response, though it also means that in places, "Fair Game" makes its points as a kind of installation art, rather than as a readable book. (It is also a staggering waste of paper.) An afterword by reporter Laura Rozen, filling in some of the blanks of Plame's career based on sources already in the public record, is tacked on as a reference that helps a bit in deciphering her tale.

Because much of what Plame has, silently, come to stand for is what your country is not supposed to do to you -- sell you out, betray your years of service, leave you vulnerable to attack -- she has competing missions in this book. She must delineate the ways in which she has been buffeted by the gales of right-wing ideology, but also raise her voice and present her bona fides as a patriot, a professional, an actual undercover spy whose identity was a matter of national security and an American citizen who was ill-used. In short, Plame must justify her own life and work to a readership that has been manipulated into questioning her credentials so that they can better understand what happened to her.

The first thing that Valerie Plame would like you to know about her is that she is a badass.

She begins her story not with her suburban childhood (except for a few photos of herself as a kid, most in prescient spy-lady locations, like the cockpit of a small plane or traveling in Europe, she barely acknowledges her pre-CIA life) but with a sweaty escape and invasion exercise with helicopters at the CIA training "Farm."

The early passages in the book, in which she chronicles tests of physical and mental endurance at the hands of her agency instructors, read like a fun Bond novel, in which it's clear that the heroine is one hell of a brassy dame. Plame crows about being light enough to land on her feet and remain standing after a parachute jump, about another female trainee who was "not a nemesis per se, but [whose] superior airs got my competitive spirit going," and with coy glee about answering a hypothetical question about how to avoid suspicion if caught with a male spy in a hotel room: She tells her examiner that she would simply remove her shirt and get into bed with him. When she senses that she has answered correctly, she practically purrs, "This could be fun."

In her late 20s, Plame is sent on a foreign tour to a redacted location (also known as Athens). There she whoops it up, looking down her nose at female colleagues too lily-livered to withstand ogling from the "dinosaur" higher-ups, and at the "weak" American families who gather at hamburger huts complaining about homesickness instead of enjoying their foreign adventures. Plame is proud of her zero-tolerance policy toward weakness. When she writes later about living through months of agonizing postpartum depression after the birth of her twins, she confesses that finally telling someone she wasn't feeling up to snuff was "a huge admission for me."

It's after the birth of her kids that Plame is able to lay off the spunkiness and begin to present her credentials as an objective voice on international terrorism. She returns to work at the counterproliferation division (CPD), whose interests included weapon procurement networks in the Middle East. "Four years after the invasion of Iraq ... it is easy to surrender to a revisionist idea that all the WMD evidence against Iraq was fabricated," writes Plame, making the case that she did not go into her work convinced that Iraq's weaponry potential was nonexistent. "While it is true that powerful ideologues encouraged a war to prove their own geopolitical theories, and critical failures of judgment were made throughout the intelligence community in the spring and summer of 2002, Iraq, under its cruel dictator Saddam Hussein, was clearly a rogue nation that flouted international treaties and norms in its quest for regional superiority."

Plame also must make clear that in response to an unusual response from the office of Vice President Cheney that the CIA investigate a report that in 1999 Iraq sought yellowcake uranium from Niger, she did not put her husband up for the job. The idea, Plame reports, was first brought up by "a midlevel reports officer" in a hallway conversation about how to respond to the vice president's office's query.

This is a critical point, given the assertions by those who sought to undermine the Wilsons that Plame herself suggested sending her husband to Niger, or that his mission was the result of nepotism. She returns to it often and perhaps protests too much. Not because she's not correct but because it shouldn't matter. Wilson went to Niger; he found no evidence that Iraq could have obtained uranium there; he reported his findings; the White House disregarded them; Wilson wrote about that; and the White House retaliated against his family, compromising national security in the process. Then the president lied about the consequences for those who leaked information. To fret about whose idea it was that Wilson travel to Africa is to miss the forest for a tree in a neighboring meadow. But for the record, here is Plame's repeated avowal: Not. Her. Idea.

While performing the required elements of her self-justification routine (between the gray bars of redaction), Plame pulls off one trick with particular aplomb. Her descriptions of the ways this national saga played out in her household are very funny, and Plame makes an excellent Jane Bond, double-stroller pusher, while painting a compelling portrait of life as a woman in a mostly male institution.

In one paragraph, she writes, "In CPD's Iraq branch, the job [REDACTED] was to figure out how to mount the operations that would produce credible intelligence on suspected Iraqi WMD programs." In the next paragraph, she reveals, "I found that if I gave Samantha Magic Markers and paper, and Trevor some special snacks, I could buy myself about thirty minutes to draft some cables out to the field." She also gamely reports that her only trepidation about her husband's trip to Niger was her fear of being "left to wrestle two squirmy toddlers into bed each evening."

Plame describes Wilson's return from his nine-day mission -- in which he found no evidence of missing uranium -- as uneventful. After hugging his kids, he was greeted by CIA officers, and then they all ate Chinese food. "I wish I had saved the fortune cookies from that night," writes Plame. "There was, of course, no inkling of the scandal that Joe's trip would ignite. Both of us felt that we were doing our jobs and serving our country."

It's at this somewhat flat moment that Plame's narrative must take its sharp turn. After Wilson's report on Niger, events render this active couple oddly passive, and Plame's story becomes dreamlike as she watches the world around her tip off its axis.

Plame describes listening to Bush's State of the Union address, in which he uttered the 16 words -- that "the British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa" --that seemed to contradict the evidence Wilson had dropped at the feet of the administration.

After Colin Powell's presentation to the United Nations, Plame recalls drifting from the television set, experiencing "cognitive dissonance" between what she knows to be the state of intelligence on WMD and what is being shown on television. "It wasn't that the evidence [Powell] was citing had no factual basis," she writes, "but our intelligence had so many caveats and questions that his conclusions, at minimum, seemed too optimistic and almost glib ... he had used only the most sensational and tantalizing bits ... without any of those appropriate caveats or cautions."

Plame was shocked at the way nuanced, complex truths were being steamrollered by ideology on the inevitable road to war. "The idea that my government, which I had served loyally for years, might be exaggerating a case for war was impossible to comprehend," she writes. "Nothing made sense."

Plame claims she is no "starry-eyed idealist," but retrospectively, some of her assertions about being stunned by government manipulation seem naive to the point of incredulity, coming from a woman who worked at the CIA for 20 years. "At no time did Joe or I ever consider that my cover and work at the CIA would be compromised by his submission of the ["What I Didn't Find in Africa"] op-ed," she writes.

And perhaps it's only the intervening years that keep that from ringing quite true. Time, and the Bush administration, made cynics of us all. If it's hard to believe now that an investigation that didn't turn up the WMD evidence the administration desired might result in retaliation against the investigator's WMD-searching wife, then it's probably because in America, it really shouldn't have.

From here on out, Plame tells a story that most of us have already heard, but this time from her perspective. She dutifully chronicles the slow-motion events leading to her exposure, from columnist Robert Novak's comment that "Wilson's an asshole. The CIA sent him [to Niger]. His wife, Valerie, works for the CIA" to her increasing sense of foreboding as she visits the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago with her kids, a satisfyingly sharky set-up for a woman days away from getting chomped.

Less than a week later, Wilson walks into their bedroom, throws the Washington Post on the bed and announces, "Well, the SOB did it." Plame writes that she read Novak's column, in which she was named as "Valerie Plame, an Agency operative on weapons of mass destruction," and that "the words were right there in black and white, but I could not take them in. I felt like I had been sucker-punched, hard, in the gut." She drops the paper to the floor before beginning to do mental math equations: How many of her associates would be put in danger? How wide was the Post's circulation? What was the security risk to her family?

Plame's feelings of isolation and humiliation are palpable in her description of the weeks following her outing. Inconveniently trapped in a weeklong management seminar, she feels cut off from work; neighbors voice surprise at her secret identity; a colleague weakly assures her it will blow over.

These anecdotes are part of what "Fair Game" does best: remind us that besides being a political hockey puck, Plame is a human being. It's around this time that Karl Rove tells Chris Matthews that Plame's name and identity are "fair game."

Plame compares the attacks on her husband that followed her outing to the Swift-boating of John Kerry. "Fearmongering, defamation of character, shameless disregard for truth, and distortions of reality. It was classic Karl Rove," she writes. As Wilson's business partners are pressured to cut off contact with him, she describes "the new Orwellian world that we inhabited," in which she is so anxiety-stricken that she finds herself an "incredibly stressed and impatient mother" who yells at her kids "like a fishwife" when they refuse to take a bath. The phone never stopped ringing with long-lost friends and rubberneckers; she started smoking again to combat the anxiety; her marriage suffered. (Plame even writes that she and Wilson decided "this must be the only Washington scandal ever without sex -- we were just too exhausted.")

Also miserable at the office, Plame describes the trouble she has justifying "sending young and inadequately trained CIA officers [to Baghdad] to deal with the volatile insurgency so they could continue the elusive 'hunt for WMDs' ... Our policies at every level seemed ineffective and everyone in my chain of command appeared paralyzed, unable to come to grips with the reality on the ground in Iraq. I could barely breathe. There was no relief at home or work." In August 2004, Plame takes leave without pay and heads home to deal with her marriage, which is crumbling in part because of her husband's belief that while he had defended her valiantly, she never stepped up on his behalf. Here, too, Plame, of the once boundless ambition and vigor, is hamstrung: How was she to defend him when, as a CIA employee, she had not been permitted to speak to the press?

"Fair Game" tells a very ugly story, one that does not flatter anyone -- not even, sometimes, its subject. Plame is a tough character, and there are many instances in which she seems to want things both ways: to be surprised at the affronts to her manuscript enacted by the fascistic CIA, and to convince us of her career-long loyalty to that agency, with whose fascistic tendencies she had presumably been familiar. Plame needs to demonstrate that she has balls of steel -- and she does! -- but often reminds readers of her girlishness to sometimes horrifying effect, as when she explains how she was extra-prepared for CIA work after her experiences during Pi Phi rush at Penn State. (Oh yes she did.)

She also wants us to believe that her privacy and anonymity were of utmost importance to her, and also explain how, exactly, she wound up looking like Ingrid Bergman in the pages of Vanity Fair.

This point remains one of the touchiest for Plame. As she describes the publicity following her outing, she recalls relief at the fact that a New York Times profile did not include a photo. "I at least could still shop at Safeway ... without enduring whispers and glances," she writes, bemoaning that "this instantaneous shift to being a public persona brought great anxiety ... It didn't matter that most of the press attention was positive; all of it seemed intrusive, and I didn't want any part of it." Until, nine pages later, she comes home to find a photo crew in her kitchen, setting up to snap her husband for an extensive interview he'd given Vanity Fair.

Plame writes that "the Vanity Fair team turned as if one and beseeched me to consider getting my photo taken as well." They beseeched her, OK? She continues, "Caught up in the glamorous moment and feeling somewhat beaten down, I reluctantly agreed, but only if I could not be recognized." Plame self-flagellates and finally gives in: "I did not listen to my instincts and threw my extreme caution about public exposure to the wind." And that's the story of how she accidentally wound up in shades and a scarf, sitting in the front seat of a Jaguar, parked outside the White House, for a big fat photo spread. Whoops!

Plame got reamed for this move by a right wing eager to jump up and down, point their fingers and accuse her of outing herself, and by her CIA boss, who was understandably ticked that his operative had chosen to make her pictorial debut without informing him. "I have never been spoken to so harshly by a supervisor," writes Plame, who concedes that her boss was right, before classily revealing that he'd been having an affair with someone in his direct chain of command at the time.

But if Plame is not someone you'd necessarily seek out as, say, a sorority sister, that's OK. It's probably a rare person who zips around the globe as a spy, gets royally screwed by the government to which she has devoted her career, and manages to get up as soon as she's legally allowed and punch them in the nose. She might not be your ideal wingwoman, but she's a pretty remarkable American.

Shares