One afternoon when I was about 8 years old, I sat watching TV in the family room as a weekend horror matinee came on. The movie, "House of a Thousand Screams," began, if I remember correctly, with the shadow of a cackling witch inching along a wall and a closet full of chains and blood. My father, who happened to be passing by at that moment, walked across the room and snapped off the TV. "You're not watching that," he said.

Dad wasn't a particularly patronizing or censorious parent; I remember him trying to explain Bob Dylan lyrics to me at an age when I was much too young to comprehend lines like, "She takes just like a woman, but she breaks like a little girl" -- an ominous remark, if you happen to be an actual little girl. He wasn't afraid I'd grow up to be a homicidal maniac as a result of watching "House of a Thousand Screams"; he just didn't want me to have nightmares. This was a well-placed fear; even when I grew older, similar stuff would keep me up late, staring into the dark corners of my room.

I tell this story not because it's remarkable, but because it's so ordinary, an example of a parent doing something we'd all like to think parents do: exercise judgment over the entertainment their kids consume in situations where kids can't necessarily be trusted to know what's best. Just about everyone who, like myself, values freedom of expression and wants to minimize a priori censorship has at least once insisted that parents should take responsibility for their kids' media diet, rather than demanding that certain subject matter or imagery be removed from popular culture entirely. Whether it's TV or movies, the Internet or video games, parental vigilance is, in a way, a linchpin to safeguarding the marketplace of ideas.

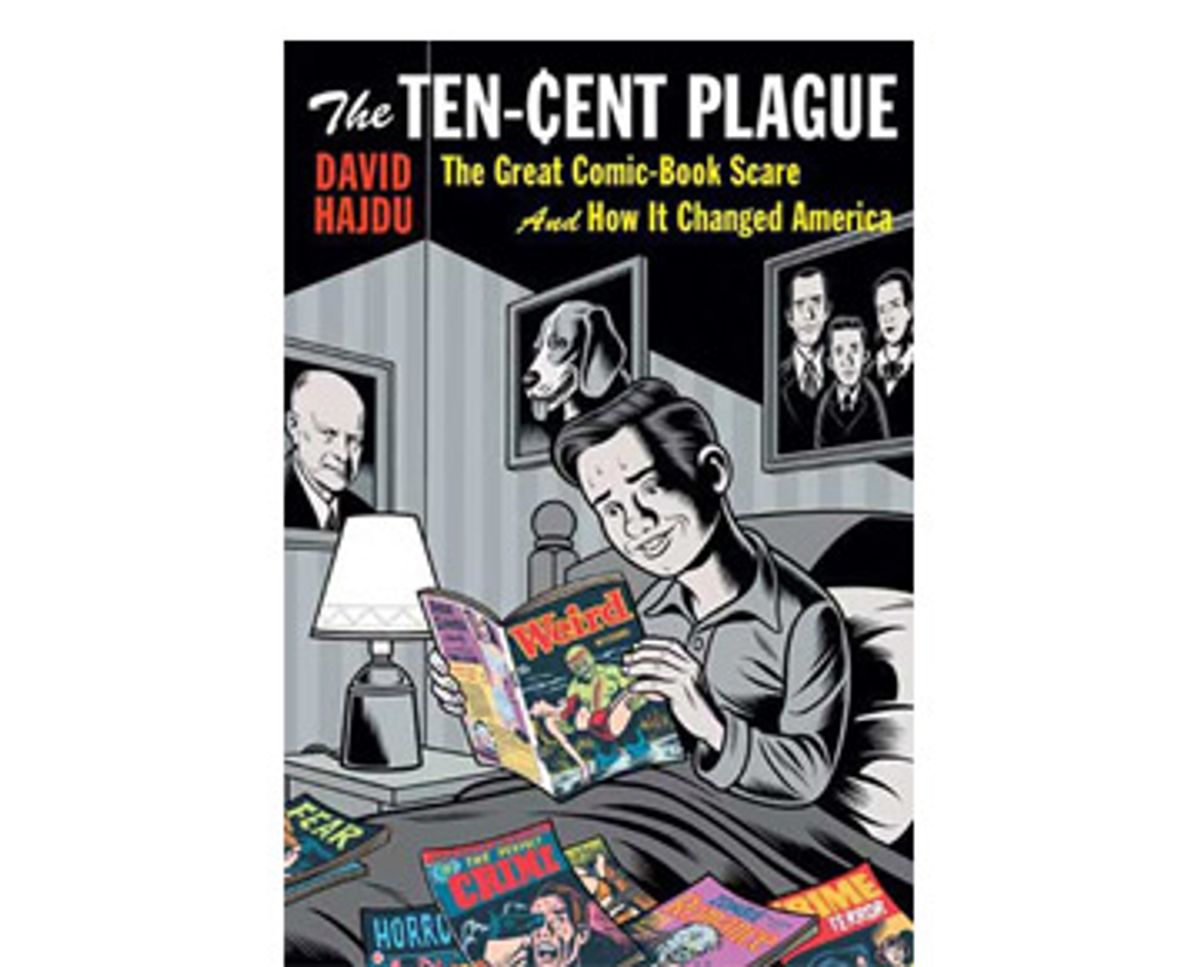

The comic book panic of the 1950s was neither the first nor the last occasion when anxieties about children's exposure to American pop culture got out of hand. Anthony Comstock fulminated against dime novels in the 19th century and the government continues to battle federal court judges over the enforcement of the Child Online Protection Act in this one. According to David Hajdu, author of "The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America," the attack on comic books -- culminating in a sensational televised congressional committee hearing in 1954 -- is particularly important because it marks the birth of the rebellious youth culture of the 1960s. It was over the issue of comics, he argues, that the generation gap first emerged.

"The Ten-Cent Plague" is partly a history of mid-20th century comics and the people who made them, an amusing assortment of eccentrics, hustlers and dreamers. Charles Biro invented the crime comic book -- his brainchild, "Crime Does Not Pay," displayed the word "Crime" in cover type eight times bigger than "Does Not Pay," and ran stories like "The Mad Musician and His Tunes of Doom" and "The Wild Spree of the Laughing Sadist -- Herman Duker" -- and he kept a monkey who sat on his shoulder while he drew. "I always looked for that monkey," one of his former employees told Hajdu. "If he was sitting there like a nice monkey, that meant Charlie was happy. If he was nervous, that meant there was trouble."

Then there was the breathtakingly mercenary publisher Victor Fox, whose writers had to beg to get paid and usually got bad checks, a man who "never meant a word he said," according to one source. Stanley P. Morse put out comic books with stories titled simply "Hate" or "Violence" and once remarked, "I don't know what the hell I published. I never knew. I never read the things. I never cared."

Hajdu, who wrote "Positively 4th Street," an acclaimed history of the folk music movement in New York, also includes sensitive souls like Will Eisner, creator of the seminal series "The Spirit," who bemoaned the lack of "intellectual criticism of comic books" despite the presence of writers and artists "who were very creative and serious about what they were doing." Others among his colleagues were solid artisans who found fulfillment in comic books after being rejected by more respectable industries because of their race, ethnicity, religion or gender -- like Janice Valleau, who got a kick out of drawing Toni Gayle, a fashion model who solved crimes in her spare time. Still others found the form an outlet for unconventional inclinations; William Moulton Marston's Wonder Woman, with her "bracelets of submission," allowed her creator to explore what he declared to be "the subconscious, elaborately disguised desire of males to be mastered by a woman who loves them."

At the center of the scandal, however, was William M. Gaines, a high school science teacher who was obliged to take up the reins at EC Comics when his father died in a boating accident in 1947. Gaines claimed (inaccurately, as Hajdu demonstrates) to have originated the horror comic genre, which, with the crime and romance comics of the time, became a particular target of crusaders. Unlike Fox and Morse, Gaines paid his contributors fairly well and believed that his product had cultural value. He didn't just read them, he helped write them, cooking up story ideas for books like "The Vault of Horror" and "Tales From the Crypt" during Dexedrine-fueled all-night binges spent poring over "every science fiction and horror story I could get my hands on."

Gaines' nemesis was the psychiatrist Frederic Wertham, whose inflammatory 1954 book, "The Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today's Youth," made him the most prominent among the multiplying ranks of anti-comics activists in the early 1950s. Both men testified before the Senate subcommittee on juvenile delinquency in April 1954. Wertham wantonly characterized all comics as "crime comics" because all involved imperfect obedience to one code or another, whether legal or moral. (Superman was a vigilante and the love-struck heroines of romance comics often defied their parents.) He also provided no empirical support for his theory that comic books caused delinquency and emotional disturbance -- not beyond highly anecdotal observations gleaned at several centers where he worked with troubled youth. As Hajdu points out, Wertham discovered that most of these kids read comic books because most kids at that time read comic books, whether they were troubled or not.

Gaines' testimony at the hearing was a disaster, in part because he'd stayed up all night planning it and didn't get to speak until the speed was wearing off. Across the country, lawmakers were passing bills to restrict or eradicate the distribution of comic books, and community groups organized mass burnings. The reviews of Wertham's book were largely uncritical and admiring, despite his bizarre fixation on superheroes and their purported connection to the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche and, by extension, Nazism. The press fanned the frenzy by running headlines like "Depravity for Children -- 10 Cents a Copy," which was published above the logotype of the Hartford Courant, according to Hajdu, "a step unprecedented in the Courant's 190-year history." The comic book problem was apparently bigger news than Pearl Harbor.

In a last-ditch effort to save their industry, comic book publishers formed a trade organization, the Comics Magazine Association of America, and a code that Hajdu describes as "a monument to self-imposed repression and prudery." A few, including Gaines, decided they couldn't produce any comics of worth or commercial appeal under the code, but without the CMAA's seal of approval, renegade comic books wouldn't get picked up by distributors and newsstand proprietors who'd been spooked by the controversy. Many of the artists and writers abandoned creative professions entirely to work as security guards and mailmen, and Gaines discontinued every title he put out -- except Mad, which he published as a magazine (thereby eluding CMAA jurisdiction).

The lineaments of this story are fairly familiar, despite Hajdu's insistence in the introduction to "The Ten-Cent Plague" that it has become "a largely forgotten chapter in the history of the culture wars." A fresher observation is that comics, not rock 'n' roll, were an intimation of the "postwar sensibility" to come, an outlook that was "a raucous and cynical one, inured to violence and absorbed with sex, skeptical of authority, and frozen in childhood." Mad magazine, full of bratty parodies of the products of mainstream culture, has often been cited as the first inkling of that sensibility, and Mad was decidedly born out of the comic book scare. Hajdu illustrates the rebellion simmering within young comics fans with quotes from people who were pressured into participating in comic book burnings as children. "I thought about that bonfire and all those comics and it made me sick," one source told him. "I started to get angry ... and went out and bought myself some comic books."

What "The Ten-Cent Plague" has over any previous treatment of the subject is an impressive depth of research. The disgruntled comics reader quoted above is far from the only ordinary person Hajdu appears to have tracked down from a name in a yellowing newspaper clipping. (He even interviewed the great African-American photographer Gordon Parks, who took Wertham's author photo.) As a story of intergenerational paranoia and censorious media-fueled panic, the comic book scare was a signal moment in postwar American history, the grammar school version of the McCarthy hearings. Yet for all the exhaustive attention Hajdu trains on the subject, he never quite comes to terms with some major questions.

Granted, the anti-comics crusade was hysterical, an out-of-proportion reaction to a manufactured crisis in "juvenile delinquency." (Like the alarmism about child abductions a few years ago, this was largely a matter of people regarding sensational media reports of isolated incidents as indicative of a wider social trend.) The politicians who ran the hearings were grandstanding, Wertham was a peculiar obsessive, and the ensuing crackdown clearly violated the First Amendment in many instances. Still, to a certain extent, the comic book industry dug its own grave. The pivotal moment in Gaines' testimony came when the committee chairman held up a copy of "Crime SuspenStories," featuring a huge close-up of, in Hajdu's words, "the severed head of an attractive blond woman, dangling by the hair in the grip of her killer," with a bloody ax just behind it.

Even if he hadn't been collapsing from exhaustion, it's difficult to see how Gaines could have defended this and other comic vignettes -- a baseball game played with dismembered body parts and a woman roasting her husband's corpse on the backyard grill -- as appropriate for children. Still, Hajdu waxes indignant that, as the panic gathered force, "adults did not seem prepared to accept the average young person's capacity for independent thought and discrimination." What he seems unable to acknowledge is that overriding a kid's judgment is part of a parent's job, up to a point. Otherwise, we'd all have grown up on a diet of candy and pizza.

Where that point comes is perhaps the most difficult question to answer. Within the comics industry, people did quarrel over content; EC's longtime business manager quit because he objected to some of what they published. Hajdu himself admits that "if 'Seduction of the Innocent' encouraged some parents to keep copies of Stanley P. Morse's 'Weird Chills' out of third-graders' hands, Wertham performed a worthy service." Some of the era's comic books were a kind of art, but others were produced with the attitude best epitomized by Morse, who once said, "No one complained, so we gave the people what they wanted until they started complaining about it." When a senator at the committee hearings protested that comic book publishers "do not seem to care what they do or what they purvey or what they dish out to these youngsters as long as it sells and brings in the money," he was -- at least partly -- right.

According to Hajdu, Gaines and his committed writers and artists believed their readers to be in their mid- to late teens, but that doesn't mean they did anything to help parents keep 7-year-olds away from their more extreme books. The industry only instituted its code once it was backed into a corner, and then it went predictably overboard. Gaines was pressured to change a science fiction parable about racial discrimination because the code's administrator declared, nonsensically, "You can't have a Negro."

The clash between the comic book publishers and the anti-comics campaigners was a folie à deux, with neither side showing much willingness to consider the larger consequences of its actions. Comics were an easy target for morals crusaders because their constituency -- children and teenagers -- couldn't stand up for themselves and their rights. On the other hand, some comics publishers really had abused the naive faith of American parents who assumed that their fellow citizens wouldn't seek profits by introducing their kids to dismemberment and cannibalism behind their backs. If the greater wrong lies with the censors, both sides sought advantage in the fact that nobody took children's culture seriously.

Hajdu, however, is determined to paint comic book publishers as martyrs (if sometimes sleazy ones) and their foes as crazed, ignorant, snobby prudes. Idealizing the underdog in this case is essential to the heroic narrative embedded in "The Ten-Cent Plague," to its celebration of the comics as a defiant voice in a conformist 1950s society that reflexively kowtowed to authority and institutions. The problem, as the counterculture would eventually demonstrate, is that while authority isn't always right, it isn't always wrong, either. Knee-jerk rebellion can be as stupid as knee-jerk obedience. Just think how differently the sorry tale of the great comic book scare would have turned out if everyone involved had been a little more grown-up.

Shares