"Oh Lavinia," says the ghost of a poet to the title character of Ursula K. Le Guin's new novel, "Lavinia," "You are worth ten Camillas. And I never saw it."

The ghost is Virgil, the great Latin poet whose masterpiece, the Aeneid, tells of the founding of Rome by Aeneas, a Trojan rendered homeless by the fall of his city to the Greeks. Lavinia -- daughter of Latinus, king of the Latins -- marries Aeneas at the end of his wanderings, but their wedding isn't depicted in the Aeneid; Virgil died before he could finish the poem. Instead, the last scene ends in war, with Aeneas killing the prince of a neighboring tribe and a rival for Lavinia's hand. (Camilla, an Amazon-like warrior queen, is another heroic casualty in the battle over who will rule the Latins.) Of Lavinia herself, the real Virgil wrote only that she blushed (as befitted a virtuous maiden) when her wedding was discussed. She never gets to say a single word.

Lavinia makes for an unlikely heroine, which is just what Le Guin likes about her. From Mulan to Buffy the Vampire Slayer, sassy, kick-ass girls are preferred nowadays to circumspect homebodies like Virgil's Latin princess. There may even be a touch of self-reproach in Le Guin's choice of Lavinia as her main character, since the heroine of her 1971 novel, "The Tombs of Atuan," is a priestess named Tenar who rebels against a life entirely devoted to serving a pantheon of nameless, implacable gods. Lavinia, by contrast, embraces the ritual aspect of her designated role, all the humble and solemn daily sacrifices, the scattering of sacred salt, the tending of clan totems, and even her own fate, as a woman destined to have little choice in who her husband will be.

In addition to not being one of those books in which a spunky young tomboy learns to kick-box and wield a sword, "Lavinia" is also not a revisionist fiction in which a minor character from a famous book (Mr. Rochester's wife or Dr. Jekyll's maid, for example) finally gets to correct the official record. Le Guin clearly loves Virgil and the "essentially untranslatable" beauty of his verse, and so does her heroine, who gets a chance to hear the latter when the poet's shade appears to her during a pilgrimage to a sacred grove. Aware of her fictionality (all of the characters in the "Aeneid" are derived from old legends but are otherwise inventions of Virgil, although only Lavinia realizes this), she sees her own tale as the completion of her creator's work, a subject that (in this telling at least) he regretted not getting the chance to explore before his death. "I'm not sure of the nature of my existence," Lavinia explains. "As far as I know, it was my poet who gave me any reality at all." Perhaps "the events I remember only come to exist as I write them, or as he wrote them."

Not much of "Lavinia" is devoted to its main character's hazy ontological status: just enough to let you know that Le Guin is imagining someone else's imagining of an imaginary woman. In other words: This is not history, or anything like it. That said, the setting and action are otherwise realistic. The novel's true business is to serve as a tribute to a relatively uncelebrated culture, that of "early Rome: a forum not of marble but of wood and brick, an austere people with a strong sense of duty, order and justice" whom Le Guin admires for their cherishing of "certain homely but delicate values, such as the loyalty, modesty and responsibility implicit in Virgil's idea of a hero."

Against all odds, in this age of flashy, bold and individualistic protagonists, Le Guin's Lavinia feels paradoxically tranquil and vivid. Devoted to her father, who shares her love of "the ever-recurring rituals," she must get by without the love of her mother, Amata, who has never forgiven Lavinia for surviving the epidemic that claimed her two sons. The drama of the novel hinges on Amata's mad determination that her daughter marry Turnus -- her nephew, a replacement for her lost sons and perhaps the object of less acceptable yearnings as well. An oracle tells Latinus that he must marry his daughter to a foreigner, and when Aeneas and his Trojans arrive, it is obvious to everyone but Amata who the bridegroom should be. Le Guin's Aeneas is Virgil's: an impressive man of honor and courage whose commitment to duty often requires him to conquer his own heart. War breaks out when the bellicose, strutting Turnus vows to defy Latinus' wishes.

As for Lavinia, though no one (besides her father) takes her personal wishes much into account, she distrusts Turnus from the beginning; he lacks Aeneas' great quality, his "piety." When she is promised to the Trojan, she feels not love (as she's never really met Aeneas), but a transcendent sense of destiny. "To hear myself promised as part of a treaty, exchanged like a cup or a piece of clothing, might seem as deep an insult as could be offered to a human soul," she observes, but her betrothal leaves her paradoxically liberated. "I felt the same certainty I had seen in my father's eyes. Things were going as they should go, and in going with them I was free." The restraints of "religion and my duty to my people," bonds that Le Guin's earlier character, Tenar, found oppressive, are for Lavinia "part of me, not external, not enslaving; rather, in enlarging the scope of my soul and mind, they liberated me from the narrowness of the single self."

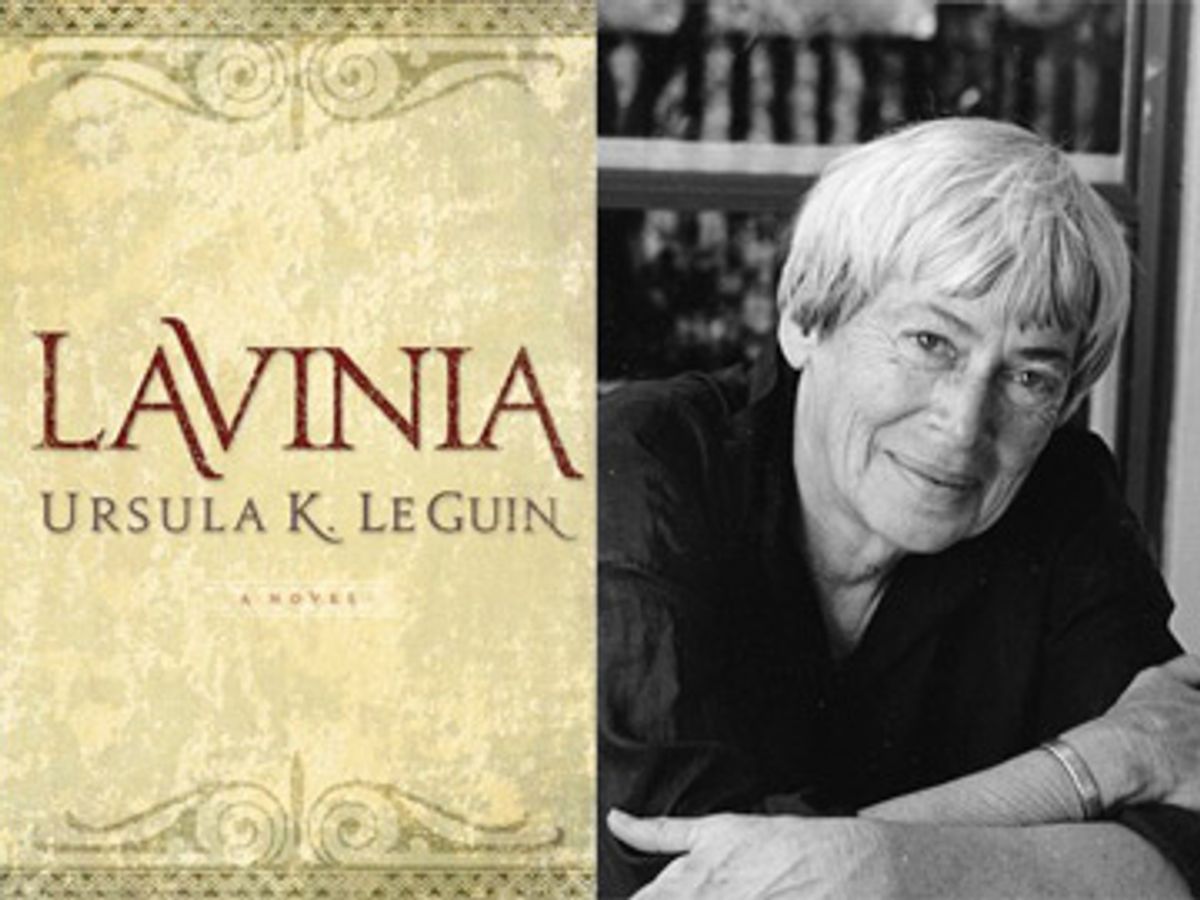

"Lavinia" is an old writer's book -- Le Guin is 79 -- in the best sense of the word; it is ripe with that half-remembered virtue, wisdom. This, Le Guin seems to be saying, is what it feels like to be the personification of your land and your people, to speak the words and perform the rites of "the old, local, earth-deep religion," to be the sacred guardian of harmony and plenty for a handful of rustic villages and farms, and to carry their past and future in your body. It's not a life any of us know how to live anymore, and most likely not one that most of us would choose, but some of us can still imagine it, and imagine that it was good.

Shares