Between Ronald Reagan's last year of presidential office in 1989 and his death in 2004, a strange transformation took place within the Washington Post. I only noticed when, in a fit of masochism, I began to plow through the paper's coverage of Reagan's state funeral. As expected, there were the usual encomiums from Krauthammer and Will and Novak -- no different in kind than what they'd been churning out for a quarter-century -- but where was the other side? After decades of antagonism to Republican presidents in general and Reagan in particular, Post reporters, analysts, columnists and editorialists were sprinting -- practically elbowing each other out of the way -- to apotheosize a man they had never even liked, let alone endorsed.

I finally had to call my brother in Chicago and ask: "When did Reagan stop sucking?"

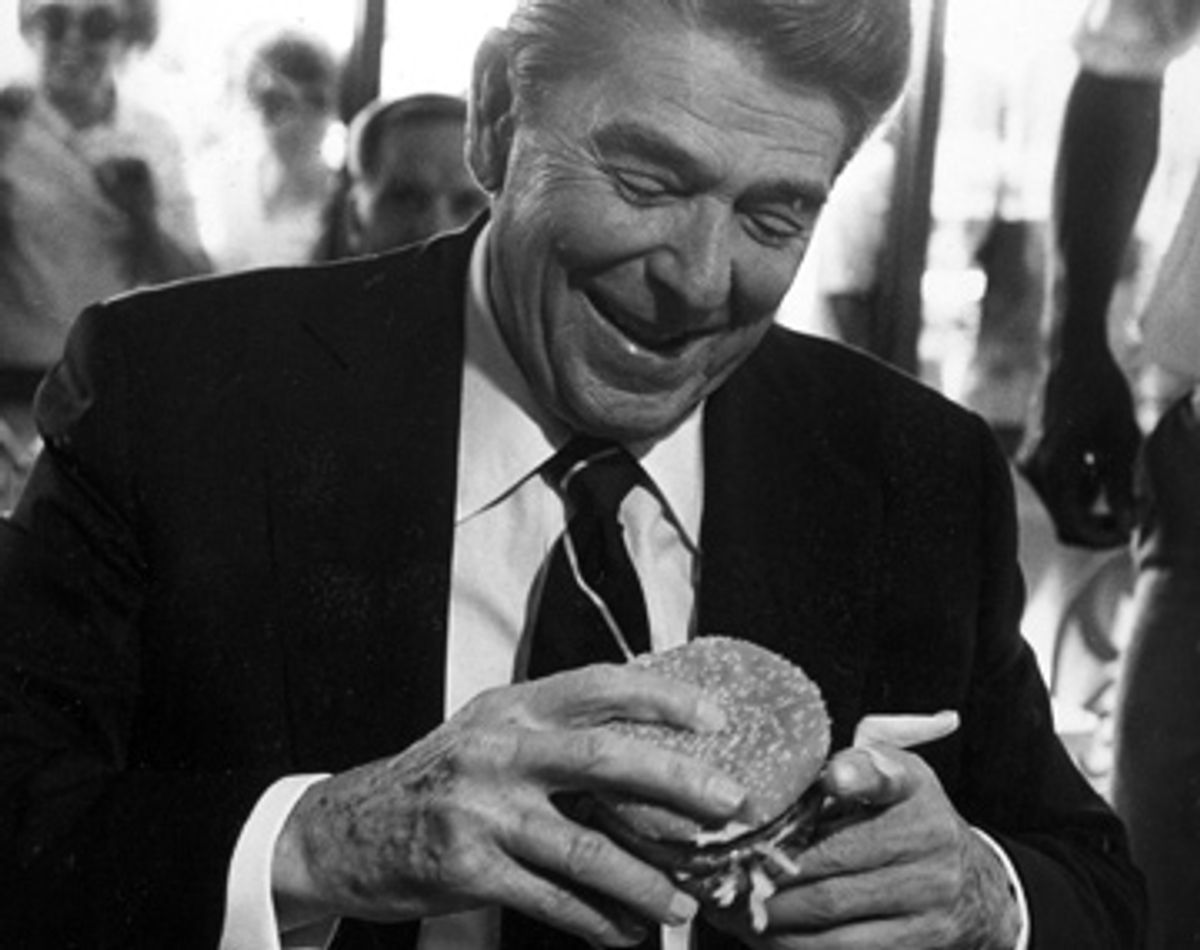

Nostalgia lies so thickly over the '80s that it's hard now to recall what Ronald W. Reagan represented to your average card-carrying liberal. Hating him then was as much an article of faith as hating George W. Bush is now. Everything his supporters loved --the Plexiglas optimism, the blithe disregard for detail, the chuckle, the very cock of his head -- we loathed. To this day, many of my friends refuse to call National Airport by its new title, and to this day, I refuse to pass the Ronald Reagan Building without a private snigger that Mr. Government-Off-Our-Backs has his name forever attached to a massive concrete bureaucratic complex.

But who's sniggering now? History, it seems, is on the side of the turncoat Washington Post, and there's a distinct possibility that if we paleo-libs continue in our ancient rancors, we'll start looking like those troglodytes who still plump for Alger Hiss' innocence. We may finally have to admit that Ronald Reagan didn't ... completely ... in every respect ... suck.

And to guide us down this road of pain, we have liberal historian Sean Wilentz, whose latest volume bears the ominous title "The Age of Reagan: 1974-2008." As in what we've been living through since 1974. As in what is only now just ending. As in how did this happen?

Wilentz's book is couched not as polemic or reportage but as history. Right upfront, he announces he has little in the way of new information to bring to the subject. (Official documents from the Reagan White House are still in short supply.) He acknowledges his own distaste for interviewing, which inevitably co-opts the historian and also takes a really long time. For nearly half the book, Reagan drops out altogether as Wilentz picks over the old scabs of healthcare reform and Monica Lewinsky and the 2000 election dispute -- stuff that doesn't have much if anything to do with the author's nominal subject. The resulting volume is pretty much a survey course in current and not-so-current events, and the response of anyone who actually lived through those years will not be "Really?" but "Oh, yeah, I remember." Phyllis Schlafly ... Ed Meese ... remind me who the hell William French Smith was again?

Whatever news value adheres to this book, then, has little to do with its contents and much to do with its author. Sean Wilentz is the kind of liberal scholar who, when I was attending his lectures more than 20 years ago, could be counted on to jab the Reagan administration every chance he got. As recently as 2006, in a Rolling Stone article, he was making the case that the current Republican president is the worst in history. He's a contributing editor to the New Republic and a Clinton family friend -- an ardent Hillary booster in Salon and elsewhere -- and probably his most enduring sentence came during the 1998 impeachment hearings, when he warned the Republicans howling for Bill Clinton's blood that "history will track you down and condemn you for your cravenness."

The record is clear: Sean Wilentz is no Peggy Noonan. But now, summoned before his own tribunal of history, he matter-of-factly writes: "If greatness in a president is measured in terms of affecting the temper of the times, whether you like it or not, Reagan stands second to none among the presidents of the second half of the twentieth century."

Thanks to the Great Communicator, propositions that were considered extreme 30 years ago -- lowering taxes on the rich, shrinking the domestic safety net, prying people off welfare rolls -- are now so entrenched as to be conventional wisdom. Reagan, more than any conservative reformer before him, succeeded in "redefining the politics of his era and in reshaping the basic terms on which politics and government could be conducted long after he left office. Add in Reagan's remarkable turnabout in helping to end the cold war, as well as his success, albeit easily exaggerated, in uplifting the country after the disaster in Vietnam and the Carter years, and his achievement actually looks more substantial than the claims invented by the Reaganite mythmakers."

And he's still, in some sense, with us. By Wilentz's reckoning, the Reagan era has lasted longer than "the ages of Jefferson and Jackson; longer than the 'gilded' age or the Progressive era; and virtually as long as the combined era of the New Deal, Fair Deal, New Frontier, and Great Society." Which means that the GOP's happiest warrior can now be spoken of in the same breath as Jefferson and Jackson, as Lincoln and the Roosevelts.

Barack Obama, of course, made a much more moderate claim on Reagan's behalf and got his ears boxed by Wilentz's pals, the Clintons. And in truth, Wilentz hasn't forsaken any of his old alliances. Even as he acknowledges Reagan's primacy, he homes in on the gaps between his subject's rhetoric and record. Far from reducing the size of government, for example, Reagan created an upsurge in federal spending relative to gross domestic product. Far from shrinking America's tax burden, he left the percentage of national income diverted to federal taxes virtually unchanged between 1981 and 1989 -- even as states went scrambling to offset cuts in federal assistance. The rich got richer, the poor got poorer, deficits soared to previously unheard-of levels, and the fabled economic recovery that Reagan presided over may now be attributed, Wilentz says, to the stringent interest-rate policies of Fed chair Paul Volcker (first appointed by Carter) and to the steep drop-off in crude oil prices after 1985.

On top of all that, Reagan and his allies nakedly politicized the appointment of federal judges and gutted the enforcement of environmental and civil rights laws. In the battle against AIDS, the most pressing health issue of his presidency, Reagan was a near-complete no-show. (He refused even his own wife's entreaty to endorse the use of condoms.) His record in the developing world wasn't much prettier. "The Reagan Doctrine," writes Wilentz, "contributed to a bloodbath in Central America, where as many as 200,000 people died in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala fighting left-wing regimes or propping up right-wing regimes, with no discernible impact on the outcome of the cold war."

In the end, though, what fascinates Wilentz is not what Reagan did or didn't do but Reaganism itself: "an outgoing, energizing, even sensuous ideal of a bountiful, limitless American future open to everyone who was determined to succeed." Reagan, a former New Deal liberal, managed to co-opt the "bold, unapologetic nationalism" of FDR and John F. Kennedy on behalf of distinctly right-wing causes: paring back government, freeing up corporate enterprise and advancing American might and right, most especially against Communism. What Goldwater began, Reagan finished, and yet he was more than just the sum of his parts. "Reaganism," writes Wilentz, "was its own distinctive blend of dogma, pragmatism, and, above all, mythology. Although it had tens of millions of followers, its theory resided not in a party, a faction, or a movement, but in the mind and persona of one man: Ronald Wilson Reagan."

Which means that it was every bit as complicated -- and perhaps even as illusory -- as the man in question. It becomes even trickier to pin down when you consider Reagan's often-overlooked talent for compromise. Supreme politician that he was, he made a point of courting political foes like Tip O'Neill while keeping his allies on the religious right at something more than arm's length. (Proposed amendments to overturn Roe v. Wade and to legalize school prayer got nowhere on Reagan's watch.) Most crucially, when Mikhail Gorbachev pronounced himself ready to dismantle communism, Reagan took him at his word, ignoring the hawks in his own administration and helping to usher the Cold War toward a peaceful and unimaginably sudden end. "One of the greatest achievements by any president of the United States," Wilentz rightly calls it, "and arguably the greatest single presidential achievement since 1945." And it came about, one could argue, because Reagan knew when to jettison Reaganism.

That lesson in adaptation has been completely lost on Reagan's most obvious heir, George W. Bush, who practices, in Wilentz's words, "a radicalized form of Reaganism," pushing through regressive tax cuts, driving federal deficits to staggering new levels and expanding the police powers of the executive branch to a degree that would make even Nixon blanch. More decisively than Bill Clinton ever could have, Bush has driven the stake through Reaganism's heart -- simply by carrying it to its ultimate conclusion.

If Reaganism really is on the wane, as Wilentz suggests, what exactly have we lost by it? Perhaps the most conspicuously missing item in today's political culture is the thrill (or horror) of being captive to an Idea. Not the lower-case "ideas" in which all our campaigns currently abound, not even the sweeping futuristic vistas of Obama, but the ability to look at government in a transformative way. Reagan was the classic hedgehog, holding to his "one big thing" as tenaciously as any Marxist. Now, with ideology itself on the sickbed, we have become, by default, foxes, knowing many things -- and maybe nothing, after all -- and even a dyed-in-the-wool liberal can feel the diminution. "How are we to proceed without Theory?" cries the world's oldest living Bolshevik in Tony Kushner's "Angels in America." "And what have you to offer now, children of this Theory? What have you to offer in its place?"

Shares