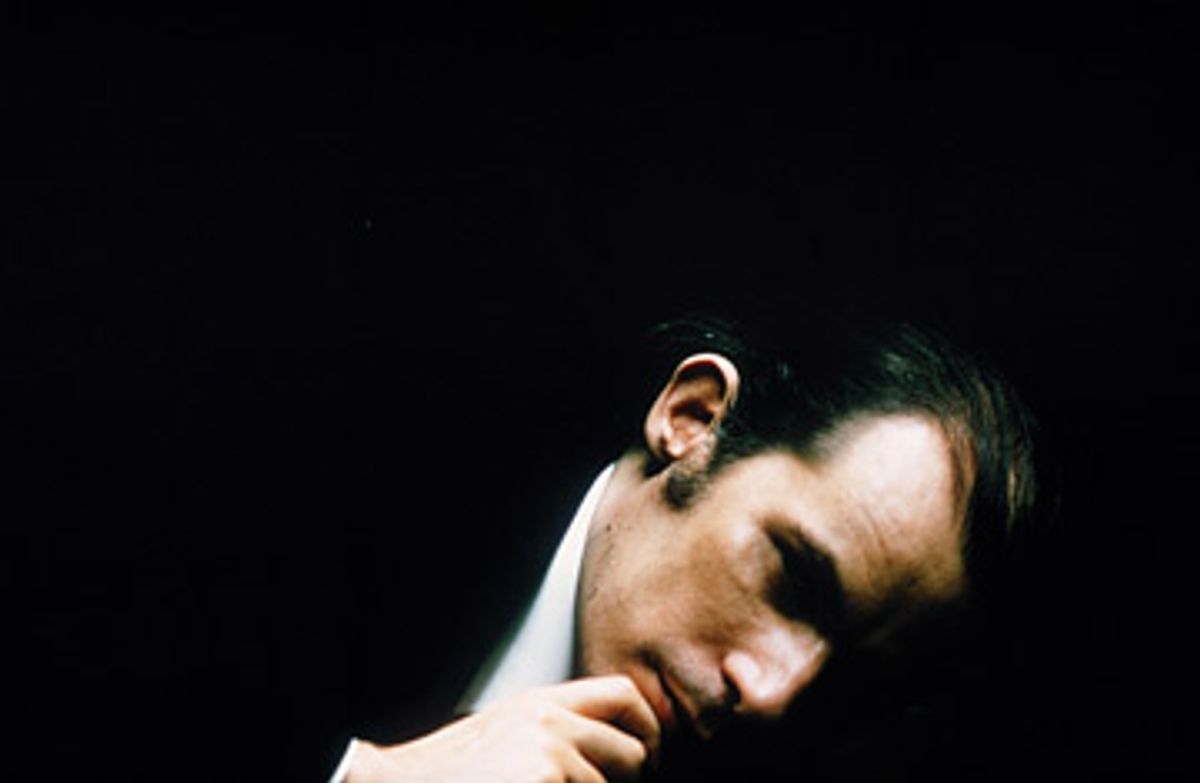

Glenn Gould hummed when he played the piano and it drove recording engineers batty. They tried everything to prevent studio microphones from picking up the pianist's stray voice. A delirious showman, Gould once showed up at a session wearing a gas mask he had bought at a war-surplus store. Listeners too, entranced by his brilliant playing, or charmed by his mad-genius stage presence, have complained that pristine notes of Bach's "Goldberg Variations," Gould's signature performance, and one of the top-selling classical music albums of all time, are lost beneath his rhapsodic vocal hum.

Gould loved to tell interviewers he sang because no piano could match the sound of music he heard in his head. His humming was an unconscious corrective to a piano's physical shortcomings. In truth, Gould picked up the singing habit from his mother when he was first learning to play the piano as a kid in Toronto, and never could shake it.

But that mundane fact doesn't undercut Gould's legendary drive and vision. If he could have, the intellectually electric pianist, who died from a stroke at age 50 in 1982, would have beamed his beloved Bach and Schönberg to listeners without an instrument at all. Performing a piece exactly as he heard it in the concert hall of his imagination was the ideal that forever inspired him. He knew it was impossible to achieve, but that didn't stop him from trying.

In 1974, Gould explained to Jonathan Cott of Rolling Stone that before he sat down at the piano, he created a complete "tactile experience" of a piece in his mind, "so that anything that the piano does isn't permitted to get in the way." For Gould, finding a piano that didn't compromise his inner song was an endless struggle -- a fearful pursuit of perfection that leads to the mysterious heart of his art and personality. Even today, among so many great pianists, it's hard not to ask why Gould sounds so special, outside of time and category, inspiring a reverence bordering on prayer.

Anybody who dares mine Gould's life and legend today is working a site that has been excavated to the bone. In his definitive biography of Gould, "Wondrous Strange," published in 2004, Kevin Bazzana spells out the famous Gould myths and eccentricities exhibited in countless hagiographies.

It's true: Gould played in a ratty low-slung chair that made him appear to be hanging on the keyboard like a drunk. He wore a coat and wool gloves under the hot sun, read a score only once before playing it by heart, lived like a hermit in a lake cottage, ate scrambled eggs nearly every night at 2 a.m. in the same diner, declined to shake hands with strangers and maintained a personal pharmacy rivaled only by Elvis Presley's. But this is not the whole truth. Bazzana impressively separates the myths from the facts of Gould's life, underscoring the pianist's emotional woes, friendships and fantastic sense of humor. He leaves us with the deepest appreciation to date of Gould's mortality and music.

In his careful portrait, Bazzana details Gould's search for the holy piano. But as it turns out, there is more to the story, now nicely told by journalist Katie Hafner, a correspondent for the New York Times, in a new book, "A Romance on Three Legs: Glenn Gould's Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Piano." Hafner draws regularly from Bazzana's biography to frame her story, coloring Gould's piano quest with his famous characteristics. To her credit, Hafner, author of books on Internet pioneers and the Well, the online community, stays focused on a single story line, and offers plenty of fresh reporting to keep her narrative bopping along.

Fueling Gould's quest was his desire to find a piano that felt right for the music he loved. The fastidious Canadian abstained from the boozy romanticism of Liszt and lyrical flights of Rachmaninoff. Dynamic passages in Mozart, he said, "represent an element of theatricality to which my puritan soul strenuously objects." That was one of his diplomatic remarks. "Too many of his works sound like interoffice memos," he wrote of the composer of "The Magic Flute."

Most pianos, notably those made by Steinway, were designed for romantics to bellow a deep bold sound. Yet "Gould argued that projection was far less crucial than clarity," Hafner writes. "He wanted to get a clean, light tone from a piano." That tone, evocative of a harpsichord, suited the spare and exacting works of Bach and Gould's favorite 20th century composers, such as Anton Webern and Ernst Krenek.

Gould also demanded a feather-light touch and hair-trigger action, meaning the piano keys would require only the slightest depression for the hammers to strike the strings. Steinway executives, pioneers in celebrity promotion, did their best to please Gould, although they usually ending up pulling their hair out after receiving his notes, punctuated with mock haughtiness and self-deprecation. About one piano, known by its factory I.D. as 205, whose keys required too much force, Gould wrote, "So unless I change my manner of playing (which would probably be healthier, cheaper and more comfortable) and become a triceps terror, I must conclude that 205 and I have attained the parting of the ways."

Keeping pianos in tune, literally, with Gould required piano technicians with the most refined skills in the business. Hafner distinguishes her book by fleshing out the story of Verne Edquist, "a poor, nearly blind farm boy," who grew up in Saskatchewan and became Gould's chief piano tuner and mechanic. Edquist is a gentle man driven to perfection in his own right. And Hafner's account of him and blind piano tuners throughout their travails in Victorian trade schools and later in living rooms and concert halls is fascinating. Having grown so sensitive to sound, many piano tuners couldn't cope with the noisy world. "In the early 20th Century, piano tuners outnumbered members of any other trade in English insane asylums," Hafner tells us.

Throughout the 1950s, as his fame grew, Gould searched fruitlessly for his dream piano. Then, in 1960, he discovered it under his nose in Eaton's, a department store, in his hometown of Toronto, which featured a concert hall on the top floor. Unfortunately, nobody has attested to being with Gould when he found the piano, known as CD 318, so Hafner is left without a eureka-moment scene. Regardless, she does a delicate job of re-creating Gould's thrill at first touching its keys. As it turned out, he had played CD 318 before, though wasn't sure where, as a concert piano makes the rounds of local halls and arenas. "His ears now remembered its refined sound: the lovely, singing treble and clean, taut bass. And his fingers recalled its extreme responsiveness."

As perfect as the piano sounded to Gould, it was an instrument as mercurial as he, and needed constant attention. Hafner cleverly makes the point that Edquist, as the piano's caretaker, was also looking after its master. "As preternaturally gifted a musician as Gould was, he was still utterly dependent on the technician to keep 318 in top condition," she writes. "So it was Edquist, the man who would tune, regulate, and modify the instrument according to Gould's unorthodox ideas -- some of which horrified the traditionalists at Steinway -- became almost as important to Gould as CD 318 itself." Clearly, Gould was pleased with Edquist, and one day exclaims about his refurbished piano, "It's a chest of whistles, it's a set of virginals. It's just about anything you want to make of it. It's an extraordinary piano."

Hafner ends her central chapter with Gould in high spirits, lending her story a slightly portentous tone, which is intentional. After playing CD 318 exclusively for 11 years, recording numerous albums with it, including his iconoclastic and vivifying takes on Beethoven's famous sonatas, the piano encounters a horrible fate. The unenviable task of reporting it to Gould falls to the brave Edquist. As Hafner recounts the piano's literal downfall, she allows readers to sympathize with the soulful instrument as Gould himself did. It's a deft trick, bridging a connection to the wondrous musician, and stands as the author's best accomplishment.

As a Gould fan, I put down "A Romance on Three Legs" with a grateful smile. I love that it's essentially a book about a piano, a piano tuner and his insane client. Edquist's relationship with Gould reveals a dependent side of the storied pianist that we have never seen before, and that's a wonderful insight. I felt disappointed, in fact, that Edquist faded into the background in the book's second half.

Hafner leaves us with a fine portrait of Gould, but it ends up feeling a little flat. Perhaps any book about Gould sets up expectations that can't be delivered anymore. The Bazzana biography, Gould's own essays and radio shows, interviews with him holding forth in his apartment, stuffed with scores and books, dealing out hilariously pompous and piercing aperçus on Beethoven or the Beatles (hated 'em), and film documentaries that show him driving his big black Lincoln and delivering his benighted outlook -- "My private motto has always been: Behind every silver lining there's a cloud" -- add up to an incredibly vivid picture of the man and musician. It's nearly impossible for a journalist, even a good one like Hafner, to compete with that legacy.

In the end, too, Hafner doesn't quite capture the electricity of Gould's music. Ultimately his quest for perfection isn't about a piano, it's about producing music that's aligned with the stars. Heavyweight classical music critic Richard Taruskin, author of the "Oxford History of Western Music," once wrote that he has no idea how Gould produced certain rolling chords in a recording of a Bach gamba sonata, only that he has been haunted by the chords for years, by the pianist's "famously ahistorical ... uncanny, extraordinary, disembodied touch!"

Disembodied touch is one of the best descriptions of Gould's magical playing. He causes the scales to fall from your eyes about classical music and hear it like you never have before. For me it's his rendition of Bach's Concerto No. 1 in D minor. Although he recorded it before he discovered CD 318, you feel his featherweight hands on the piano, shaping the work with a fearful precision that makes the notes dance in your heart. Gould was 24 when he recorded the concerto with Leonard Bernstein and the Columbia Symphony Orchestra, and you wonder how so much beauty and wisdom could be sealed in his playing. Hafner knows the immortal thing about Gould, even if she doesn't make us feel it as deeply as we could. But then perhaps no writer can: The freak was a genius.

Shares