We can't say we weren't warned.

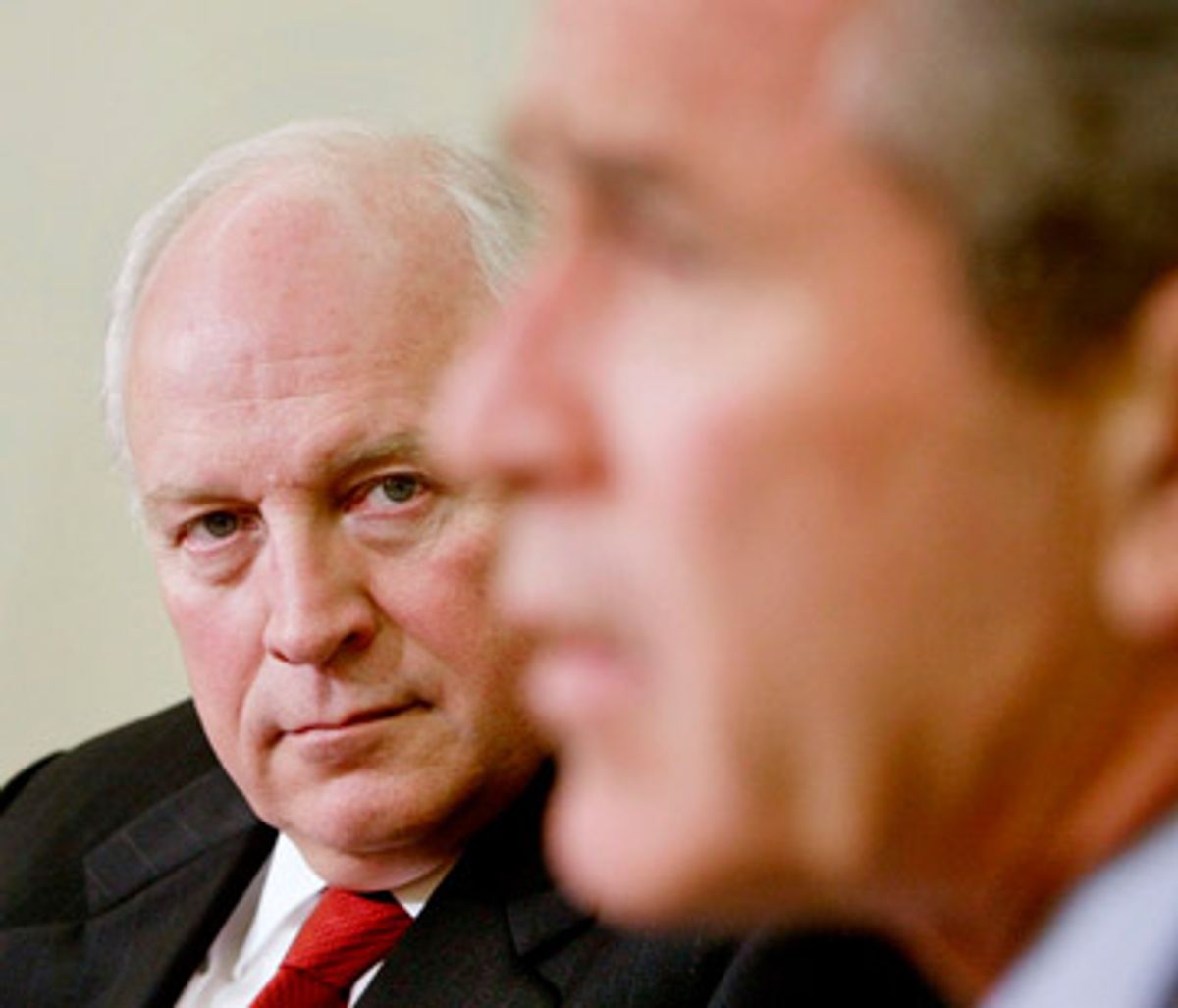

The very first Sunday after the 9/11 attacks, Vice President Dick Cheney descended like a cloud on "Meet the Press" to outline the Bush administration's response. "We'll have to work sort of the dark side, if you will. We've got to spend time in the shadows in the intelligence world. A lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion, using sources and methods that are available to our intelligence agencies -- if we are going to be successful. That's the world these folks operate in. And, uh, so it's going to be vital for us to use any means at our disposal basically, to achieve our objectives."

Around the nation, one presumes, numbed heads were nodding in approval. Whatever it takes to get those bastards. The true nature of our Faustian bargain would not become clear until later, and maybe it needed a journalist as steely and tenacious as Jane Mayer to give us the full picture. "The Dark Side" is about how the war on terror became "a war on American ideals," and Mayer gives this story all the weight and sorrow it deserves. Many books get tagged with the word "essential"; hers actually is.

Above all, it underscores one of the least remarked aspects of our nation's counterterrorist policy: the degree to which it has been driven not by spies or generals but by pasty men in ties. "The first thing we do," goes that crowd-pleasing line from Shakespeare's "Henry VI," "let's kill all the lawyers." Readers of "The Dark Side" might be moved to add: "Before they kill you." Almost from the moment America was attacked, Mayer writes, Cheney "saw to it that some of the sharpest and best-trained lawyers in the country, working in secret in the White House and the United States Department of Justice, came up with legal justifications for a vast expansion of the government's power in waging war on terror. As part of that process, for the first time in history, the United States sanctioned government officials to physically and psychologically torment U.S.-held captives, making torture the official law of the land in all but name." This "extralegal counterterrorism program," contends Mayer, "presented the most dramatic, sustained, and radical challenge to the rule of law in American history."

We already know, of course, that wars give presidents plenty of room for overreaching. Lincoln suspended habeas corpus during the Civil War; FDR, during World War II, interned hundreds of thousands of Japanese-Americans. What separates the Bush White House from its forebears, suggests Mayer, was that its "doctrine of presidential prerogative" admitted no challenge and operated, as much as it could, out of sight.

And yet so much of it happened on our watch. Nov. 13, 2001: The White House proclaimed a state of "extraordinary emergency" and announced plans to try "enemy combatants" before military commissions. Jan. 8, 2002: President Bush nullified the Geneva Conventions. Aug. 1, 2002: The Justice Department issued the now-infamous "torture memo." Written largely by White House lawyer John Yoo (later to join the University of California at Berkeley faculty), the memo deliberately removed whole realms of pain from the category of "torture." What was left? Mental suffering "of significant duration, e.g., lasting for months or years" and physical suffering that causes "organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death." Everything else was in play.

These were not semantic distinctions because, by then, the U.S. military had the perfect laboratory for putting Yoo's memo into practice: a prison camp at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, that promised interrogators "total isolation, total secrecy, and total control." But who exactly was being interrogated? Mayer's big find is a classified CIA report from the summer of 2002, in which a senior analyst concludes that one-third of the camp's 600 prisoners have no connection to terrorism whatsoever. That figure was later amended by an FBI counterterrorism expert, who argued that no more than 50 of the detainees were worth holding. These findings directly contradicted administration assertions that Guantánamo harbored only "the worst of the worst." Not surprisingly, the administration refused to review the detainees' cases, with the result that many of them are still there, years after their initial incarceration -- and still without legal recourse because they have never been charged with a crime.

Behind the Guantánamo debacle lies a serious question: Do suspected terrorists deserve the same rights as you and I? The answer for Cheney and his lawyers was an unequivocal no. And with that no, a whole world of yes blossomed forth. Bush administration officials could now shut away terror suspects in clandestine prisons called "black sites." They could ramp up the little-used practice of "extraordinary rendition," allowing the CIA to kidnap dozens of suspects and extradite them to countries -- notably Egypt -- where torture could be practiced with greater impunity. President Bush, not quite grasping the appearance problem, hoped to publish a running tally of these kidnappings, so Americans could keep score from home. CIA director George Tenet talked him out of it.

The Bush administration could also co-opt a secret program called Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape (SERE). Originally designed to train U.S. military personnel in resisting enemy torture, the program, as opportunists soon found, could also be used to torture enemies. SERE techniques were initially approved only for al-Qaida logistics chief Abu Zubayda, but within months, they had migrated to Guantánamo, where the U.S. military, Mayer writes, began "subjecting prisoners to treatment that would have been unimaginable, and prosecutable, before September 11" -- hooding, sleep deprivation, stress positions, extremes of temperature, and a rich array of often sexual humiliations. (Suspected 9/11 accomplice Mohammed al-Qahtani was stripped naked, ordered to bark like a dog and forced to wear variously a leash, a bra and thong underwear.) The SERE template was then exported to the detention facilities of Iraq, and it wasn't until the dissemination of the Abu Ghraib photographs that Americans could see what had been wrought in their name.

Sadism, as Orwell taught us, is best screened by syntax, and administration lawyers were especially adept at the neutering of language. Interrogations were merely "special" or "enhanced" or "robust" and were always consistent with the Bush administration's "new paradigm." Under duress, these euphemisms morphed into denials. "We don't torture," announced Vice President Cheney. "Torture is never acceptable," Bush told the New York Times in January 2005. "Nor do we hand over people to countries that do torture." But even the administration was hard-pressed to put a happy face on waterboarding -- though the media certainly did their part to help, describing the practice in such value-neutral terms as "simulated drowning." "It's not simulated anything," explains one SERE instructor. "It's slow-motion suffocation with enough time to contemplate the inevitability of blackout and expiration ... You can feel every drop. Every drop."

Much of Mayer's reportage has previously been published in the New Yorker, but the effect of stitching it into a unitary narrative gives it an epic trajectory, as well as a cast of characters that the late Joseph Heller might have conjured up. Meet suave Donald Rumsfeld, who, when pressed on the issue of Guantánamo, snarls, "I don't do detainees," and who, upon hearing that prisoners are forced to stand four hours a day, counters that he often stands for eight to 10. Meet empty suit Alberto Gonzalez, the former attorney general, who sits in virtual silence through meeting after meeting. Is he, a White House lawyer wonders, "one of those people who don't talk, because they're so smart they know it all, or one of those people who keep their mouths shut because they haven't got a clue"? I'll let you guess which it is.

But the bureaucratic colossus who bestrides this narrow world is David Addington, Cheney's general counsel and a figure of Robespierrian purity. "Tall and bespectacled," with "the look of an irascible sea captain," Addington jealously guards the paper flow to Cheney and, ultimately, to Bush -- even as he shouts down all opposition. No one stands to his right, and no one challenges him without risk of career suicide. "We're going to push and push and push," he tells one colleague, "until some larger force makes us stop."

"The Dark Side" shows us what happens when men lose themselves and also, in a scary way, find themselves -- becoming the pencil-necked alphas they have always dreamed of being ("When we're through with [al-Qaida]," promised Cofer Black, the CIA's senior counterterrorism official, "they will have flies walking across their eyeballs") and realizing long-cherished dreams. Cheney and Addington, for their part, got what they had been waiting for half their lives -- the chance to shift power back to the executive branch. By arguing that the president needed free rein to fight al-Qaida, they were able to expand domestic wiretapping, neutralize Congress, and undo many of the restraints that Watergate had put in place three decades earlier. Their ultimate goal, as Rep. Jane Harman put it, was "restoring the Nixon presidency."

This was, in short, a quiet coup, and we can be grateful at least that it was opposed not just by public-interest and human-rights groups but by individuals within the Bush administration. FBI special agent Jim Clemente, Navy general counsel Alberto Mora, Deputy Attorney General James Comey, Justice Department attorneys Jack Goldsmith and Dan Levin all had shining moments of resistance (though Mayer scrubs their pedestals a bit too hard). They weren't, however, very effectual. Most either fled or were banished soon after raising their voices. Even John McCain, who quite commendably authored a bill prohibiting U.S. personnel from torturing prisoners, saw his work undone by presidential signing statements (crafted, naturally, by Addington).

Today, not a single terror suspect held outside the U.S. criminal court system has received a trial, and despite Supreme Court slapdowns, the fretwork of loopholes carved out by Cheney's Boys is largely intact. For seven years, then, the Bush administration has operated with untied hands. And for all that, Osama bin Laden remains at liberty; so does Ayman al-Zawahiri; and the al-Qaida threat, according to the most recent National Intelligence Estimate, is once again mounting.

And so we must ask ourselves at last if terror is the best answer to terror. Mayer has her doubts. "Torture works in several ways," she summarizes. "It can intimidate enemies, it can elicit false confessions, and it can produce true confessions. Setting aside the moral issues, the problem is recognizing what's true." Mohammed "confessed" to planning the assassinations of Presidents Clinton and Carter, as well as Pope John Paul II. Zubayda, under assault, spun outlandish tales of "plots to blow up American banks, supermarkets, malls, the Statue of Liberty, the Golden Gate Bridge, the Brooklyn Bridge, and nuclear power plants," sending law-enforcement officials scurrying down any number of blind alleys.

The greatest damage came from Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi. Chief of an al-Qaida training camp, he was captured by Pakistanis shortly after 9/11 and handed over to Egyptian interrogators, who pressed him for damaging information on Saddam Hussein. Al-Libi didn't even understand what "biological weapons" were, and at first he was so confused by the line of questioning he couldn't come up with a story. Soon enough, he figured out what his interrogators wanted, and the tale he fabricated -- WMD flowing in an unbroken line from Saddam to al-Qaida -- became a decisive factor in the decision to go to war. When asked later why he had lied, al-Libi had a simple explanation: "They were killing me. I had to tell them something."

One needn't sympathize with al-Libi, who was complicit in the killing of thousands, to recognize that torture, as a tool of war, can be profoundly counterstrategic. A former MI5 security officer believes the United States is falling into the same trap as 1970s Great Britain: "They violated people's civil liberties, and it did nothing but radicalize the entire population." To see how that plays out over time, look no further than al-Qaida itself, which, as Lawrence Wright's "The Looming Tower" argues, was born not in Soviet-occupied Afghanistan but in Nasser's prisons. There, thanks to a steady diet of torture, Islamic extremists metastasized into Islamic terrorists. After reading "The Dark Side," one can only ask: What rough beast is slouching from Guantánamo, waiting to be born?

Shares