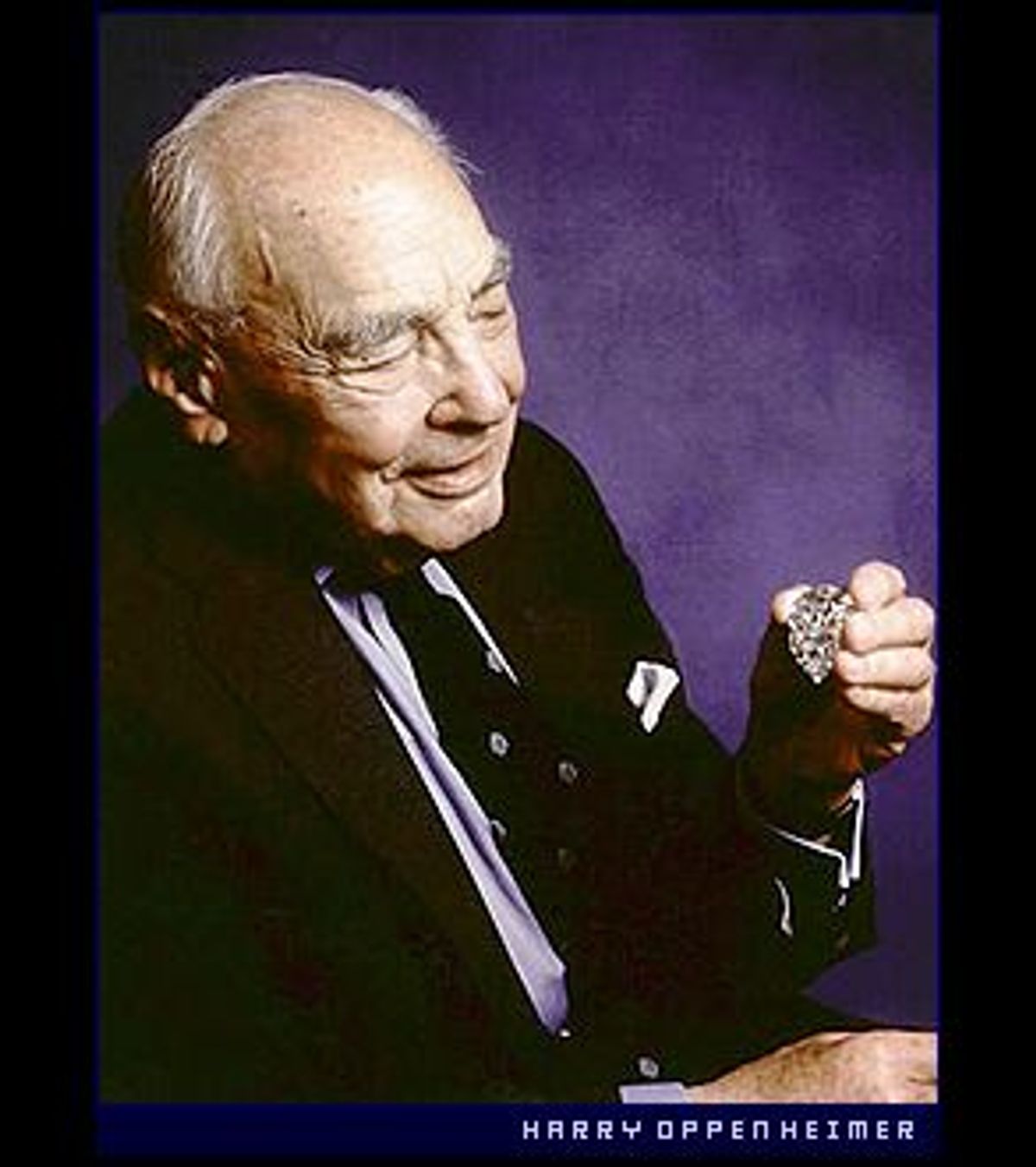

Nothing lasts forever and with the death this August at 91 of Harry Oppenheimer, the South African diamond magnate and former CEO of the De Beers cartel, the end of an era in which the world's diamond supply is exclusively controlled by one company and one family may be at hand.

In his 27 years as CEO of De Beers, from 1957 to 1984, Oppenheimer became one of the world's wealthiest men. During his tenure, De Beers controlled between 80 and 90 percent of the world's diamond supply. His many companies, most notably Anglo-American Trust and De Beers Consolidated Mines, at one point constituted 54 percent of the South African stock market's total assets. He was even one of the first white people who Nelson Mandela wanted to see upon his release from Robben Island Prison -- although this was perhaps more a sign of Oppenheimer's willingness to recognize the significance of the African National Congress for the smooth running of his business than testament to his great moral virtue.

Oppenheimer inherited control of De Beers from his father, Sir Ernest, who seized the reins of the diamond empire of Cecil Rhodes -- eponymous founder of Rhodesia and the prestigious Rhodes Scholarships -- in 1929, mere months before the U.S. stock market crash. Although it was Sir Ernest who built De Beers into a worldwide cartel, it was Harry Oppenheimer who strengthened his father's legacy through his ingenious sculpting of the public's demand for the rock. Since inheriting the chairmanship two years ago, Harry's son, Nicky, has been charged with maintaining the cartel's market domination while appearing to offer the transparency a modern business demands.

But Nicky has a rough road ahead. The growing outcry against the marketing of so-called conflict diamonds or blood diamonds -- defined by one human rights organization as "diamonds that originate from areas under control of forces that are in opposition to elected and internationally recognized governments" -- expanding antitrust legislation in both the United States and Europe, and the rise of new diamond suppliers outside De Beers' realm of control are combining to undermine the company's hitherto unchallenged domination of the world diamond market. But never fear -- following his father's example, Nicky Oppenheimer hopes to market De Beers out of its current troubles.

Despite its elite status, the diamond, which can be found in abundance from southern Africa to Australia to northern Canada, is not the rarest of gems. With no intrinsic value, all a gem-quality diamond has to offer is the perception of its preciousness. As a symbol of eternal love, the tradition of the diamond engagement ring has become so pervasive that it's hard to believe that this is a fairly recent phenomenon. And an extremely calculated one -- the result of a marketing campaign developed at a time when the demand for diamonds had sunk to an all-time low and an increasing supply threatened the precious (as opposed to semiprecious) nature of the stones.

In 1938, nine years after seizing control of De Beers, in the wake of the Depression and with Europe bracing for another world war, Sir Ernest Oppenheimer found himself with no place to market his wares. Rather than risk a plunge in the status and price of diamonds, he sent 29-year-old Harry from Johannesburg, South Africa, to New York to meet with the N.W. Ayer advertising agency. The plan was to transform America's taste for small, low-quality stones into a true luxury market that would absorb the excess production of higher-quality gems no longer selling in Europe.

As Edward Jay Epstein outlined in his 1982 book "The Rise and Fall of Diamonds," N.W. Ayer saw the challenge as one rooted in mass psychology, meticulously researching the attitudes of American men and women about romance and gift giving. From this research, the slogan "A Diamond Is Forever" was born, launching one of the most brilliant, sophisticated and enduring marketing campaigns of all time. Without ever mentioning the name De Beers, the campaign set out to seduce every man, woman and child in America with the notion that no romance is complete without a rock -- and the bigger the rock, the better the romance. That men also now had a way to show the world how much money they made was an added bonus.

With the help of gossip sheets packed with stories of diamond rings and romance, De Beers transformed the United States into the premier market for the world's gem-quality diamonds. Once it conquered the hearts and wallets of America, it set out to conquer Japan and Brazil, and when World War II was over, it began the reconquest of Europe.

The slogan "A Diamond Is Forever" was also designed to convince the purchaser that although a diamond is a good investment, for sentimental reasons no rock should ever be resold. Given the continuous mining of new stones -- not to mention the half-billion or so carats that will never rust, break or wear out walking around on the hands, necks, ears and lapels of hundreds of millions of women -- the last thing De Beers wants is to have previously sold stones coming back onto the market.

De Beers has enough problems dealing with the oversupply of new diamonds. In the mid-1950s De Beers was overwhelmed by a flood of small diamonds pouring out of recently discovered mines in the Soviet Union. After nearly a decade and a half of convincing America of the importance of larger stones, suddenly the company needed to create a virtue out of the previously disparaged small diamonds. To accomplish this, De Beers invented the "eternity ring," a single, unbroken band of up to 25 evenly matched small stones. The ring was introduced in the early '60s as the best way to renew vows in the home stretch of a long marriage and the best way to wear diamonds without the ostentation of big stones. Today, the United States absorbs 50 percent of the world's diamonds, with an estimated 70 percent of American women owning at least one rock.

As it turns out, this ideal of perpetual ownership is a healthy delusion for the owners of all but the rarest and most expensive diamonds. Despite the illusion that it retains its value, a diamond can only be sold for less than its wholesale price, not what one would consider a good return on investment.

Nonetheless, the rock is alive and well as a status symbol in America, and the current cachet of colored diamonds has added an extra degree of elitism to the raging luxury marketplace. Despite what the industry refers to as "competing luxuries" (four-figure handbags, five-figure watches and six-figure cars), this fall's marketing blitz for the rarer-than-rare black diamond will ratchet up the stakes even further.

But manipulating perception isn't the only way De Beers has maintained its control. As has been extensively reported in a number of publications, including the Economist, the Atlantic Monthly and Stefan Kanfer's 1993 book "The Last Empire," De Beers has also manipulated an artificial sense of the diamond's scarcity by buying up new mines, freezing out challengers and mopping up excess supply. Through a web of intricately intertwined businesses, De Beers successfully created a cartel in the strictest sense of the word, staving off dreaded price fluctuations by controlling everything from the stones' removal from the ground to their delivery into the hands of jewelers.

The Central Selling Organization in Europe handles the purchasing and sorting of stones from its far-flung field offices, then sorts and values the stones in preparation for sale. The Diamond Trading Company in London channels first-tier sales through an arcane ritual of "sights," where 125 handpicked buyers, or "sightholders," meet in London 10 times a year for the privilege of purchasing a nonnegotiable, preselected box of assorted unpolished stones on an all-or-nothing basis. The Syndicate in Israel, as well as cutters and polishers in India, Belgium and New York, process the stones for the next tier of buyers.

But now there are new pressures on the horizon for De Beers that are forcing it to back away from abundant supplies of some of the world's finest raw diamonds in order to preserve its image on the battlefield of public perception. Using the phrase "conflict diamonds" or "blood diamonds," Global Witness and the United Nations, among others, are drawing attention to the cost of human suffering associated with diamonds, forcing a level of accountability into an industry that has been notoriously low on disclosure.

By focusing on the carnage associated with conflict diamonds these groups have forced De Beers to distinguish between diamonds mined in peaceful countries controlled by legitimate governments and diamonds harvested at gunpoint by rebel forces in places like the Congo, Sierra Leone and Angola, where endless battles have turned some of the world's most minerally rich countries into what the United Nations Children's Fund has called the worst places on Earth to be a child. The money generated from the sale of conflict diamonds goes to buy more guns, which perpetuate the battles over control of the diamond mines. Until this recent pressure, De Beers admitted in its public statements and annual reports that it was the purchaser of a large portion of Angolan stones.

In an ironic twist on De Beers' longstanding ability to control perceptions, the company is now attempting to transform its discomfort into a marketing virtue, seizing this moment to develop a consumer brand identity out of its previous anonymity. De Beers announced earlier this year that it intends to embargo all conflict diamonds and provide a certificate of each stone's origin with each sale. To ensure compliance, the company announced its intention to hold its sightholders to the same standard. In doing this, De Beers is hoping to establish itself in the public's mind as the dividing line between the forces of good and the forces of evil, a self-appointed clearinghouse that will prevent buyers from bloodying their hands in the simple pursuit of luxury. From now on, you'll know if that big rock your fianci just put on your finger was dug out of the ground by brutalized children or waddled out of a war zone in a smuggler's rectum.

Human rights groups have praised De Beers' promise to embargo the conflict diamonds as the only ray of hope on a very bleak landscape, but the embargo still fails to address the simple truth that one of the diamond's historic virtues and liabilities is that it packs a lot of value into a very small package. This is highly transportable wealth. Millions of dollars can be walked across a border to a nonconflict zone in a sock and multimillions can be carried in a small suitcase. Because of the extremely high quality and large size of the diamonds being mined in Angola and Sierra Leone, allowing such a profitable and abundant supply onto the open market would undermine De Beers' control of its cartel.

Unfortunately for the world's policing agencies, the good stones and the bad have been mixed together for so long that it is virtually impossible for all but highly skilled gemologists to tell them apart. Global Witness holds that it is not as difficult as generally believed to distinguish the origin of the raw stones, but even it concedes that once the diamonds are polished, the traces of their geographic origins are erased. Conflict diamonds account for 15 percent of the world's supply, an estimated 50 percent of which ends up in the United States.

De Beers' use of the branding process to guarantee access to guilt-free diamonds comes at a time when the European Union and the U.K. are trying to implement antitrust regulations modeled on those in the U.S. -- where De Beers has already been repeatedly investigated and indicted for its trade in industrial diamonds. In part due to the Department of Justice's inability to win a conviction against De Beers because of the inaccessibility of evidence, Congress passed the 1994 International Antitrust Enforcement Assistance Act -- aimed at opening doors for the sharing of information on antitrust cases with foreign governments. Citing De Beers' anti-competitive practices, the Department of Justice continues to block the company from directly conducting business in the U.S.

De Beers appears to have realized that the writing is on the wall for its cartel, in any case. This July, with the help of American management agency Bain & Company, De Beers announced a radical new business plan that attempts to deal with all of De Beers' problems at once. In addition to the certificates of origin, De Beers announced that the company intends to end the system of stockpiling diamond supplies to control prices. By reducing the assets it has tied up in the stockpile from $3.9 billion to $2.5 billion, it hopes to increase profitability and free up extra cash to spend on the advertising of diamonds as a branded luxury item.

De Beers will use the innocuous sounding Diamond Trading Company as its brand name, identified by its "forevermark" logo. Evidenced by its recent request to meet in Europe with Assistant Attorney General Joel I. Klein of the antitrust division, De Beers may realize the desirability of resolving the antitrust impediments to becoming the Coca-Cola of diamonds, despite the cost. Klein has so far turned down the invitation.

De Beers' competitors have been emboldened by this weakness in De Beers' fagade. In 1999 Tiffany & Co., a sightholder and one of the world's largest buyers of diamonds, made a side deal with Canadian miners for an independent supply of diamonds, betting that the Tiffany & Co. brand name, with its signature pale blue boxes and white ribbons, would be just as sparkling as a De Beers logo. To make matters worse, Australia, which has discovered enormous diamond reserves in its Argyle mines, has begun to sell its stones directly on the world market, bypassing De Beers entirely. Certain Russian mines have also allowed their distribution contracts with De Beers to lapse in an attempt to take their goods straight to market.

In the meantime, De Beers is carrying on the Harry Oppenheimer tradition of mentoring the diamond buyer through major life decisions. Using its Web site, it answers all the objective questions about cut, clarity, color and carats, while paternalistically educating the consumer about the symbolic meaning of diamonds, an appropriate salary-to-expenditure ratio and how to glean the maximum psychological impact from the presentation of the gift. It offers 12 original "Ways to Surprise Her," ranging from having "a cake on display in the window of her favorite bakery with your personal message and topped with the diamond" to the unimaginably ironic: making "the diamond a game piece during a game of Monopoly."

Try it. It worked for Harry Oppenheimer.

Shares