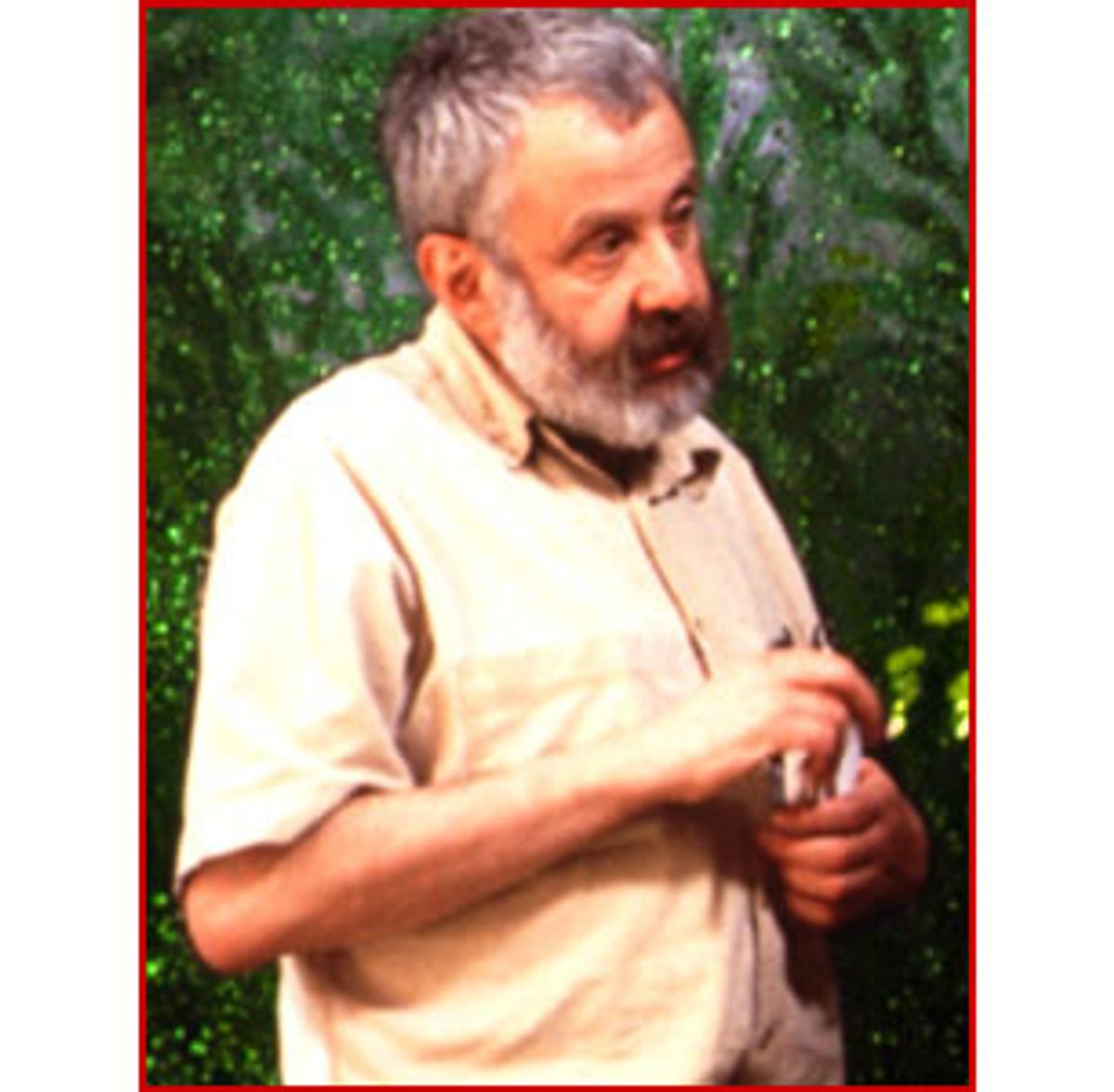

Starting with his big-screen breakthrough 11 years ago with "High Hopes" and continuing with films like "Life Is Sweet" (1990) and "Secrets and Lies" (1995), British moviemaker Mike Leigh has gained a unique international reputation. Again and again, he's taken actors so far into unpredictable realms of heightened realism, usually in gritty urban settings, that their performances become as mysteriously and tragicomically complete as Dickensian portraiture.

Leigh has done this by developing a technique of creating characters through in-depth research with carefully selected casts. For three decades, his work for British stage and television carried the credit "devised and directed by Mike Leigh," because his dramatic situations and his story lines were so indebted to the intense talk and organic interplay between him and his ensembles.

Now, in "Topsy-Turvy," he has gone back to the London of the Dickens era (the movie begins in 1884, 14 years after Dickens' death). Leigh has taken his cutting-edge methodology with him and emerged with his most seductive and outlandishly successful picture yet. A few days after we spoke over lunch in San Francisco, Leigh's film won 1999 best picture honors from the New York Film Critics Circle -- and the group named Leigh best director.

On the "Topsy-Turvy" CD (just released on Sony Classical), Leigh writes in a short essay:

The popular musical theater of the English-speaking world of a hundred years ago was dominated by Gilbert & Sullivan, two Londoners of contrasting temperament, whose battles gave us fourteen delicious, bittersweet comic operas. The impresario who presented these shows and built the Savoy Theatre for them was Richard D'Oyly Carte, and for thousands of British children in the 1950s our annual treat was the visit of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. We queued for tickets, we clapped the encores, we bought the long-playing records, we memorised Gilbert's hilarious words, and of course we embarked on the journey through our teens and into our adult lives humming and whistling Sullivan's infectious tunes.

"Topsy-Turvy" is Leigh's grand display of gratitude. It takes up Gilbert and Sullivan's career at a volatile time. Sullivan (Allan Corduner) is impatient with Gilbert's penchant for suggesting scenarios "rich in human emotion and probability" only to turn them topsy-turvy with magic pills and potions. And Gilbert (Jim Broadbent) views Sullivan's reluctance to continue on this path as an insult. It's Mrs. Gilbert (Lesley Manville) who comes to the rescue when she drags her husband to an indoor re-creation of a Japanese village, including imported Japanese people. The pleasurable jolt of this exotica stimulates Gilbert to cook up "The Mikado" -- and though it's hardly richer "in human emotion and probability" than, say, "Princess Ida," it amuses Sullivan immensely and ends up salvaging the partnership.

Leigh's liner notes say he aimed to fashion "a film about all of us who strain and struggle to make other people laugh" that would also be "a celebration of Gilbert's wit and a feast of Sullivan's music." But with rounded depictions of performers as different as the droll, neurotic George Grossmith (Martin Savage) and the tremendously humorous Richard Temple (Timothy Spall), he also achieves a portrait of the actor's craft as inspiring and poetic as Jean Renoir's "The Golden Coach." And Leigh does it his own way -- from the ground, and greasepaint, up.

Leigh's theater world mirrors the real world's density and conflict. When Gilbert cuts Temple's solo from "The Mikado," the chorus protests in a dazzling display of what Leigh terms "grass-roots politics." Gilbert and Sullivan's conventions echo and challenge Victorian mores: Gilbert must reassure leading man Durward Lely (Kevin McKidd) that he isn't being lewd when his wandering-minstrel outfit shows his calf. At times, Leigh points up the fragile insularity of theater. His camera eavesdrops on Grossmith as the actor and two colleagues smugly expatiate on the Empire-shaking catastrophe of the massacre of General "Chinese" Gordon and the defenders of Khartoum. (Grossmith sniffs that Gordon shouldn't have expected natives to play by the rules.) Later, Gilbert runs into a madwoman from London's lower depths while pacing through the streets on his "Mikado" opening night.

During lunch with me last week, Leigh confessed: "I love those sorts of juxtapositions. Part of it is, I don't have the passion for theater that I have for film; one of the things I hate is that theater has a claustrophobic nature, whereas filmmaking lets you out into the world. So at certain points, I felt the need to let the air in. It's just wonderful, halfway through, to suddenly proclaim, in a caption, that news reaches London of Gordon's death. It makes you feel like you're opening a music box."

Yet even more unexpected than these signature moments are this film's lyrical flights, which reveal how much Leigh does instinctively adore the theater. "I had to have a narrative, dramatic or faux-dramatic reason for each musical number," Leigh said. But he ends the film, stunningly, with a number that here makes only poetic

sense. D'Oyly Carte actress Leonora Braham (Shirley Henderson), a melancholy

widowed mother, once more takes on the role of Yum-Yum from "The Mikado" and

sings the gorgeous "The Sun Whose Rays Are All Ablaze."

"We're very wide awake/The moon and I!" Yum Yum announces in the heart-stopping last lines. In "Topsy-Turvy" no one is more magically moonstruck than Mike Leigh.

Of course "Topsy-Turvy" will be treated as a radical departure for you, and in some ways it is. But I settled into it happily as a Mike Leigh film.

I think that's dead right. The suggestion that it's in a different genre from my other films is preposterous. It's exactly in the mode of its predecessors. Not only do I deal with character and stuff in the same way, but with the exception of the use of flash-forwards, it's shot consistently in the same sort of style and it has the same approach to film narrative. The surface differences are that it's period, and it's not, in the usual way, about ordinary people. But people are people.

And when you see how this enormous group enterprise operates, you do get a sense -- which you usually don't get with theater films -- of actual work getting done.

Well, I hope so, yeah. This film is about an industrial process. When you reach the stage where you understand the politics and economics of the theater and Sullivan's creative crisis, and it's really about time you saw the work, you get this healthy chunk of "The Sorcerer," which is obviously useful here because it has a topsy-turvy magic-lozenge plot. And the way I filmed that sequence, you are looking at the industrial process -- you see the conductor directing the band and the chorus in the wings, and you see the guys with the props and sound effects and the guys with electric wires.

It makes Gilbert and Sullivan immediately accessible. When I was a kid watching their operettas on Sunday-afternoon TV shows, done in a period style, the performances always seemed distant and fake to me. What struck me as a touchstone in your movie is that when you see your players in makeup, close-up, with their obvious head pieces and so on, you completely forget about the artificiality, or you see it and you go with it.

I think that's true. Although to be fair to the people that inevitably are being criticized in what you say: If you actually made a film, say, of "The Mikado," and you saw all the wigs and stuff like that, you would simply find it illogical. You wouldn't believe in it, if you can believe in that theatrical sort of story anyhow. But if you know that what you're looking at is real people who are doing something which happens to be play-acting but that in itself is totally real, then you believe. It's not fair to compare what we do with those productions, crap though they no doubt were.

Of course, I wasn't making a critical judgment at age 8 or 9.

But I am. And that's because one of the subsidiary agendas with the film was to say: "OK, let us strip away the rusty encrustations and the barnacles -- all the layers and layers of coyness and whimsy which isn't what Gilbert and Sullivan is about. Let us access the actual stuff that's been hidden from us by generations of various growths over the course of over a century, like bad performances and shows which are inherently youthful being played by overweight, middle-aged people." Going back and looking at Gilbert and Sullivan pure -- as the modern, fresh, vibrant kind of culture that, for all its eccentricities, their theater was -- helps it to come alive.

The film is being treated as a quintessential period piece, but to me it redefines what a period piece does.

Without being too self-congratulatory about it: I'm sick of period films, not a few of which come from the United Kingdom. You look at them and they're not real. You say, "Yeah, OK, but where are the people?" I mean, I quite like "Shakespeare in Love," but it is plainly on a totally different trip from "Topsy-Turvy" because it's very healthily and anarchically a spoof and "Topsy-Turvy" is not -- it is absolutely serious. I wanted to subvert the costume drama. I could have done a movie about poverty in the East End of London in the 1880s if I just wanted to do a period piece. But to subvert what appears to be a "chocolate-box" subject by making it real seemed to me to offer a lot more scope.

You emphasize Gilbert's modernity as a theater pro. You include a hilarious bit with him getting the box-office take over the telephone, in code. How did you incorporate these historical details and still remain true to your technique of building characters through immersion in the material with the actors?

Oh, to be honest, I have nothing to report that's particularly remarkable except that we did the homework. We researched all the books on Gilbert and Sullivan and the music that there are, and all the archive material available on either side of the Atlantic. We studied everything you can think of -- society, politics, etiquette, you name it. And at the same time we did the hands-on, practical, physical-workshop stuff that we do, until the two kinds of preparation became one.

As far as language goes, just reading the dialogue in "Punch" cartoons of the period gives you access to how people talked of what was going on. And there were quite a few seasoned Dickensians amongst us. And a portion of what is said in the film is direct quotation. In the scene where Gilbert goes to see Sullivan in his apartment, where they sit on the sofa and eat lump sugar, and in the later scene in D'Oyly Carte's office, where the shit hits the fan and they reach their impasse, we use things that they actually said. Woven, I hope seamlessly, into both of those scenes are quotes from letters and correspondence. And then there are the Gilbertian epigrams that Gilbert says in the film, or things that sound epigrammatic --

Like "I'd rather spend an afternoon in a Turkish bath with my mother than visit the dratted dentist -- "

Some of them he actually said, some of them Jim Broadbent improvised, and some I contributed. Basically, you get the hang of it. And that's what we do with these films. You get the hang of a character and then you can sort of extend it and expand it.

Not just with language, but with body language.

Yes! That's partly to do with studying etiquette, but also, as always, with everybody rehearsing months in costume -- which I have to say if there was one major hassle in the film it was waiting for all those women to get into those bloody corsets, which takes forever. You realize why people had servants.

So many conventional period films seem to get the physicality wrong.

They don't wear corsets! They don't wear corsets! So they don't have the right silhouette. The question is, "How do you make something 'contemporary' -- i.e., for us?" My own feeling is that you don't succeed in doing that by compromising, because then it's neither one thing or the other. What we've tried to do is to say, "OK, let's really go for it." And then the texture comes alive and becomes as contemporary as anything. After all, if you could take a movie camera and get into a time machine and go back there and film the reality, it would be much more alive than anything that you would achieve by half-reconstructing it. I always think that film in some way should aspire to the condition of documentary. Which isn't to say you should try and make something like a documentary but merely that when you make a documentary, you never question that what you're filming exists in three dimensions or that whether you film it or not, it exists. Often I have all sorts of stuff which we don't film, but it's there. It helps give a kind of integrity to the bit you do film.

If you were able to travel back to D'Oyly Carte's theater in 1884 with a movie camera, you'd want to include matters that wouldn't be observed or spoken about in theater pieces of that era, including the intense preparations and gossip -- and the alcohol and drug use -- going on backstage.

If you're saying that the philosophy of what we choose to look at is very, very un-Victorian -- oh, absolutely. I don't quite know what sort of film it would be if you tried to tell the story from the parameters of these characters' perception. I mean, that would be, I suppose, a kind of spoof of Victorian drama. No, I am simply looking at them as people, according to the basic principles that we're born, and we die, and we get up in the morning and go to the lavatory, and that is what it's about, isn't it?

From the start, you put the audience in a humorous quandary: We don't know how to figure Gilbert out. There's a wonderful incongruity between the humor he comes up with and --

And his dourness. I know, it's fascinating. To tell you the truth, that's the reason why I went to such lengths (and lengths we went!), both in preparation and in finishing the film, to imply something about his parents and his family. His mother and father were certainly as balmy as we suggest, which gives an implicit indication as to Gilbert's own personality.

He is dour, and paranoid, and dogged. But if you are as smart as Gilbert is, and you are doing things that are new, you may feel you have to doubt easy victories and trust only your own critical faculties. We see the acuity behind his craziness in the rehearsal scenes; to me they are the core of the movie.

You're making me think of something that I hadn't actually thought of until this moment. Of course, we present Gilbert as, in fact, a pioneer of directing; but what hadn't occurred to me, in so many words, until now, is that he has the quality of an archetypal director. That ability to be both involved and detached.

Was Jim Broadbent always the choice for Gilbert?

Yeah. Did you ever see that short we made, "A Sense of History?" We were shooting that in January of 1992, the year we made "Naked." We were on this farm, in sub-zero temperatures, and he was just doing this bit. During the take, I suddenly just went, "Ping!": Gilbert. And when we finished the film a few weeks later, I said to him, "Look, I have this idea which is crazy and you won't believe it, but, I think you should play W.S. Gilbert. And I'm gonna lend you some books." And he plainly thought I'd lost it. So we sat on it for quite a long time, partly on the question of who was going to play Sullivan. And fortunately, thank goodness, I had a really good casting director who pointed me in the direction of Allan Corduner. The truth is, nobody else could have done it, I think.

Sullivan -- despite his kidney trouble and with all his libertine dalliances and travels -- comes off as a blessed sprite.

Yeah. And was, I think.

And Corduner is such an uncanny performer that he can play that and be able to make it palpable, not just metaphoric.

I think it's a remarkable performance, I have to say.

It struck me that part of the cumulative effect of it comes from his authority as a conductor, and his rapport with the musicians.

Yeah, Corduner himself is an amazing musician. You can see it in the way he plays. He just is. And he learned conducting. So it's a real bonus that we kick off with that real conducting of his going on so early there. Corduner's been in lots of movies playing small parts, and, indeed, was on Broadway playing the chief steward in "Titanic," the musical, when I auditioned him for this film. He's a dramatic actor, but occasionally does musicals.

You did round up a lot of your regulars, like Timothy Spall as this abused master actor, Richard Temple.

He is fabulous. You know, he is musical, too. You see him playing the drums in "Life Is Sweet," if you remember. The bonus there was that he and I have got this great shared passion for all things Victorian, and Dickens in particular. In fact, he was in the Royal Shakespeare Company's "Nicholas Nickleby": He was Young Squeers, and he was good. At an early stage, I had him in mind for Gilbert's manservant. But then I had to find a Richard Temple, and the truth was that little is known of this guy except a few material facts. So it left us huge scope to invent this definitive Victorian actor, which is right up Timothy's street. We both, at different stages of our early childhood, secretly wanted to be Charles Laughton. And what Timothy Spall does is a great piece of modern Laughton-esque acting. He absolutely balances on that fine line between the grotesque and the moving.

In retrospect it seems inevitable, but was it always your plan to center the story on the period before "The Mikado," when G&S seem to have split up?

Yes; as you say, it was inevitable. No other point in their history is that interesting. As you know, I always like to tell stories when the main protagonists are up and running, and then you can go off into other directions.

These days, musicals like "Annie Get Your Gun" have to be vetted before each new production, to make sure they conform to contemporary attitudes. That doesn't enter into your treatment of "The Mikado." You do seem to think that there was an open-hearted cultural exchange in what Gilbert did.

Yes, although that's something to deal with cautiously. Because there is a certain degree of inherent racism on the go in certain sections of the film, including the attitudes expressed when the three actors are talking about the defeat of General Gordon at Khartoum. I mean, the fact is Gordon shouldn't have been there, but that's a very modern, liberated, post-colonial point of view.

Interestingly enough, there are in "The Mikado" a couple of references to "niggers," one of which is within Temple's "Mikado" song: "The lady who dyes a chemical yellow/Or stains her grey hair puce/Or pinches her figger/Is blacked like a nigger/With permanent walnut juice." "Blacked like a nigger" was reworked in the 1950s as "painted with vigor." We shot the original line, and there was quite a kerfuffle about it. Then we had to cut a verse anyway from a couple of songs, because we were too long in film time, and out it went. I think we properly dodged what would have been unnecessary hassles. But the line probably would not have been perceived as racism at the time of Gilbert and Sullivan.

And, yeah, the spirit is generally open and generous, if a touch avuncular. It's a kind of local technicality that there are non-P.C. specific elements.

Audiences may get a little nervous at the start of that marvelous scene in which Gilbert has three Japanese women teach the actresses how to walk in "Three Little Maids From School Are We." Especially if they don't know that you're being accurate about what Gilbert actually did.

It depends on what you call being accurate. Certain things I know are fact and with certain others I am taking dramatic liberties. For example, Gilbert certainly brought people from the Japanese exhibition to show his actors how to be Japanese. I have no doubt they came over several days and I personally have little doubt that what happened was entirely functional and straightforward -- they just showed the actors a few things, like how to use the fans.

So what happens in the film is plainly an invented piece, a concoction, and rightly so -- this film is not a documentary. The idea that Gilbert gets the Japanese to demonstrate something and they have no idea what they're demonstrating -- and they don't do anything because they don't know what he wants -- and then he gets other people to imitate them not doing anything -- and that becomes it -- it's fairly preposterous but it makes its own kind of sense, curiously, within the piece.

And incidentally, although we're not talking about it, that scene is absolutely a function of doing the film in an organic way. If ever there was an example of how I achieve things by the way I work -- which I couldn't possibly achieve in a million years with a million monkeys and a million typewriters, or word processors, in a room -- that is it.

Shares