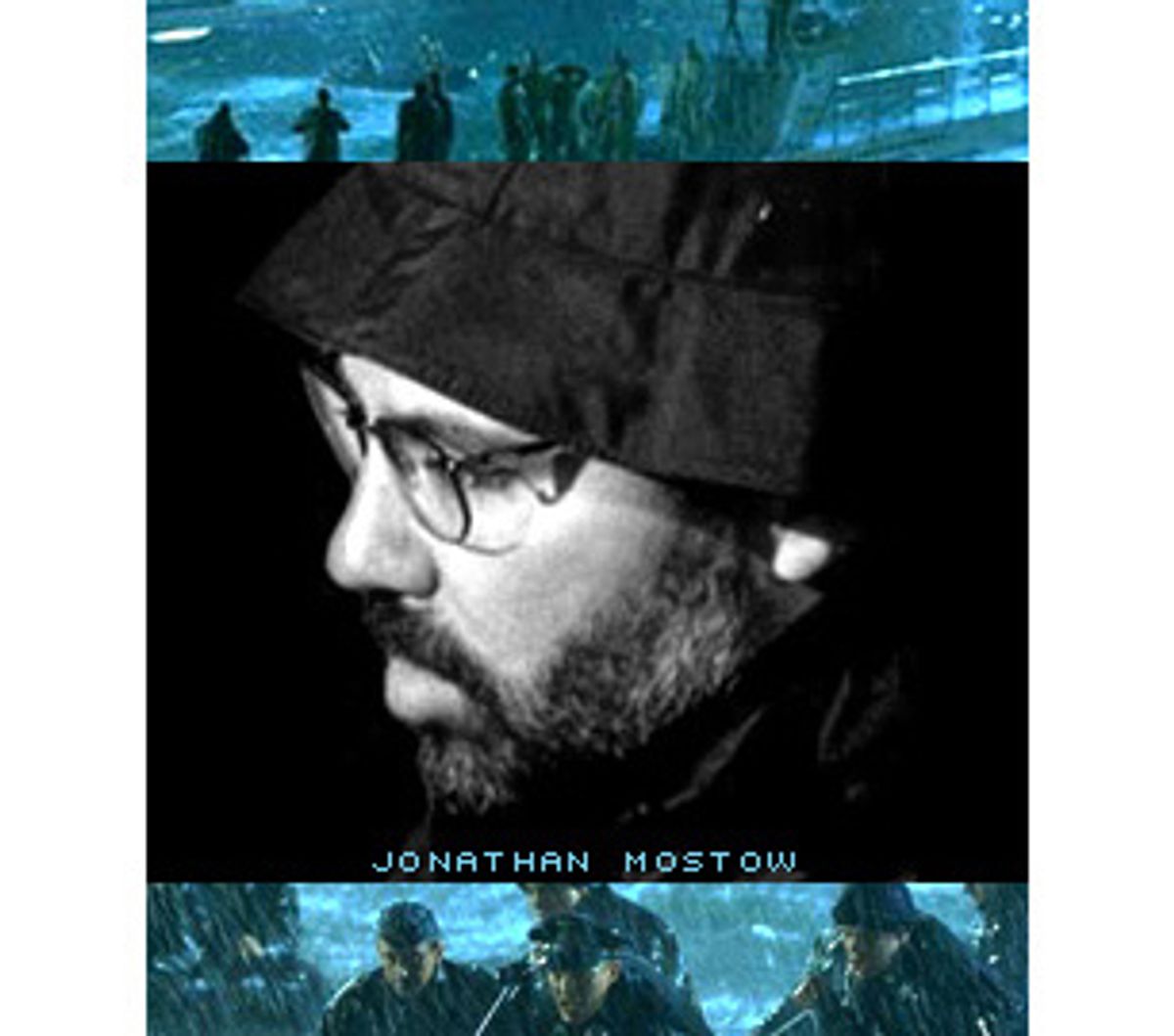

Jonathan Mostow has followed in Steven Spielberg's footsteps in more ways than one. His 1997 debut movie, "Breakdown," is a powerhouse on-the-road suspense film comparable to Spielberg's famous TV movie, "Duel," while "U-571," set in a crippled Nazi U-boat taken over by U.S. submariners, is a high-seas adventure that in its final hour is almost as harrowing as "Jaws."

Of course, because "U-571" is a World War II survival saga that pays tribute to American fighting men, it's more often linked to Spielberg's "Saving Private Ryan." But "U-571" has none of that movie's air of self-importance. Mostow wanted to create a sub experience that was "real" without punishing the audience for its participation. Like Spielberg at his least pretentious, Mostow uses contemporary savvy to revive old modes of entertainment -- in this case, the patriotic yet wised-up military adventure that reached its apogee with "The Great Escape."

A surprising number of prominent directors have sported Harvard degrees -- they range from Michael Ritchie and Michael Crichton to James Toback and Ed Zwick. But Mostow is one of the few to emerge from that university's visual studies program, which has long been linked with avant-garde and documentary filmmaking and structuralist criticism.

When I spoke to Mostow on the phone from his Los Angeles office last week, he explained that he was part of a cluster of entertainment-minded Viz Stud tyros -- including Reginald Hudlin of "House Party" fame -- who managed to graduate in the early '80s without ever learning the meaning of "semiotics." He did do documentaries in college, but his senior thesis was a horror film with an exploding eyeball.

Growing up in Woodbridge, Conn., a small town outside New Haven, in a family of "academics, mostly in the sciences, and classical musicians," Mostow never considered making movies for a living. Even after Harvard, he went to Los Angeles with low expectations: "I thought I'd get a job as a parking lot attendant, and that would be the way to meet people." He sent out letters, and won a meeting with Michael Eisner when Eisner was running Paramount.

He showed Eisner his 11-minute movie and tried to convince the executive that he should be "a story editor or something" -- that seemed "much more doable" to Mostow than becoming a director. Eisner asked, "Why don't you want to be a filmmaker?" It took a while for Mostow to convince himself that calling the shots on a set would come as naturally to him as sitting behind a desk in a suit.

"What I love about Hollywood," says Mostow, "is that there's a great equalizer at work here. No one gave me a break because I had an Ivy League diploma. What people care about is: Do you have a script that I can buy, or an idea for a movie that makes sense? That to me is very American; it's just that, instead of inventing something in your workshop, you're sitting in your kitchen with a typewriter writing a screenplay. And you can go from obscurity to an Academy Award in one shot."

Mostow spent about eight years "outside the business trying to be inside the business," he says. "I taught, I wrote business plans for people in start-up companies, I did any kind of freelance gig where I could control the hours and really be at home writing a screenplay or trying to direct a music video. I did direct a couple of music videos, and worked briefly for Roger Corman, and did some industrial films. Like so many people, I bounced along the bottom of Hollywood, living at or below the poverty line. For a while I fell into being the SAT coach to the kids of the stars.

"The way that I defined success in show business was if you could make a living inside of it, as opposed to driving a taxi to support your presence on the margins of it. Anything after that was gravy. The fact that I could pay my $300-a-month rent by earning a living through using my mind -- to come up with story ideas, or whatever in particular I was doing at the time -- that really, for me, was what it meant to be successful in show business."

In 1989, Mostow made a straight-to-video horror comedy called "Beverly Hills Bodysnatchers." The next year he directed the first feature-length work that he'll own up to: "Flight of Black Angel," an independent production that premiered on the cable channel Showtime. Like "Breakdown," about a lone Easterner fighting for his wife in Southwestern badlands, and "U-571," about a U.S. Navy sub crew pulling off a risky operation in German disguise, it was, he says, "essentially a thriller. A lot of what my movies are about is rhythm and pace."

Mostow describes "Flight of Black Angel" as a "cross between 'Taxi Driver' and 'Top Gun,'" centering on a mentally unstable Air Force pilot. "It was done for $1 million, and it got a lot of attention inside Hollywood because it looked like it cost 15 times more than it did. It had these giant aerial dogfight sequences. From that movie I got an agent. I was meeting with studios and being offered projects, but I just wasn't interested in what the studios were making. So after a year of reading scripts I developed my own project, 'The Game,' which ultimately David Fincher made with Michael Douglas." (Mostow wound up with an executive producer credit.)

"Ironically, that's how 'U-571' came up. I decided to shoot 'The Game' in San Francisco, and when I was scouting locations for it I saw a sign, down near Fisherman's Wharf, reading, 'World War II Submarine Tours, $2.' I went on board and was fascinated by the subject."

How did "The Game" pass out of your hands?

That was an expensive lesson to me, especially in terms of time, about how difficult it is to get a movie together if you're looking for big movie stars and you don't have enough credibility. That picture was at MGM when the studio was in disarray. No star wants to do a movie at a studio that's going through all sorts of problems -- they know the distribution will be questionable. On top of that, nobody had ever heard of me. "The Game" was a movie that required a big star to take a creative risk. In the hands of a successful director, he might want to take that risk, but not in the hands of a person he'd never heard of who'd done one movie for a million dollars. I spent about three years thinking, "Somebody will say yes." Nobody said yes. I did get close to getting Kurt Russell, and that encounter with Kurt later proved helpful in getting him to do "Breakdown."

But that's the only good thing that came out of the process. When you don't do anything for that length of time, your agent will pitch you for jobs, and what you'll hear is, "We liked that low-budget 'Flight of Black Angel' movie he did. But he hasn't done a movie in three or four years. What's the matter with him?"

When "The Game" stalled out, I thought, "Now I'm going to write a movie." I remembered going on that World War II submarine in San Francisco and wondering whether there was a movie there. Of course there was, but it was a big World War II picture set on water -- which was truly a stupid thing to write, because if I couldn't get "The Game" off the ground, how could I set up a really expensive World War II movie? At the time -- 1992, 1993, 1994 -- World War II was not a commercial genre. And the studios swore off movies set on water after "Waterworld."

So as a reaction against that, I thought, "Let me write the cheapest movie I could think of, one that has no sets. We'll shoot it out on the desert, without location permits, and just use available sunlight." That script was "Breakdown." So in a sense all these projects came out of one another. [Mostow co-wrote both "Breakdown" and "U-571" with Sam Montgomery; David Ayer, a former U.S. Navy sonar man, shares the screenplay credit with them on the sub movie.]

Some of the funniest stuff in "Breakdown" is the subtle class satire; one of my favorite moments is when Kurt Russell goes into the bar and tells the assembled rednecks that his wife was wearing a Benetton sweater.

Yeah, exactly.

What makes "Breakdown" so intense is that you don't know whether Russell will be tough enough to rescue his wife from her kidnappers.

The way that I filmed the movie, you become that guy within 10 minutes of watching it. You're having that experience. That's why, three years after it's been in the theaters, I run into people who don't realize I directed it, and when they talk about it they still have an emotional response that's very fresh in their minds. When you can shoot a film from a particular character's point of view, it can be a powerful way of telling a story, especially if it connects, the way this one did, to people's own paranoia and subconscious fears. It touched a nerve.

I think the fear of being lost far from home is a universal fear. I'm sure when we were cavemen, the idea of being stranded far from the cave was terrifying. Then you add in all the urban legends that have sprung into our consciousness, over the last 50 years, of crazy people in broken-down shacks off the highway, who skin people alive who happen to knock on their door.

Both "The Game" [written by John Brancato and Michael Ferris] and "Breakdown" are about characters who learn that man can't live in an insulated environment -- unruly life will always break into it.

In fact, "U-571" is in some ways the same movie because, really, when you're in a submarine, your greatest fear is of the ocean coming into your world. But "U-571" is also about a time when a generation of young men faced the question of whether they would rise up together and risk their lives to defeat an incredible threat or whether they were just going to wimp out. I think what interests me in all these movies is the question of what it takes to get one to rise above one's normal everyday life and do something dangerous and extraordinary.

What's intriguing about "U-571" is that the man you put at the center of it, the relatively untried officer played by Matthew McConaughey, is not a John Wayne character -- he's somebody who'd like to be John Wayne.

I was trying to get somebody the audience would identify with.

Which is why it's interesting -- he's the perfect choice to address today's audience, which hasn't had a tough history and doesn't know if it's capable of what our fathers and grandfathers did.

You know what group "U-571" tests best with? It tests best with women over 30. I mean, it tests great across the board -- we get amazing exit surveys -- but we actually do better with women than we do with men. I was talking about this with a female journalist. She said, "Well, I believe it's because women are always being told they're not good enough. Here's a character who's being told he's not good enough, and he has to be good enough, and women can identify with that." But I think everybody can identify with the scene where Bill Paxton tells him he's not suited for command. Everybody has been told at one point in their lives that they're not good enough.

You put an additional stress on the character when you cast McConaughey, an actor who, perhaps unfairly, became a reference point for premature stardom, who was known for being treated as a star just because he was on the cover of Vanity Fair, before he was ready for it.

That's a good analogy.

What were the biggest challenges of doing an epic like "U-571"?

Actually, one of my biggest challenges was overcoming being stuck in a submarine, where there's no chance to cut away to the restaurant at night, or the farm. You don't have all these devices that help make movies "movies," that allow you to cut away to a radically different location.

And, in production, "U-571" was a movie of extremes. Half was shot on a soundstage, which is a comfortable way of making a movie. It's controlled: You're not fighting the sunlight or the sound of someone running a leaf blower next door, and you have a nice dressing room right there. And the other half was shot out in water, dealing with huge elements.

You really feel the moment when the sub just misses scraping the bottom of the enemy destroyer. You don't have those weightless effects that come with movies that rely too heavily on computer-graphics imagery.

I wish CGI were further along than it is, but it isn't. To me, it does look fake. We do have some CGI, but most of the stuff in our movie is real: It's either done full size or with quarter-scale miniatures -- and we're talking miniatures that are from 50 to 80 feet long, so it's still a massive engineering job to get them to move in the water.

We built a 600-ton full-size submarine, a self-propelled, diesel-powered submarine, as well as a couple of full-size submarine replicas. The fun thing about making a movie this size was going out to sea on this submarine. It was so convincing that when a U.S. aircraft carrier pulled into port next to us one day on the island of Malta, they had to send over a boarding party because we weren't showing up on any of their enemy registries. They were amazed that we did this for a movie.

But for me, the biggest difference between this movie and "Breakdown" was the size of the cast. "Breakdown" was a one-man movie: Kurt Russell was there every day and all the others, with a few exceptions, were basically day players. "U-571" is an ensemble movie. Each of the 15 characters has a persona and a purpose for being there, and you, the storyteller, are constantly juggling them.

Some critics complain that the movie lacks characterization. Actually, there were a couple of scenes which did have more character moments, and they came across as completely indulgent, irrelevant and inappropriate. You watched them and you thought, "Hey, buddy, people's lives are depending on you. Why are you crying into your beer glass? You've got a job to do." The fact is that there's a war and a mission and a specific time clock these men are fighting. Any mistakes they make can mean life or death at any given moment. The point of the film is the overall gestalt of people going and doing something so that we can enjoy the liberties that we enjoy today.

I found your movie a lot more entertaining than "Das Boot."

Look, "Das Boot" is a great movie. The only thing about "Das Boot" -- the fundamental untruth of that movie -- is that it tried to portray its submariners as guys who were just trying to mind their own business, as patriotic sailors, when suddenly Hitler came to power and they were reluctantly stuck fighting for the Nazi flag. In fact, that was anything but the case. These guys were all volunteers who got into the war well after Hitler came to power and were ardent Nazis. There was a heavy propaganda program in Germany that gave going into submarines special prestige and imbued these guys with the sense that they were really fighting for the F|hrer and the fatherland.

These guys were gung-ho and pro-Nazi, and to portray otherwise is basically a complete revision of history. Clearly, near the end of the war, morale was ebbing. But I've spoken to some of our guys who captured these guys at sea, and I asked them what they were like. And they said, "They were real Nazis; they were just like out of the movies. They were blond and blue-eyed and arrogant and thought that their capture was a temporary setback, and that Hitler would come along and blow us back into the ocean."

When you follow a movie like "Saving Private Ryan" -- which is trying to make a statement about war, and does it partly by piling on the atrocities -- does it make it more difficult to direct a World War II film that's more in the adventure-movie vein of "The Great Escape" or "The Dirty Dozen"?

Certain people were pissed off, and let us know in some negative reviews, because they came wanting to see "Das Boot" meets "Saving Private Ryan." And that's not what this movie is. I conceived this movie well before "Saving Private Ryan" -- I was inspired by "The Great Escape" and pictures like that. I remember going to see an early screening of "Saving Private Ryan" and walking out thinking, "Can I make this movie now?" Because "Private Ryan" did change the rules.

The answer I got came from the submarine veterans themselves. It came in two ways. One was finding out that, every year, there's a convention of World War II submarine veterans. And they all come: Guys show up with oxygen tubes going up the nose, wheeling oxygen tanks behind them. They will not be kept away. And this is quite in contrast to infantry veterans, many of whom don't want to attend that kind of event, and don't even want to talk about what it was like in the infantry with their own families -- it was horrific and they want it left behind.

So why are submariners so different? The answer lies in the nature of what they did. If you take infantry combat and you depict it authentically on-screen, you get the first 20 minutes of "Private Ryan." And all you can do as a human being is go, "My God, to what depths has humanity sunk?" Take submarine combat and depict it authentically on-screen, as I believe we've done, and the audience goes, "Wow, that's amazing, I can't believe people did that stuff." But it's not bloody, in-your-face stuff. Submarining in World War II was really the dawn of push-button warfare. You pressed a button and launched a torpedo against the enemy a half-mile away.

When I realized there are people who get together every year to celebrate this kind of thing, I sat down with a lot of them and told them the story of the movie. I said, "This is going to be a sea yarn; here it is." And they all had the same reaction, which was, first, that it was a great sea yarn and, second, that if we got the details of the submarining right, they could show their grandkids what they did. My goal was to re-create their visceral experience of being in a submarine and wrap it inside of this adventure.

The reviews of the finished film that count to me the most have been from the veterans who have watched it. It brings back memories for them: in the details of how the men behave, and the handling of technology, and the relationships of the men and the officers. We had an admiral who was the commander of one of our large fleets crying at the end of the movie.

What was the fictional starting point of the yarn? Was it the idea of Americans disguising one of their old subs as a U-boat, and using it as a Trojan horse [to steal the Germans' secret coding device, the Enigma]?

This came a little ass-backwards, in the sense that I wanted to make a World War II submarine movie first. I did a ton of research. Then I trimmed down to the coolest stuff, taken from the pages of history but reading like it was from the pages of a screenplay -- all about the Battle of the Atlantic and secret codes and crazy plans to defeat the enemy. But I still needed a narrative to weave it together.

The submarine service is called the "silent service" for a reason; it's usually involved in stealth operations. Reading about them kind of gave me the idea for the Trojan horse concept, but it was probably more drawn from the Israeli raid on Entebbe [Uganda], where the Israelis disguised a limo as Idi Amin's limo and landed it at the end of an airstrip in the middle of the night, and drove right into the belly of the beast and got the drop on him that way.

In fact, the British at one point did rebuild a German bomber they had shot down and recruited a team of commandos to man it, all of whom spoke perfect German. The idea was to have them pretend that it was a German fighter plane. The plan was that after the next German raid over Britain, the commandos' plane would start to return with the retreating German bombers. Then it would deliberately crash into the ocean near a German surface ship, so that the commandos would be pulled aboard -- because the Germans would think these were downed German aviators. Once aboard, the commandos would pull out their weapons, shoot the crew and steal the Enigma device.

That plan was authored by a young British intelligence officer named Ian Fleming, who went on to another career. World War II is full of these crazy schemes. The British rebuilt the bomber and recruited the team of commandos (it was right out of the movies -- one of these guys had been left at the altar two weeks before by his bride, literally left at the altar), but they never pulled off the mission. I don't think they could find the right situation.

All your research pays off. Even if we in the audience can't understand exactly what's happening to the sub when a screw pops or a valve is closed, you succeed in making us believe that it's happening the right way.

Exactly. Audiences are smart; they intuit that stuff. You can strip out some of the dialogue alone and it'll read like a copy of Chilton's auto repair manual. But the audience loves that the movie doesn't stop to talk down to them; they can figure it out. It pulls you into the experience, and doesn't dumb anything down.

But there are a couple of narrative gaps that bothered me. I couldn't tell where we lost Jon Bon Jovi's character [McConaughey's best Navy buddy] and David Keith's [the Marine major who trains the submariners for the boarding party].

With Jon Bon Jovi, I made the only true compromise that I had to make to get a PG-13 rating. That was eliminating a shot of his head being decapitated. You do see a quick shot of his death, but it's not a decapitation. I didn't think it violated the integrity of the film to change a decapitation to the violent end of him being hit by some object. And the difference between a PG-13 and an R in this movie is huge in terms of the audience it can reach.

As for David Keith, I did shoot his death and it didn't work. It was an effect that was a little cheesy, and it wasn't possible to redo it. There were 75 other characters dying at the same time, so I thought people would intuit that he died, too. I had no problem with that point when I tested the movie. All I can say is, I thought I had my bases covered. What I take as a good sign is that people cared enough to wonder what happened.

For people who say they don't care about the characters but [wonder] what happened to David Keith, or for people who say that the film is thrilling and suspenseful but they didn't care about the characters, I say, "You know what? It wouldn't be thrilling or suspenseful if you didn't care about the characters."

Shares