The perfect Joe Frank experience is driving down an unfamiliar highway alone at night. You turn on your radio and are greeted by a lush, resonant voice that lulls you into a seemingly simple tale of love: a man at an airport saying goodbye to his wife over the phone, which abruptly turns into a vision of betrayal, alienation and death -- often from obscure disease -- all brought about by some profound personal failing, which is redeemed at the last moment by a nearly transcendent moment of joy.

In the 10 minutes between his first "I love you as much as day we were married" to the end of the story, the man is confronted by an elderly woman having a seizure, his wife's infidelity, a near-fatal collision with an ambulance, a diagnosis of a rare form of cancer and his profound loathing for his own son.

Then Frank will shift the scene and you'll find yourself listening in on a private conversation caught midstream between lovers or strangers, parents and children, patient and shrink, pastor and supplicant. It has no obvious connection to the preceding story, but is so disarmingly intimate -- and, at times, so patently absurd -- that you are left wondering if you can believe what you're hearing. Frank coaxes along a confessional flow of sexual encounters or childhood humiliations that serve as unlikely springboards for the most profound questions of human existence: the need for love, the longing for family or the nature of suffering.

Although commonly categorized as radio drama, Frank's work bears very little resemblance to the stagy artifice of plays performed over air. It is instead a dense collage of scripted monologue and staged improvs that are edited down from hours of raw material to 60 minutes of seemingly spontaneous storytelling. Loops of background music as diverse as James Brown and Steve Reich carry you from one scene to the next, bridging the gaps between Frank's associative leaps.

Even Frank's monologues, which seem to come from a completely unified perspective, result from lengthy recorded telephone conversations with a core group of collaborators who have been with him since his earliest days of radio. These are transcribed, edited and then rerecorded by Frank, who races from his home in Santa Monica, Calif., to the studios of KCRW, his home station, early in the morning, without softening his deep seductive voice with extraneous conversation.

As the titles of his public-radio series -- "Work-in-Progress," "Somewhere Out There," "In the Dark" and "The Other Side" -- attest, Frank wanders deeply into the unconscious, producing Dionysian stories with a fairy-tale intensity whose effect is often funny, disturbing and deeply memorable. You could say that "Joe Frank: The Other Side" presents the nightmares that sunnier, more accessible shows like "This American Life" or "Prairie Home Companion" have when they go to sleep at night.

Ira Glass, the producer of "This American Life," got his first paid job in radio working on Frank's program "Summer Notes" in the early 1980s. "I still have vivid memories of Joe Frank programs that I listened to when I was a teenager and first learning about radio," he says. "I can repeat section for section a program I haven't heard for 18 years. It gets into you and stays with you."

Even today, when Glass travels to promote his own nationally syndicated show, he has a recurring Frank experience. "A listener will start to tell me excitedly about this amazing show they've heard," he says. "There is a car accident and the guy in the accident makes friend with the guy who saves him. I haven't even heard the show but I know it's Joe Frank."

Frank himself describes his show as being about "these private things that go on with people and they think nobody's going to talk about. Where your mind goes and maybe it shouldn't go." His current program, "The Other Side," relies much more heavily on what he describes as "realism," meaning a series of more or less true stories that his friends tell about their lives, rather than on his own monologues. The shows come together by a weekly process he describes as "just pure havoc and chaos." He says, "I have no idea week to week what's going to happen."

Larry Block, an actor whose life has frequently provided Frank with material, says, "It's gotten to the point with Frank where every phone call is potentially a show. He'll say, 'Hold on for a second.' He knew that I knew that he was going to turn on the recorder, and thrived on it. He would make a show out of you and me talking right now. He wants to suck out of me every bit of experience in my life."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - -- - -- - -- - -- -

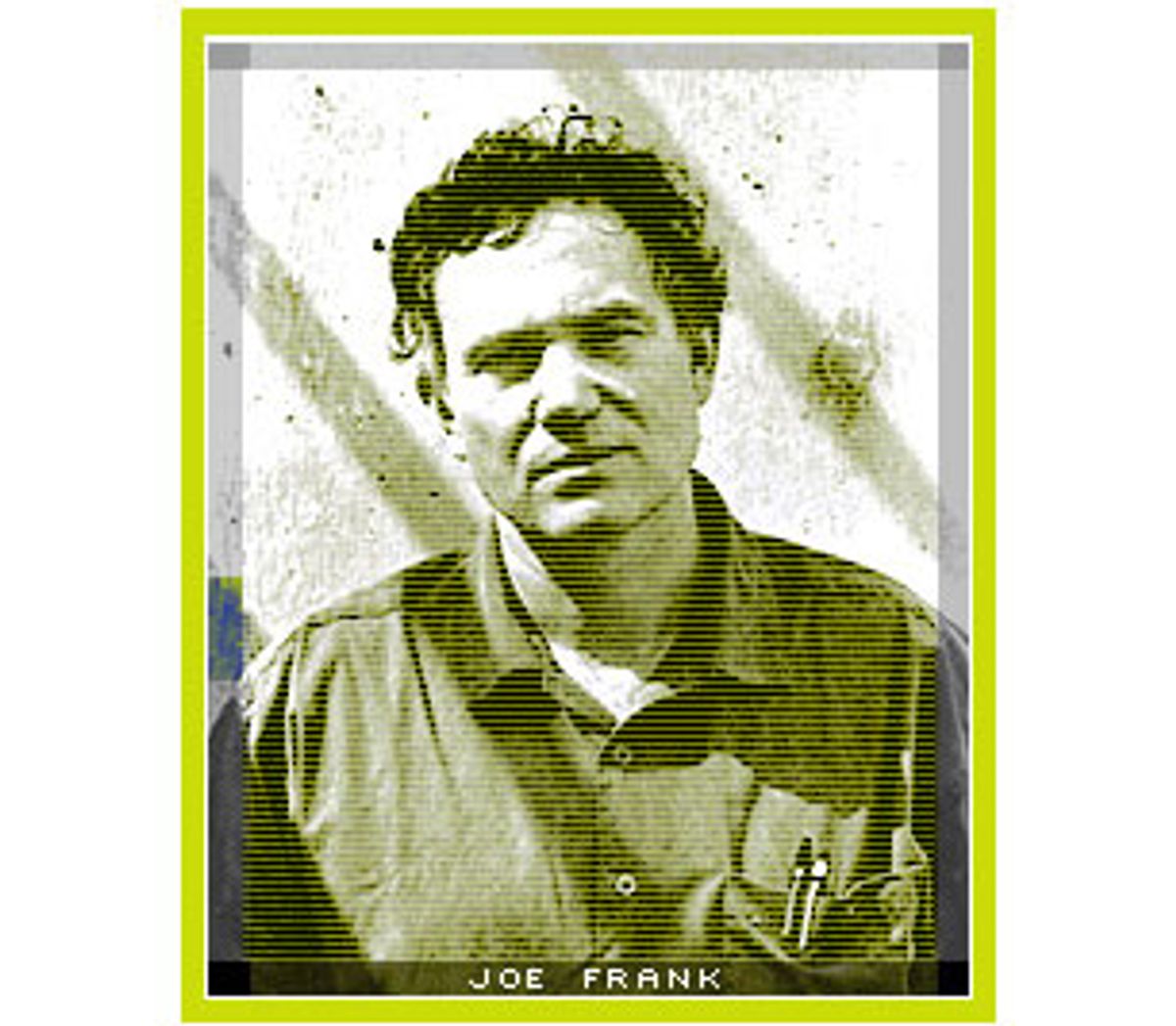

When I meet Frank in person, I feel a little like Dorothy pulling back the curtain on the Wizard of Oz to find that he is not the omniscient being she had imagined him to be. Frank, 61, is a tall boyish mixture of self-assured and mildly embarrassed. His home, an inviting two-story house behind a walled garden on one of Santa Monica's more elegant streets, is nothing like the dark and cluttered domicile where I would have housed his on-air persona. The living room is spotlessly austere and his dining-room cabinet is filled with hard-bound Bibles, Butler's "Lives of the Saints," histories of the world's religion and novels by Kafka, Dos Passos and Faulkner rather than dishes. His office looks like the room where the living is done.

But there's a good reason for the unexpected austerity. The house and everything in it are new, part of a life change that began when Frank abandoned the airwaves in 1998, burned out from the creative and physical demands of a weekly show. After years of living way beneath his means, he finally decided to tap into a personal inheritance that would allow him to live more comfortably than what one could normally afford on a public radio salary. His reason, in a word, is mortality. "You have a certain amount of money," he says. "What are you going to do, die with it?" Two years after his definitive goodbye to radio, he's back on the air, because nothing he did in the interim was as satisfying.

Frank tells me that he's spoken to the people I've interviewed about him and that they've told him about me. He also says that none of what David Rapkin, another longtime collaborator, said about Frank being a "sex god of radio" was true. I can feel myself slide into a world where fact and fantasy commingle in the higher pursuit of an engaging narrative.

His personal history is told through the sepia-toned photographs that line his walls, sealing his European parents and his New York childhood in a distant era. A man and a woman, elegantly dressed for a costume ball, illustrate the happier times of a wealthy Jewish couple forced to flee Nazi Germany. Frank was born in Strasbourg, in the contested provinces along the French-German border. His father came to New York, re-creating his successful shoe manufacturing business in America. He sent for his wife and infant son in 1939.

Frank remembers very little of his father, who died a few years after the family's arrival in America, but his absence hangs over him with a God-like presence, returning to him in dreams and informing the work with a very palpable sense of loss and dread. "We escaped the Holocaust," Frank says. "Although I was very young and I didn't really know what that meant, I grew up in a home where there was a lot of anxiety and misery and a father who was dying while trying to build a life here at the same time." There is a certain painful irony to the fact that Frank, the only son of a prominent shoe manufacturer, was born with club feet, which required extensive corrective surgery. His father died on the eve of the surgery, but Frank was not told until he came home from the hospital.

Although Frank didn't grow up dreaming of a life in radio, he always knew that he could harness a certain imaginative intensity. It was not until he underwent a serious illness in his 20s that he began to read, discovering Faulkner's "The Sound and the Fury" and Dostoevsky's "Notes From the Underground." It was years later, after graduating from Hofstra and the famed University of Iowa Writers Workshop, when he was teaching at a private high school in Manhattan, that he began to be lured by the power of radio.

"The idea of speaking into a microphone and having your voice come out of the speakers of radios all over people's apartments and cars was somehow magical to me," Frank says. "You're hidden, and by virtue of being hidden, there's a power in that."

His first shows, in 1977, were late-night live free-form radio at New York's WBAI, part of the Pacifica network. Frank would talk, play music and direct actors in improv pieces based on stories he found in the tabloids. What would it be like to know your plane was going down in the Pacific? How would you raise a two-headed baby? The idea was to ambush his listeners with a show that sounded as real as possible despite the absurdity of the material.

Arthur Miller, a musician and songwriter whose recurring epithet is "not the playwright," has been one of Frank's most consistent collaborators since the early days. "Joe would come in with all these things he wanted to do. He'd be somewhere between anxious and hysterical," Miller remembers. "There'd be hand-written stuff, typewritten stuff, transcriptions of other people's stuff, things written on the backs of envelopes, in a three-ring binder. He'd say, 'I have scenes with a man and woman, a list of weaponry I want to read, a list of antibiotics I want to read and the music from these three records.' I would help him organize the elements, like acts in a vaudeville show."

In a memorable early collaboration, Frank invited Miller on the air to play a famous mime. After discussing his career, an upcoming date at Carnegie Hall and the pleasures of working with the great Marcel Marceau, Frank asked his guest to perform one of his most famous routines. He let the air go dead for an incredibly long radio minute. When he came back, Frank told the mime that he was wonderful and the phones lit up with callers.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - -- - -- - -- - -- -

After a few years of developing an audience for absurdist late-night humor, Frank was inexplicably hired by National Public Radio as a host for the weekend "All Things Considered." Frank loved the imprimatur of a famous radio program, and was pleased to be paid for the first time in his radio career. But he admits he was "in way over my head" and that the five-minute essays he produced at the end of the hour were inappropriate for the journalistic format. "The kinds of questions I was interested in ["All Things Considered"] didn't answer," he says. "Why are we here? What is the nature of God? If nature is bred with tooth and claw, is human compassion just an anomaly?"

Humorist Harry Shearer, whose own program, "Le Show," airs on KCRW on Sunday mornings just before "The Other Side," remembers Frank's "All Things Considered " days differently. "For 51 minutes it was the regular vanilla news program, only not the usual NPR voice -- less nasal and less vocally constricted," he says. "Then the last five or six minutes of the show was an essay that was like a fist coming out of your radio. It's very rare to have people like Joe -- and I don't want to say that there are people like Joe -- who trust the audience not to freak out." After four months of feeling totally out of his depth, Joe transferred to a new job producing radio dramas, where he did some of his finest programs, including "The Decline of Spengler" and "A Call in the Night."

Ruth Seymour became station manager of KCRW in the early '80s. (The station has since become a celebrated and influential venue of new music and smart talk about politics and culture amid the commercial conformity of Southern California airwaves.) She remembers that every Thursday at 3 p.m., her entire staff would turn up their radios and listen to a program coming in from the network. "I could never get my phone calls done. I'd constantly be yelling for them to turn it down," she says. "Finally, I asked what was happening. They told me Joe Frank was on. Who was Joe Frank?" Seymour went to Washington to investigate. "Joe was sneaking into NPR in the middle of the night to do these programs," she says. "I'd say to him, 'Why don't you come to L.A.? You won't have to sneak into the studio at night. The rest of them are philistines.'"

Frank accepted Seymour's offer, but lived in a hotel room for two years before deciding he was going to stay. In the 14 years he has been at KCRW, through four different incarnations of his weekly program, he has received carte blanche. "No other station manager in the public-radio world would have permitted me on the air," he admits. Seymour says she views the angry letters she gets about Frank's show as a healthy sign of life from audience members who almost never bothers to write when they are happy with the programming.

But Seymour is not foolishly serving the cause of Art. In his first KCRW fund drive since returning to the air, Frank raised more money in one hour than anyone else on the station. During the drive, he exhorts his audience with virulent hate mail and accounts of the humiliations he will suffer if his audience doesn't validate his return to the air by pledging. He pleads with listeners to "open a vein and bleed money our way," inventing such donor categories as "bodhisattva" and "enlightened being" and offering, as a premium, a "Vietnamese monk's self-immolation kit, which comes with a can of gasoline and a pack of matches." An hour later, he has raised $16,635 from a record-breaking 247 callers.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - -- - -- - -- - -- -

Over the years Frank has won most of radio's highest accolades, including the prestigious Peabody Award for his overall body of work. The "Rent-a-Family" trilogy of programs is a good example of why. The story features an imaginary entrepreneurial business that rents single parents and their children to paying clients much the way they would rent a ski chalet for a getaway weekend. "I'd go out to a restaurant and see unhappy families, or on the other hand, happy families. Either way it was very compelling," explains Frank. "If it was unhappy, I was thinking, Thank God I'm not trapped in that. Or if they were happy I'd think that there was a profound human experience that I'm not going to enjoy." He laughs ruefully, adding, "As a bachelor, you could find the ideal family and then rent it repeatedly. But you wouldn't have to live with it and take the responsibility and time required in having a real family."

Interwoven into the "Rent-a-Family" narrative and running as a dark current against its rosy promise are a series of disturbing phone calls made by a woman named Eleanor to her ex-husband, Arthur, who is married to somebody else. She harasses him in the middle of the night with accusations of having stolen her children, which he adamantly denies, largely on the grounds that they never had any to begin with. Years later, when Eleanor's psychotic episode has passed and Arthur's second marriage has ended in divorce, the original couple settles back into a friendship of respectfully complementary psychopathologies -- which suffices for a Frank happy ending.

When I ask Frank about Eleanor from "Rent-a-Family," or the woman in "Soulmate" who leaves an hour's worth of increasingly hostile messages on a lover's answering machine, he smiles and asks, "Is this the misogynist question?" He contends these are the only two women like this in his entire oeuvre, and cites other examples of female characters who are deeply caring and desirable. Most of these, of course, vanish like an apparition moments after they appear, leaving the male character to run through a fast-forward mental scenario of perfect union, reproduction and betrayal.

Over the course of the afternoon, Frank makes frequent references to former lovers and girlfriends, even an ex-wife from his life before radio who called him "poetry in motion." These women, as he tells it, have graced him with their intimacy but have also wrought painful havoc as they've inevitably rebelled against the compartmentalized role they're asked to play in his life.

The level of eroticism runs so high in his programs that recently personal ads have appeared in the Los Angeles papers: "Looking for logic in the irrational, green eyes, 5' 3" slender 31, seeks Joe Frank listener for romantic interlude," or "Somewhere out there is a maverick who is thrilled Joe Frank is back, SWF, 42, 5'5" 125 lbs. playful, sensuous, adventuresome, let's explore the frontiers within." During the years he was off the air, Frank's fiercely loyal listeners found each other in fan-run Web sites and organized electronic swap meets of bootleg cassettes. (KCRW's own Web site archives dozens of programs.)

Frank has also garnered a broad Hollywood following. Filmmakers Michael Mann, David Fincher and Ivan Reitman have all optioned or bought stories from the Frank apocrypha. Francis Ford Coppola, who listens to the show in San Francisco, was signed on to produce a series of Frank stories for HBO, with the appropriately dark Fincher ("Seven," "Fight Club") directing, a project that never came to fruition. Frank was ultimately paid handsomely by producers of a Hollywood film (which he won't name) that plagiarized his dialogue, but there has never been a real Frank feature film. The four shorts made for the Playboy Channel in the mid-'80s don't even approximate the power of his radio shows. He is currently writing a screenplay for William Friedkin, which he laments is taking him away from his obligations to his radio audience.

Most Frank fans are not famous. One of these, a man named Jerry, listened to Frank's dark tales while locked in his New York apartment. After Jerry's death, his brother sent Frank 15 years of tape-recorded telephone conversations -- Jerry arguing with his father, flirting with an ex-girlfriend and reminiscing with his brother, who tries to cajole a cousin out of money for the electric bill. Frank edited the tapes into a trilogy of programs called "Jerry's World," a eulogy of life imitating art and art, in turn, imitating life.

"I don't try to offend anybody, but I do," Frank reflects. "The station gets complaints about me being in the 11 a.m. time slot on Sunday. I like it. There's a large audience. It may seem strange, but I consider my programs religious. It's all about faith, God, meaninglessness."

Frank's version of religion is dominated by anger and questioning rather than acceptance and love. In a program called "Holy Land," he tells Biblical stories -- Adam and Eve's exile from the Garden of Eden, or the Immaculate Conception from Joseph's point of view -- that end up sounding like bad modern marriages. Eve doesn't want to be "just some nature girl" and tells Adam, "Frankly, I resent that God made you first." Joseph says he always knew that Mary "was kind of a social-climber." He's used to watching her work the room at parties, but he "had no idea that she would actually get involved with God." Joseph feels betrayed by a God who would force him to live in infamy as the world's most famous cuckold.

Frank's return to radio is his own mixed blessing. "I've built a body of work on the radio and this is the art form that I understand so I like the idea of just keeping on building," he says. "But it's exhausting and sometimes I feel that my life is rendered empty by the fact that I have to work so hard to create it. It creates a lot of pressure and unhappiness because I feel that I'm not enjoying my life enough. I can't do the things that I want to do because I don't have the time to do them. But then if I do a good program, a program that I'm proud of, it's really complete. Because you can always look back. You can always put that program on and listen to it and it's there. And if you'd gone to the country, you can't put that day in the country on anytime you want. That's not there. This is something that's solid and real and lasting. Even a relationship isn't necessarily that."

For an artist obsessed with mortality and the meaning of life, Frank has chosen the most ephemeral of media. It is fortunate for him that the Web came along, providing a sense of longevity to radio. But as important as his show's digital afterlife may be, nothing compares to the live broadcast, while the audience has temporarily suspended their lives to listen together. Frank tells me he used to sit in his car with a former girlfriend, parked overlooking the ocean, listening to the program as it aired. He sat there imagining his audience in their own cars and living rooms, somewhere out there, in the dark, on the other side of the radio, listening to his life's work-in-progress.

Shares