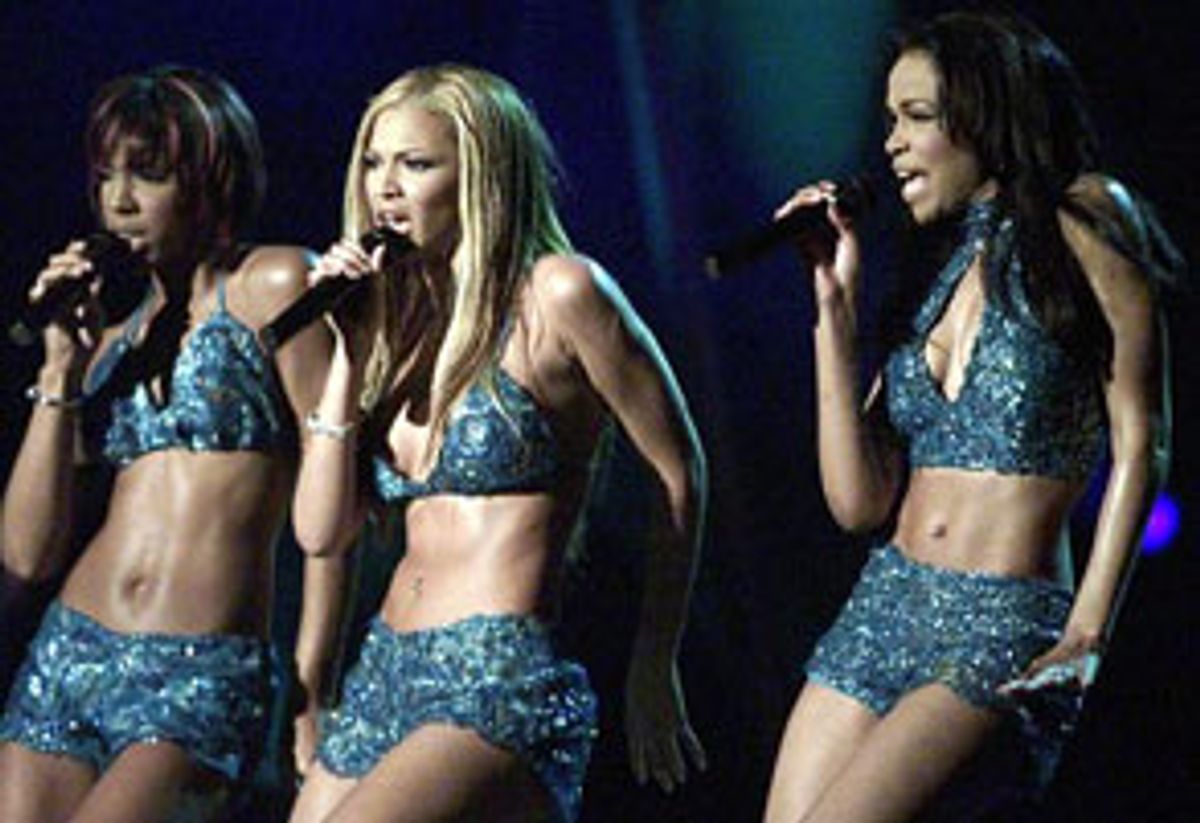

It may be the opening shot in a battle pitting the major record companies against radio's powerful independent promoters. And it all hinges on a song called "Bootylicious."

Industry sources say Columbia Records, the music arm of the giant Sony Corp., is using one of its bestselling acts to send a message to the highly paid brigade of promoters: Enough is enough.

Most listeners don't know that virtually all the pop and rock songs they hear on the radio have been paid for -- indirectly -- by the major record companies. The record labels pay millions of dollars a year to the independent radio promoters, universally referred to as "indies," who in turn pass on a lot of that money to radio stations, which accordingly play what the promoters ask them to.

But the record companies are bridling under ever-increasing costs. In a move that could reverse that trend, Columbia informed indie promoters two weeks ago that the label would sharply curtail its indie payments on behalf of the new single from the multiplatinum-selling girl group Destiny's Child, "Bootylicious."

The label said it would pay $1,000 to indies whose radio stations in only the top 50 markets added the song to their weekly playlists. But the label said it will not pay any indies for adds in smaller-market stations.

This may seem like a minor distinction, but it represents the first time in years a major label has attempted to cut costs in this way. Columbia runs the risk of alienating the powerful indies in the hundreds of smaller radio markets across the country.

Traditionally, indies have been paid whenever one of their claimed stations added a song in any of the nation's hundreds of individual radio markets. And in a major market, $1,000 per song per station represents just the base fee; depending on the circumstance -- like how desperate the label is for airplay -- the fees can ultimately run as high as $5,000 per song.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a source at Columbia downplayed the move, suggesting it's not uncommon for a label to hold back payments on an act as popular as Destiny's Child, since the song's going to get played anyway. "It's not that big a deal. It's not a line drawn in the sand," this source said.

Others disagree. "I've never heard of that," says one veteran Top 40 indie promoter, referring to the top 50 market cutoff. "When I found out I said, 'Holy shit.'"

According to this indie, when a label has a sure thing on its hands it will often only pay for adds that come just the first week the single is released. But all market sizes are covered. "It's a courtesy, an unwritten rule," the indie explains. The rationale for paying indies for songs that stations will play anyway, like "Bootylicious," is that the indies will work harder getting less well-known acts the airplay they need -- or won't try to keep them off the air.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The indies, who maintain long-term relationships with radio programmers and financial alliances with station managers, don't exactly control what gets played on commercial radio. But they do take credit for -- and get paid for -- what gets played.

That influence, real or imagined, has kept record companies at bay. But the companies are now increasingly upset about the escalating costs -- while there are no definitive figures, it's likely labels will dole out more than $100 million, perhaps even as much as $200 million, this year to indies.

But the companies are also afraid of the indies. They're reluctant to confront them for fear that they could retaliate by sabotaging future hits. And without crucial radio airplay, labels cannot reach the mass audience they need to sell their CDs.

That's why Columbia's directive to cut off payment for any station outside the top 50 markets may represent this war's Fort Sumter. Sources suggest it's the first time in years that a major label has tried to dictate terms to the powerful indies.

"It's groundbreaking," says another promoter, who concedes the money-drenched system is teetering out of control. He cheers Columbia's move with Destiny's Child, despite the fact it cost him some money.

"I'll bet you a lot of indies are pissed off, but I got no problem with it. We need a correction and I think this could be the beginning."

Another agrees: "I applaud the Destiny's Child move. Columbia's a market leader with a ton of hits right now. They have the power to send a message and test the waters. To say let's see if it's about the music or the money; let's call a spade a spade. Long term, it could save the industry."

The indie promoter was once just a lobbyist whom the labels hired to help shepherd new songs onto the radio. But those days are long gone. Instead, indies today simply align themselves with certain radio stations, and pay them annual "promotional budgets" of $100,000 or more.

The stations can use the money any way they wish; but once the payment is made, the indies claim those stations as their own -- and bill the record companies for each song the station adds to its playlist.

Indies say they're merely paying for access, a chance to talk to station programmers about playing new songs. But in reality, many radio station program directors hear from their indies just once a week -- on Tuesday afternoon to find out what singles are being added. The indie then calls those adds into the labels -- station A is adding song B -- which triggers the indie's payment from the labels.

"Indies don't work records anymore, they make deals," admits one who's been in the business for decades. "It's like being a salesperson for PlayStation 2 last Christmas. You just take orders."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Columbia's move, however modest, to cap indie earnings comes at a time when there is growing concern among the labels about both the power indies wield and the fees they charge.

Of course, the labels, always searching for a competitive edge, pay the fees willingly, and have only themselves to blame for runaway costs. "Indies are only in business through the benevolence and stupidity of record companies," says one indie who's benefited for years.

Indeed, one need look no further than recent moves by the radio conglomerate Clear Channel, which owns nearly 1,200 U.S. radio stations and controls a hefty 60 percent of the rock-radio market.

Clear Channel has been aggressively looking for ways to make money off its unprecedentedly large radio holdings. There had been talk it would hand its entire roster of music stations over to just one indie firm, Tri State Promotions & Marketing, giving the firm unmatched power to leverage hundreds of Clear Channel stations and generate even more revenue from the record companies.

That appears now not to be the case. Sources speculate recent press attention, both from Salon and the Los Angeles Times, may have dampened company enthusiasm for the deal. Another hurdle may be the different cultures within the broadcasting business; there is for example the tightly knit world of urban and R&B radio, which a pop-promotion firm like Tri State would have a hard time penetrating.

Sources also say two other indie powerhouses, Jeff McClusky and Bill McGathy, might now be allowed to keep some of their current Clear Channel stations.

For instance, a source says McGathy recently bid a breathtaking $3.25 million for the right to represent en masse Clear Channel's 100-plus rock stations. (While the offer probably included some form of upfront lump payment, it still represents a hefty premium over the current industry average of about $100,000 per station.)

"It was a fair market bid," says the source.

Clear Channel countered with a counteroffer that totaled $8 million.

Such moves are viewed with enormous concern by the labels, which are ultimately the source of that money. It's now doubtful McGathy will win Clear Channel's entire rock roster, but rather just a small portion.

But all around, prices continue to escalate. Just two years ago, one indie says, he was able to secure an exclusive relationship with a pop-music station in a top 100 market for $50,000 a year. That same indie recently lost a small pop-music station outside the top 100 markets when a competitor offered nearly $200,000 annually. He says the only way that indie can turn a profit on the station is if he doubles the rate he charges labels for playlist adds.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Will Columbia's "Bootylicious" gambit work?

Any attempt by labels to rein in indies is bound to conjure up a strong sense of déjà vu for record-industry veterans. In 1981, upset about the influence amassed by a group of powerful indies known as "The Network," Warner Bros. and Columbia (before CBS sold the label to Sony) launched a boycott. Like today, powerful indies then were getting $3,000 or $4,000 an add, even though they rarely talked to station programmers. According to Fredric Dannen's 1990 music industry exposé, "Hit Men," the boycott quickly collapsed after the labels' marquee artists -- Loverboy (a platinum act at the time) and the Who among them -- revolted after having trouble getting their songs on the radio.

Four years later, labels were still worried about the suffocating costs of indies. At the time, CBS was spending $12 million a year on indie promotion. Today, some majors spend that much every few months. In 1985 music industry trade group the Recording Industry Association of America considered launching an investigation into indies. If the RIAA found any illegal activity, the labels would have a reason to cut their ties, and save millions.

The investigation was shelved, but labels got the out they needed the next year when NBC journalist Brian Ross, helped along by label sources, aired a sensational report connecting heavyweight indies with organized crime. Soon a federal grand jury, under the supervision of then-U.S. Attorney General Rudy Giuliani, began investigating indie promotion. Then-Sen. Albert Gore Jr. opened hearings on "the new payola." Soon, major labels announced they were no longer using indies.

Over time, the practice reemerged. When it did, humbled indies were getting just $700 an add for a major-market station, not $3,000. And that's where the base rate stayed, well into the '90s.

Recently, those indie fees have skyrocketed. One record label's head of promotion estimates it cost $1 million today "just to see if you have a hit at pop radio."

And there's no way around the system. "Everything on the radio is bought today," says Greg Mull, a former major-market programmer. (Mull was once named Billboard magazine's rock program director of the year.) "If you don't put money on the table, then the record is not going to get going. Prior to five years ago, that absolutely was not true."

So how is "Bootylicious" doing at radio? Two weeks after being shipped to radio, 113 pop stations had added the song, according to R&R magazine, making it among the most popular new songs at radio. By comparison, two weeks into the girl group's previous radio hit, "Survivor," for which all indies got paid, 150 stations were playing it.

This may seem like a smaller number, but there are interesting facts under the figures. Indies suggest that much of the discrepancy can be explained by the expected reaction of a hardcore part of the indie world -- by means of two dozen well-known "put" pop stations nationwide that may never play the song.

They're called "put" stations because they're controlled by influential indies who can "put" whatever they want on the playlists. Those indies may be upset by Columbia's move and may have retaliated by keeping "Bootylicious" off the air where they can. But most of the "put" stations are outside the top 50 markets.

With more than 100 stations already on-board for "Bootylicious," and Destiny's Child's new album still entrenched in the top five on Billboard's album chart, "so far, so good if you're Columbia," says one indie promoter. "They're looking pretty smart, or pretty ballsy."

Shares