In the years following the mid-1950s publication of "The Lord of the Rings," author J.R.R. Tolkien was often plagued by interpreters who wanted to read his three-volume epic as an allegory of World War II or the Cold War, with the disembodied villain Sauron standing in for Hitler or Stalin, and the fiendishly powerful One Ring representing nuclear weapons or space-age technology or whatever.

Though he detested these interpretations, Tolkien offered a truce by drawing a line between "allegory," which placed responsibility on the author, and "applicability," which left readers free to find parallels of their own without pretending to read the author's mind. However, the worldwide success of Peter Jackson's film version of "The Lord of the Rings" has produced a whole new generation of mind readers claiming to understand Tolkien's motives, and opened up another front in the culture war that has long simmered around Middle-earth's frontiers.

When the book's original paperback editions became campus bestsellers in the 1960s, conservatives wrote it off as hippie-dippie pablum, an incense-scented ur-text of the New Age movement. Religious conservatives were suspicious of the book's popularity with rock groups like Led Zeppelin, and its connection to the seminal role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons. But what a difference a generation makes! With "The Lord of the Rings" firmly ensconced in popular culture, Catholic theologians and evangelical activists alike are trumpeting the book's hidden Christian messages. As for the pundits, their successors are happy to claim a story in which good has blue eyes and resides in the West, while evil lives due east and has a really bad complexion. How's that for moral clarity?

It's true that Tolkien's personal politics placed him closer to the conservative line than anything else. The counterculture's early embrace of Tolkien was always comically inapt, though the sight of Bilbo Baggins and Gandalf the Gray enjoying "the finest weed in the valley" can still draw sniggers in the theater. But right-wingers may want to undergo a long-overdue round of soul searching before they lay claim to Middle-earth. In fact, they might be better off giving Tolkien back to the hippies. Unlike, say, "Atlas Shrugged," "The Lord of the Rings" makes for a double-edged weapon in today's culture wars.

The first skirmish in the newest battle flared last year when Jonah Goldberg of National Review Online defended "The Two Towers" against some leftist writers who charged the film with racism because the chief monsters -- burly orcs called Uruk-hai, bred by the turncoat wizard Saruman -- have dreadlocks, dark skin and flat noses. The dispute was a nonstarter because, like their counterparts in the book, the film's orcs also speak with broad Cockney accents and trade insults right out of "Tom Brown's Schooldays." (Fortunately, Jackson didn't follow Tolkien's own description of the orcs: "Swarthy ... like the less attractive type of Mongolian.") But that's nothing compared to the most recent clash, given an acid political edge by the ongoing fiasco in Iraq, and involving members of Jackson's cast: Viggo Mortensen, who plays king-in-waiting Aragorn, and John Rhys-Davies, who plays the stouthearted dwarf Gimli.

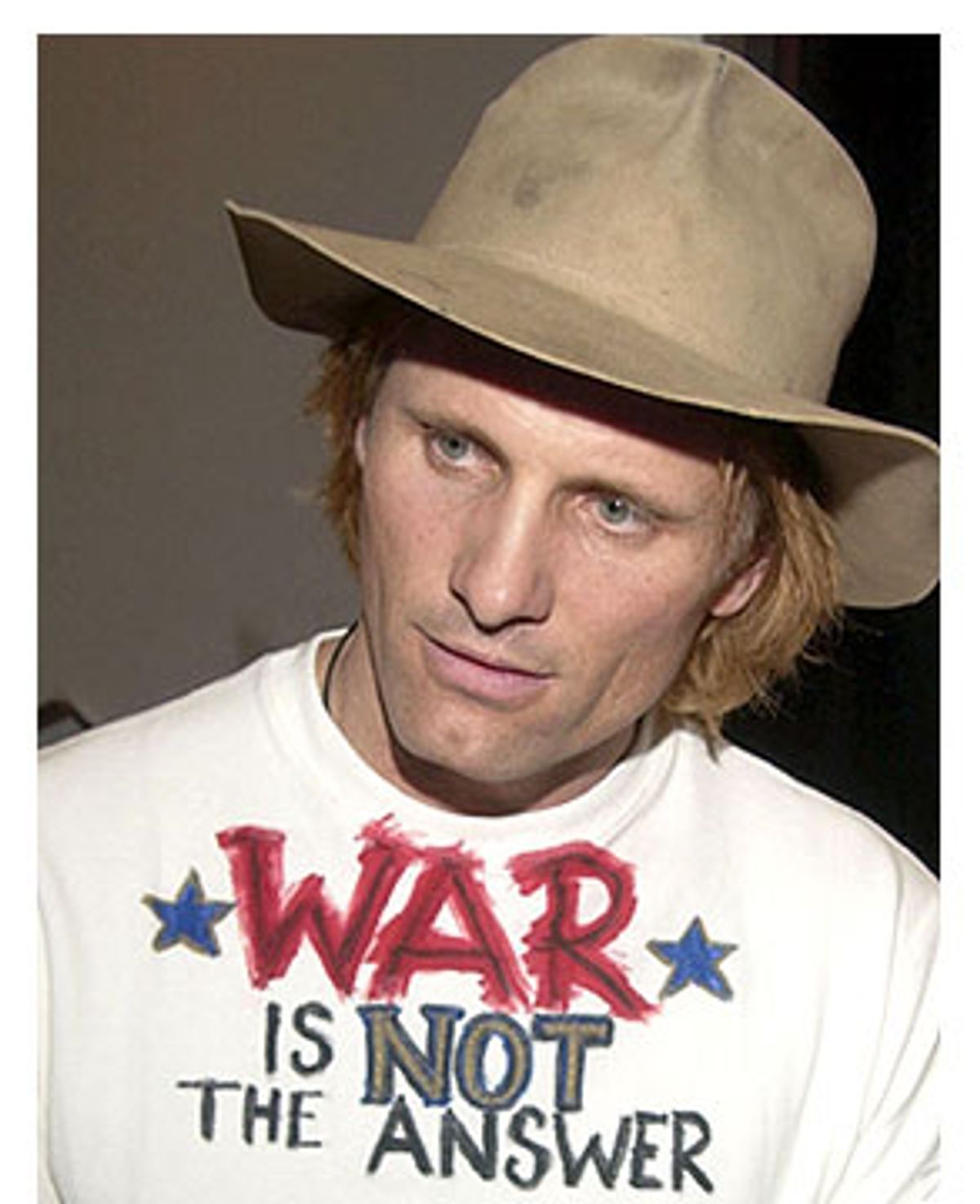

When the first installment, "The Fellowship of the Ring," opened only two months after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, pundits and feature writers were quick to make the War of the Ring an adjunct to the war on terror. During press appearances for the second installment, "The Two Towers," an exasperated Mortensen wore a T-shirt bearing the message "No more blood for oil" and let interviewers know he considered George W. Bush a good buddy of Sauron. Last fall, as the hype machine went into overdrive for "The Return of the King," Mortensen spoke at an antiwar rally in Washington sponsored by International ANSWER, an odious Stalinoid fringe group. Like most of the people who attended the rally, Mortensen seems to have gone in spite of rather than because of the group's involvement -- it's not as though antiwar comment has had so many platforms. Nevertheless, Mortensen has become the piñata of choice for pundits like gay conservative Andrew Sullivan who remain determined to ignore the accretion of lies that fueled the Iraq invasion. (Sullivan, saucy thing, even called Mortensen "cute, but dumb as a post" in his blog.)

Rhys-Davies emerged as a hero to the pro-war faction during a recent press junket, when he offered remarks apparently aimed at Mortensen: "I think that Tolkien says that some generations will be challenged, and if they do not rise to meet that challenge, they will lose their civilization. That does have a real resonance with me ... What is unconscionable is that too many of your fellow journalists do not understand how precarious Western civilization is, and what a jewel it is." Rhys-Davies linked all of it to the rise of militant Islam, and conservative pundits swooned.

Since the interview, Rhys-Davies has been making the rounds of right-wing bottom feeders. On Feb. 19 he spent what looked like the longest hour of his life trapped in Dennis Miller's no-laugh zone on CNBC, doing his best to stay awake while the host and Gloria Allred debated Michael Jackson's fitness as a parent. When his moment came, Rhys-Davies warned that Western Europe was on the verge of being overrun by unassimilated Muslims representing homophobia and other forms of religious intolerance. Since then, of course, George W. Bush -- putative defender of the tolerant values of the West -- has announced he will fight for a constitutional amendment barring same-sex marriages. Sorry, Gimli -- the barbarians are already inside the gates, and they don't pray to Allah. Before we can preach Western values to the Muslims, we have to get the word out to Pat Robertson and his ilk.

But is that really news to Rhys-Davies? A month before his Dennis Miller ordeal, on Jan. 17, the actor consented to share a podium with Michael Medved, the bush-league Bill Bennett who counts up cuss words in movies and types out screeds like his book "Hollywood vs. America." The venue was the Discovery Institute, the Seattle home base of "intelligent design," the slicked-up version of creationism heavily underwritten by conservative moneybags Howard Ahmanson Jr. If the mere presence of some cranks at a political rally disqualifies Viggo Mortensen from serious consideration, then why would John Rhys-Davies -- by all appearances a worldly and cultivated man -- let his name be linked with a group dedicated to injecting theology into science curricula across the country?

The religious angle on Middle-earth, like the political one, was late in developing. Though Tolkien himself considered "The Lord of the Rings" a Christian (and specifically Catholic) work, he took pains to keep overt religious elements well below the surface. Only by digging through the voluminous appendices at the back of "The Return of the King" does one learn that the Fellowship of the Ring's departure from Rivendell -- the beginning of the mission to save all of creation from unredeemed evil -- comes on Dec. 25, while the timing of other plot developments roughly corresponds to the Annunciation, the Crucifixion and the harrowing of Hell. Meanwhile, the pre-Christian ingredients of Middle-earth -- the Elder Edda, "Beowulf," the Icelandic sagas, the Finnish "Kalevala" -- are fairly obvious, as is the affection with which the author uses them. Tolkien's soul was in the Lord's keeping, but his heart -- like that of his friend, C.S. Lewis -- quickened to a pagan drumbeat.

The sound of that drumbeat, along with the scent of New Age patchouli oil, held many Christians at bay when "The Lord of the Rings" enjoyed its first flush of success. The rise of scholarship into Tolkien's Christian leanings began to gather steam in the late 1970s and 1980s, helped considerably by the publication of Tolkien's letters, the 12-volume compilation of working papers called "The History of Middle-earth" and, above all, the posthumous 1977 publication of "The Silmarillion," the endlessly fussed-over private mythology that formed the backdrop to Middle-earth.

As Tom Shippey points out in "The Road to Middle-earth" and "J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century," "The Silmarillion" was designed as a "sub-creation" complementing Scripture -- Tolkien even includes a subtle link between the first appearance of men and the banishment from Eden. The lovely creation story in "The Silmarillion" has the universe sung into existence by the Ainur, a celestial choir formed by the supreme being Illuvatar. (C.S. Lewis, who read Tolkien's work in manuscript, liked this idea so much that he appropriated it for his "Chronicles of Narnia" series.) Just as Lucifer was the brightest of the archangels, so is Melkor -- the satanic figure of Tolkien's universe -- the most beautiful of the singers, and he incurs his fall by trying to make his voice the dominant one. Tolkien has Melkor's discordant notes incorporated by the other singers to form a more beautiful whole. Even the works of evil play a part in the creator's overall design -- a key doctrinal point for Tolkien's Christian advocates, who also point to the depiction of evil as a non-creative force. Throughout "The Lord of the Rings," we are reminded that the orcs and trolls rampaging around Middle-earth are distortions of other creatures, not separate creations in their own right.

Christian analysis now appears to be the dominant mode of writing about "The Lord of the Rings," and enthusiasts are ready to argue everything from the Eucharistic nature of lembas bread to the influence of Catholic liturgy on Tolkien's style. (Joseph Pearce's "Tolkien: A Celebration," offers a good sampling.) Last summer, Christianity Today devoted an entire issue to Tolkien, and a scan of scholarly literature shows plenty of academics arguing for Tolkien's place alongside overtly religious writers like Hillaire Belloc and G.K. Chesterton. Actually, Tolkien's clearest literary antecedents are William Morris, the Victorian socialist and author of medieval romances like "The Well at the End of the World," and Lord Dunsany, the Irish fantast whose 1905 debut, a private mythology called "The Gods of Pegana," could have served as a model for "The Silmarillion." But that's another doctoral thesis.

Nevertheless, "The Lord of the Rings" is viewed with suspicion by many evangelical and fundamentalist Christians, even those who don't necessarily view the pope as the devil's doorman. The alert evangelicals at the ChildCare Action Project cite "The Two Towers" for no fewer than 17 "offenses to God," including "gaiaism" (walking, talking trees -- oh dear), "mockery of the Transformation" (Gandalf's second coming is a bit close to, well, the Second Coming) and "miraculous reverse aging" (presumably the spontaneous makeover Theoden undergoes once Saruman's possession is thrown off). There is also the sticky issue of showing a good wizard (Gandalf) pitted against a bad one (Saruman), when any good fundamentalist knows all sorcerers are bad news. For this reason the Harry Potter books also meet with fundamentalist disapproval, compounded by the fact that they show magical beings mingling with the quotidian world. "Though not as overtly and sympathetically occultic as the Harry Potter series," David W. Cloud warns on the Logos Resource Pages, "Tolkien's fantasies are unscriptural and present a very dangerous message."

Help for evangelicals and fundamentalists alike comes from Focus on the Family, James Dobson's Colorado-based activist group. "Finding God in the Lord of the Rings," written by Dobson associates Kurt Bruner and Jim Ware, offers homilies like "It is never so dark that we cannot sing," lifted from passages in Tolkien and linked (sometimes rather tenuously) to biblical scripture. The film version of "The Return of the King" gets unexpected bonus points from Plugged In, the group's entertainment Web site, because Arwen's decision to have a child with Aragorn at the cost of her own well-being carries an appropriately pro-life message. Part of this accommodation may stem from the ceaseless rear-guard action any strict religious sect must wage against the relentless advance of pop culture. But it doesn't raise Focus on the Family's standing with some of the sterner fundamentalists, who are already suspicious of the group's ecumenical approach to social issues. Reaching out to Catholics, Jews and even Muslims is not going to win favor with these folks, even if it's to deny civil rights to gay people.

Here is where the conservative drive to annex Middle-earth bogs down. Posterity has not preserved Tolkien's views on homosexuality, good, bad or indifferent. But it has given us enough of his other opinions to show that his conservatism was very much an old-fashioned, mind-one's-own-business sort. Even if he disliked gays, Tolkien would not have felt the need to burden others with his opinion. Nor would he have expected the government to go out of its way to deny them the right to marry. With his distaste for industrial society and views on stewardship of the land, Tolkien probably would have been dismissed as a tree-hugger by such deep thinkers as Rush Limbaugh. His preferred mode of government was the gentle anarchy of the Shire, where hobbits tended to their own affairs. Failing that, he told his son in a letter, he would settle for an ineffectual monarch whose interests were model trains or stamp collecting. The neoconservatives and their dreams of remaking the Middle East would surely have met with a great deal of skepticism from the bard of Middle-earth.

For that matter, the invasion of Iraq makes a poor match with the War of the Ring. It only works if we can imagine Gandalf as having cut business deals with Sauron back in the Second Age, even providing him with the seed cultures for breeding his legions of orcs. There is no question of imminent threat in "The Lord of the Rings" -- the armies of Mordor come looking for trouble. Had Gondor marshaled its troops only to find Mordor bare of weapons, and Barad-dur ready to crumble at a touch, then we might find parallels with George W. Bush's grand venture.

Looking back on Tolkien's life, we find his conservatism was rooted in a proper suspicion of power and the motives of those who seek to wield it. This suspicion infuses every line of "The Lord of the Rings," in which the good characters are defined by their wariness of power, while the bad are invariably eager to seize it. One of the many ways Jackson amplifies Tolkien's original comes in the portrayal of Aragorn, fated to become the king of reunited humanity, who spends much of the story resisting his destiny because he doesn't trust himself with such power. Saruman seems to think he can use the power of the Ring to work toward the greater good (a point made clearer in the book), but Gandalf is reluctant even to touch the ring, lest he fall prey to his own version of Saruman's delusions.

Contemporary conservatives, by contrast, are very much enamored of power -- indeed, it is hard to imagine any other way to define them. Certainly none of the qualities that used to typify conservatives -- fiscal prudence, limits on spending and checks against the spread of government power -- can be found in the Republican-run halls of power. All of which should make Gollum, the river-dwelling hobbit who becomes entranced by the Ring of Power and pays for it with his soul, an ominous metaphor. He never hesitates to exploit a wedge issue, be it Frodo's trust of Sam or the distribution of lembas bread, and is savage in combat until defeated, at which point he whines endlessly about how unfair it all is.

Will a similar fate await those who hold the Ring of Power in November? Call it allegory or call it applicability -- either way, many Ring devotees who predate the right's latter-day Tolkien fans would surely find that result more than satisfactory.

Shares