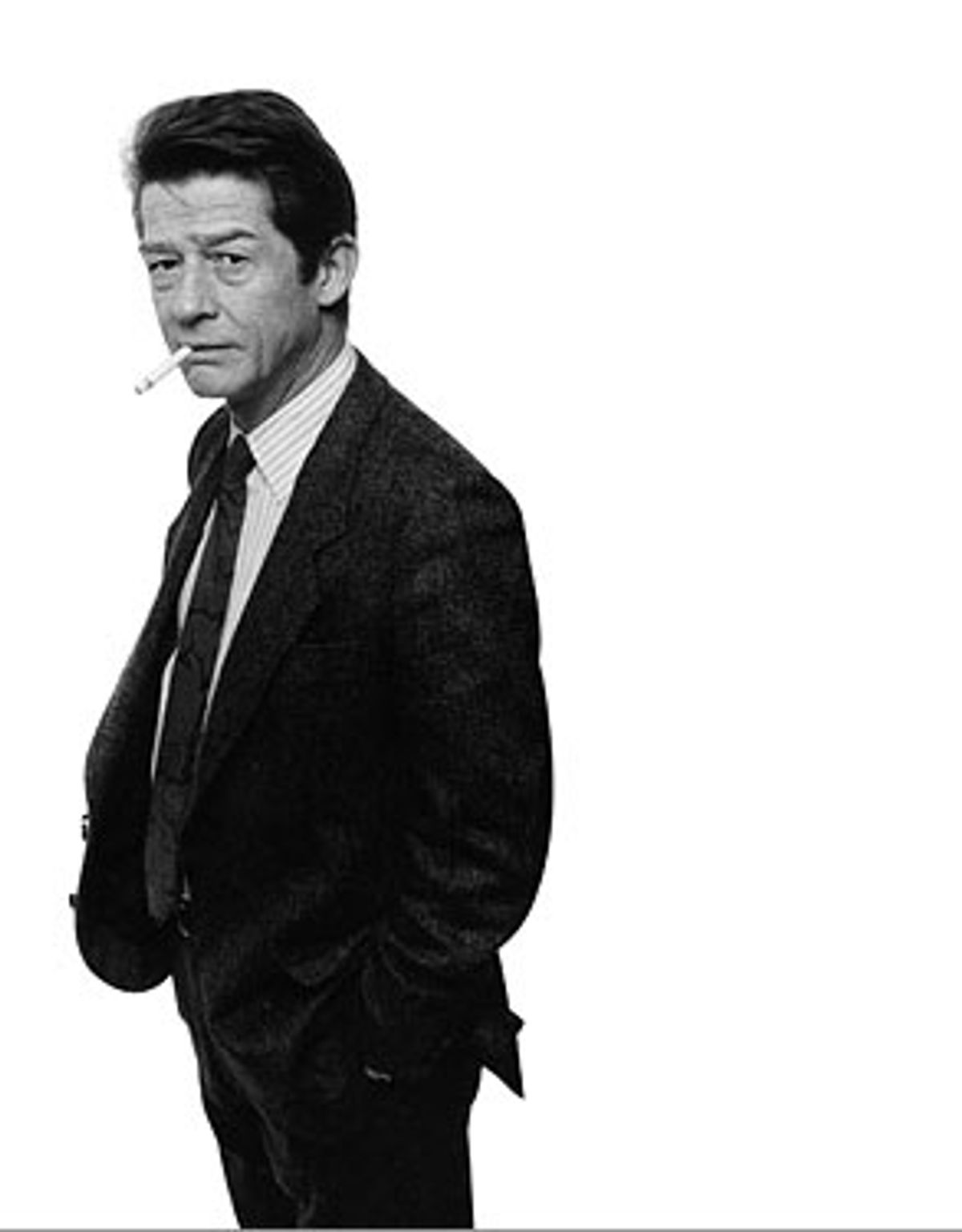

John Hurt shouldn't work as a love object -- it is counterintuitive to the general rules of attraction. His countenance is fishy and bizarre. He has dark, verminous little eyes, a smirky little mouth full of nicotine-varnished teeth, and that British complexion that evokes a poached worm. Even in his early films, he has eye bags and looks like he put on a face that was at the very bottom of his laundry basket. His body, when it isn't a little overindulged around the abdomen, is scrawny. He has never, in any role, looked particularly masculine. The characters he plays are generally weak, immoral, murderous, slimy or insane. Yet to gaze upon John Hurt, in almost any role, is to feel a drooly adoration; he is irresistible.

Men and women both want him, though for what, exactly, I'm not sure -- it's hard to imagine being physically comfortable enough near him to actually touch him. I imagine that his fans wouldn't want to molest him so much as respectfully throw back icy shots of his distilled essence -- a toast, a swallow, and a wincing, hearty aurgh! Hurt is a toxic luxury, delicious as a nasty fruit brandy -- an after-dinner vice of giddy, overpriced pleasure. I attempt, Dear Reader, to deliver you a 180-proof jigger of the exquisite John Hurt. Serve chilled, in the skull of your enemy.

Born in 1940 in Shirebrook, England, Hurt lived until the age of 12 in a small coal-mining village named Woodville. He has described his childhood as unhappy, and his young self as "solitary" and "negative." His father was a Church of England clergyman who thought going to films was "common"; Hurt didn't see a movie until he was 8. He hated what he called his "high anglo-Catholic" prep school, but it did introduce him to his vocation, at age 9, when he was cast as the girl in Maeterlinck's "The Bluebird." Playing the role, as he told Geoff Andrew of the U.K. Guardian (an interview from which I quote extensively in this article) gave Hurt "an extraordinary feeling that I was in the place that I was meant to be."

Hurt had been studying painting at St. Martin's School of Art when he received a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA). This was, most likely, where he was taught his chuggingly rhythmic, immaculate diction; Hurt punches his consonants with the contrast and precision of a teletype -- try to repeat one of his monologues beat for beat, and you'll see what a master tongue-twister he is -- he could probably do macramé with a cherry stem. While still at RADA, Hurt scored his first film role, in something called "The Wild And The Willing" (1962).

His personal life, off-screen, is remarkable (to me) in that contrary to the wry, dry, and effete persona that seems to be his neutral-mode, he is apparently not gay. He appears to love beautiful women, and somewhat steadfastly, if you don't count the handful of divorces, which are generally attributed to his affection for alcohol. He was married from 1962 to 1964 to Annette Robertson, then spent 16 years with model Marie-Lise Volpeliere-Pierrot, a relationship that ended when she died in a riding accident. He was married six years to Donna Peacock, then to Jo Dalton, the mother of his sons Nicolas and Alexander. Hurt, who has referred to himself nonchalantly as "an old drunk," has been publicly sober since 2000; he was most recently paired with Sarah Owen.

Sexual preference notwithstanding, Hurt has always been publicly gay-friendly to the point of speculation. He was one of the earliest English luminaries to champion the AIDS cause; he continually refers to the "Death in Venice"-like "Love and Death in Long Island" as one of the favorite films in his extensive list of credits, and he freely admits to having seen "Jules et Jim" on seven consecutive Sundays -- not exactly rugby, these happily un-macho attachments -- the androgynous question-mark seems to be a brooch Hurt likes to subversively sport on his lapel.

The blurry sexuality Hurt projects is perhaps a result of playing Quentin Crisp so wonderfully in "The Naked Civil Servant" (1975). This film, like a lizard dropped down ski-pants, like a taxi ride through Elsa Schiaparelli 's closet, like a faceful of beautiful pansies, is pure joy. While Hurt's flamboyant poofery is divine, it is Crisp's plucky courage to be so scandalously different at a time when such things were illegal and dangerous that is really affecting; the Dietrich-like dignity with which he suffers fools, the allergy for taking himself too seriously. It is a plum role: a wit, a flower; the weakest of men, externally speaking, but inside, an unshakable tower of firmest meringue.

I first fell in love with John Hurt when I was a kid, watching "I, Claudius" (1976) with my mother on Masterpiece Theatre. Caligula couldn't have done Caligula better than John Hurt did Caligula. How do you make the Idi Amin of ancient Rome come off like a lovable rascal?

Hurt told the Guardian of one contribution he made to the role: "I remember there was a bit of a conflict ... I climbed into bed with my grandmother and thought that this would really be a rather good idea and Herbie (Wise, the director) was getting slightly worried about how far it was going. But after many conversations and discussions we said, Well, how far can Caligula go? And the answer was pretty much as far as possible."

This is one of the handful of times in Hurt's career that he had a script equal to his talent. I live for such lines as this Jack Pulman zinger, when Caligula watches his grandmother die, and gleefully condemns her to hell:

"A goddess?" (Beat. Pleasant, boyish grin.) "... And what makes you think a filthy, smelly old woman like you could be a goddess?"

While Hurt steals virtually every scene he's in by letting Caligula take belligerent joy in causing the extreme discomfort of his peers, my favorite scene of all time is when he rouses his terrified underlings from bed in the middle of the night and forces them to watch a musical number featuring himself as the Rosy-Fingered Goddess, covered with lipstick and syphilis sores. No drag act has ever been performed with more graceless conviction. Hurt's deadpan rivals those of Buster Keaton and John Belushi. It is comic heroin.

Hurt was, by 1978, widely beloved by TV audiences (he has received two British Academy of Film and Television Arts awards in his life, for British TV excellence) but seized mainstream attention for his role as Max, the wise old junkie in "Midnight Express"; this role earned him a Golden Globe and an Oscar nomination, probably because it is some of the simplest work of his career. The 1979 BBC miniseries "Crime and Punishment," though a little difficult to find, has recently been issued on DVD and is the greatest of entertainment luxuries: Dostoyevsky dramatized by Jack Pulman. It is a literally breathtaking piece of dramatic art; at the end shot, which is nothing but a close-up of Hurt's face, crying, I realized that I had been holding my breath until the credits rolled.

Dostoyevsky seems to have been writing expressly for Hurt: Rodya Raskolnikov, hungry, desperate, at the end of himself, his mouth an open black scowl. He may be a murderer, but he'll give all his money to a starving family. It's hard to imagine an actor who can accommodate the enormous emotional span of Dostoyevsky, but Hurt is no prude, and his compassion for the tortured arrogance of Raskolnikov is equal to the author's.

His eyes, before he kills the old woman, are that of a trapped rabbit -- helpless, feverish. He strikes the blows as if they were to save his own life. Morally repellant as the moment is, Hurt has fully inhabited the role -- he embodies wretchedness at its most terrible extreme. He aches to confess, to anyone; he wears the crime like a purulent rash; Hurt forces us to relate to his reckless, compulsive self-endangerment.

Hurt's torment has the fluttering violence of a death rattle; every movement is dictated by inexorable, irreversible stimuli, just as N follows M; his imaginative craft lays the perfect foundation for the point of the pyramid that converges into the sublime.

All this is the more phenomenal when one considers that Hurt didn't bother to read the book until after he shot the miniseries.

"I think it would be very difficult to play somebody if they didn't think they had any virtues or redeeming characteristics. You can play an unlovable character because society doesn't find them easy to love, but somewhere deep inside most people, who do not commit suicide, is a love for themselves."

If Hurt is best known for anything, it is the scene in Ridley Scott's "Alien" (1979) where his stomach explodes in volcanic yellow snot and releases a creature that looks, in Bette Midler's words, "like a penis on a skateboard." Any half-decent actor could have done it -- it was all plastic, writhing and screaming, but something about John Hurt's particular brand of suffering made it iconic. He looks his sexiest and most comestible here, in the first shot of the film, in which he gracefully wakes from his sleep-pod in a large cotton diaper, looking every inch the baby Jesus in his crèche. He seems to be in his prime: fit, sleek, great hair. I love this film, if for nothing more than the epic sets by surrealist H.R. Giger and the image of John Hurt chain-smoking in outer space.

"The Elephant Man" (1980), certainly Hurt's most celebrated leading role, has him so entirely mummified in prosthetics (seven hours of makeup every shooting day) that he must act mainly through his tremulous, pathetic voice and sinus schlucking:

"I ... amb ... NOT ad adimal! (shluck) ... .I amb a humid being!"

But the role of John Merrick is the only one in which Hurt is truly innocent, and he is transcendent. It is already such a moving story: a person outwardly horrifying and inwardly pure, profoundly abused, who retains goodness and refinement throughout his victimization. A Christ figure, the meekest and gentlest of all God's creatures.

John Merrick's alienation from normal society, the pain of the monster, is uncomplicated: the true art of this role is in his terrible, insupportable happiness. When he is rescued from the sideshow, the simplest kindnesses capsize him. He breaks down when a woman offers him tea, because "nobody so beautiful has ever been so kind" to him.

Hurt is overly modest and self-effacing in regard to his craft, which he shrugs off as merely imaginative pretending: "I remember once when I told Lindsay Anderson at a party that acting was just a sophisticated way of playing cowboys and Indians he almost had a fit ..."

He shrugs it off, but when the Elephant Man is given a home, it is a mercy that cannot be adequately put into words, or contained: "My friend, oh, my friend, thank you, oh, thank you, oh, my friend, thank you" -- this is the keening of painfully acute happiness, and an actor of anything less than ingenious imaginative powers could easily have killed it with hack sentimentality.

The real hot poker in the soul is the penultimate scene, when Merrick is taken to the theatre for the first time. It is a classic David Lynchian visual delight: tinselly, Brobdingnagian and sarcastic, but Hurt does the infant wonder in Merrick's eyes to perfection: you are witnessing a man who is gazing at heaven. We can see the wrongs of Merrick's life being abruptly righted, his suffering rewarded; this poor, wretched man-child takes such deep, uncynical pleasure in the flickering paper dazzle of the stage, his heart is miles open, his joy is as insupportably huge as his enlarged skull. Anthony Hopkins practically backs away from him; his gratitude is so intense as to be nearly impossible to accept.

It is the test of an actor's emotional IQ to relate to a being so ... well ... holy. Not everyone can play an unguarded, wide-open soul, naked before love, trusting to the point of Prince Myshkin-like idiocy -- a welcome mat for the brutes of the world to wipe their feet on, but a beacon, lighting the way to the Perfected Inner Man. It is said of the mystic actress Eleanora Duse that toward the end of her career she looked like a small sun onstage; such was the brightness of her spirit.

One could argue that "The Elephant Man" is a shameless tear-jerker, but look closely: Hurt heroically turned himself inside-out; the role is a supernova of compassion, and if he didn't have 10 pounds of rubber on his face, the light of it would melt the screen.

The only role to which Hurt does not seem particularly well-suited is that of a dutiful husband, even when his wife is the incomparable Jane Alexander. The family-man role in Disney's "Night Crossing" (1981) is Hurt's least convincing, but it's not really his fault -- the directing is bad, and he is miscast. While Hurt is peerless at playing a man obsessed, one does not get the impression that he wants to save his children from a dismal life under the commies by flying them over Checkpoint Charlie in a hot-air balloon half so much as he is compelled to endanger them for twisted personal reasons. Were this not an über-formulaic Disney film that insists that you take it all at its dumbest face-value, Hurt might have been playing a father who, loathing the boring demands of his station in life, insists on embarking on a ludicrously dangerous long shot in order to hurl his entire family within shooting range of the Berlin Wall guard towers, in an unconscious effort to get rid of them. Truly, the only scene with any real passion is when Hurt is hollering at Alexander in an effort to convince her to support his plan; he makes her cry by asking (with lots more gusto than is absolutely necessary), "How would you like to see our son's body, riddled with bullets?"

Roll the R, and spit those last three words out with maximum British enunciation, in a vaguely hysterical voice that curls up at the end, like a barrister putting the capper on his final argument: Rrrrriddled with bullets?!" Make sure at least two flecks of saliva are emitted on the last ts, and you may approximate the sadistic oomph with which Hurt rips this one off.

Underneath this ham-fisted, Disney-Dad-Risks-All-to-Save-Family veneer, there is another movie going on in Hurt's eyes -- a movie that asks, What kind of weird, twisted asshole repeatedly risks his family's life and limb in a horribly unsafe contraption, miserable political situation or no?

Jane Alexander regards Hurt, every time the balloon goes down, with a kind of resigned, tightlipped, humiliated fury -- her expression is that of betrayal: Is her husband ballooning toward political freedom, or merely away from the repression of family life? I imagine a private conversation between Hurt and Jane Alexander. You can see the two seasoned actors having a beer together, and Hurt proposing this bit of subtle thespian mischief: doing This but thinking That.

"Bet they don't notice, in the end," you can imagine him saying, of the thick-headed Disney execs.

"I'll bet you're right," she says.

"Oh, let's do," he growls, with that batty twinkle in his eye, unable to resist such high-minded subversion.

"I've done some stinkers in the cinema. You can't regret it," Hurt has said -- no actor with so lengthy a résumé hasn't, but some of his films number among the truly regrettable: "Spaceballs" (1987), "History Of The World Part 1" (1981), "King Ralph" (1991), "Even Cowgirls Get The Blues" (1994). Still, none of these can compare to the great stinker of them all, "Heaven's Gate" (1981)

"Heaven's Gate" is not one of those films, like, say, "Apocalypse Now," where years from its ignominious release, the scales will fall from everyone's eyes and they will realize it was an unappreciated work of genius. Twenty years later, it is still mind-blowingly bad; the pacing is interminable, sienna-toned banjo jamborees make it look like a maudlin, three-hour version of "The Apple Dumpling Gang." Never has so much been spent to suck so much air.

Hurt said of the experience, "I found it a difficult film because I can't bear that sort of indulgence and also it was at a time in my life when I couldn't treat it with a sense of humor ... And I was working with a lot of people who'd worked together before and thought that it would be a very powerful film. It was not an easy time for anybody and it brought a studio to its knees."

While it is absurd to think that one can get an idea of what an actor is like off-camera by one of their performances, Hurt's character, giving an abysmally written valedictory speech to the graduating Harvard Class of 1870 at the beginning of the film, is how I suspect he might have been, at various times in his life, as an actual person: giggly, a little drunk, a little manic, crackling with impeccable comic timing, alternately ebullient and heartbroken. But this is no reason to see the film: indeed, if every copy of it were incinerated, the world would be no worse, but perhaps it is good that it is still floating round video stores as a dreadful object lesson to hubristic young directors with pretentious intent.

"The Disappearance" (1981) is an excessively heavy thriller in which Donald Sutherland speaks in a self-consciously Eastwood-esque monotone. This is a part where Hurt, a junior spy of some sort, looks boyish, but I wouldn't say he ever looks actually young; his mouth is too cynical, his eyes are too insomniac; he always looks like the teen who would have been running the choirboy prostitution ring out of his prep school chapel. He gives the impression, in roles like these, that if he were slightly less talented, he might have been a white-collar criminal.

Although I have tremendous respect for the late Pauline Kael's taste, I think Sam Peckinpah was an idiot, and his filmmaking about as sensitive as an Astroturf condom. "The Osterman Weekend" (1983) is Hurt's most -- uh, physical role. In the first five minutes, his character, intelligence agent Lawrence Facet, is being vigorously mounted by a naked Danish blonde to Lalo Shifrin, proto-Cinemax blow-job music. Hurt's bare, meatless ass exits to the lavatory (his body is like one of those statues of adolescent Hermes -- sprightly, milk-white, toneless) and Mrs. Facet, the horny blonde, is killed by hypodermic-wielding assassins while masturbating. Since this is all captured on film, Facet is driven bonkers and must seek revenge on the parties responsible, blah, blah, blah, whilst watching the tape over and over again in a sicko fashion.

The film is ram-packed with topless, babytalk-dribbling skanks fresh from the toilet stalls of Studio 54 ("Wanna schtupp?" says one; "I bet I could get a little something out of Mr. Tanner. I just coke 'em a little and stroke 'em a little," says another) and Peckimpossible, bourbon-powered caveman dung:

"There's a principle I like to live by: The truth is a lie that hasn't been found out. Maybe you ought to bear that in mind. These are strange times, amigo. But I'm gonna survive. Let's you and me survive 'em together. "

The whole film is sleazy, repellant and absurd, but its most interesting failure was in having cast Hurt as a warm, touchy-feely guy: he tousles a kid's hair, vigorously pets the dog -- it looks very unnatural. Even mid-coitus, Hurt is a frozen fish stick, physically speaking -- he just doesn't read as a big hug guy -- even one who devolves into a psychopath by the end.

In "1984" (1984), as the hapless dissident, Hurt is filled with self-recrimination and moral weakness. It is an utterly joyless life; the small glimpses of happiness he finds are brutally awkward. Hurt's jaw usually hangs open on its hinges, but here it is especially slack; his skin has been allowed to retain its natural pearl-gray oyster tint. It's an excruciating role: He is the ultimate victim, the last vestiges of humanity are tortured out of him, and he is left empty.

From the Guardian interview: "A victim is basically the ultimate of most of us ... It's one of the things that I think cinema deals with fantastically well because it deals with privacy and private moments that are material as opposed to literary and I think it's a wonderful medium to be able to understand more clearly the depths and secrecies of people's lives, and can lead to a great deal more understanding."

"The Hit" (1985), though not particularly successful, is a great film: one of Hurt's favorite projects, and one of his most toothsome roles. He plays Mr. Braddock, a hit man who's lost his inhumanity. He is bloodless and insectoid in his white suit and Cuban-heeled shoes. When feisty kidnapped Latina Laura Del Sol bites his hand, there's an eel-knot of conflicting feelings: he wants to kill her, he doesn't want to kill her, he is surprised by how much he is attracted to her fighting spirit. When she stares at him triumphantly in the rearview mirror with her bloody teeth and spits out a wad of his skin, his eyes show the faintest trace of some strange, bleak kind of invertebrate love. At the very end, Braddock is dying of multiple gunshot wounds when he catches a glimpse of Laura Del Sol, and with the last of his strength, gives her a weak, almost imperceptible, wink.

It is one of the great romantic moments in film, but it's easy to miss completely, it's so, so subtle.

One of Hurt's most charming roles is in "Scandal" (1989), where he plays Dr. Steven Ward, sexual Svengali to Christine Keeler (Joanne Whalley-Kilmer), who ends up touching off the Jack Profumo scandal. When he first catches sight of the sumptuous Whalley-Kilmer (whom no American actress since Faye Dunaway has come near, in the last 20 years, in terms of sheer sexual delectability paired with truly impressive craft. Annette Bening wanted to do it, but Beatty kept her on her back instead. Worse fates could befall a woman's career, but I digress), she is in a floor show. He stares at her and puts a cigarette in his mouth ve-e-e-e-ery slowly, first touching his tongue to the tip of the filter, then, with open mouth, rolling the cigarette around on his lower lip before sticking it in. I can't imagine anyone besides John Hurt and Cher pulling this move off with any marketable sincerity, but it is so eloquent: The gesture tells you in the first 40 seconds of the film that this man is a sex fiend, an opportunist, a charmer, a cad.

His perversions are fun; you want him to be filthy and excessive, because watching him enjoy himself is just too addictive. You want to hear that nasty, cackling laugh and watch the smoke pouring through his teeth, eyes like shiny black slits, smile lines like a dozen parentheses up each cheek.

This character's complexity comes from his sympathetic understanding of scurvy behavior: He forgives moral trespasses easily because he commits them easily.

"You don't care," whines Walley-Kilmer, unfaithful girlfriend.

"Oh yes I do," Hurt says gently. "More than I can say."

You believe that: You believe there are a million strange, icy onion-skin layers between him and everyone else because he has tasted most of life's manifold degeneracies; he has done and accepted it all, Dear, all the orgies, bullets and chemicals and more, simply more, in the pursuit of shameless experience, and your little sins are just too adorable to be of any consequence.

"The Field" (1990), is where Hurt and Richard Harris seem to be competing for Who Can Chew the Most Irish Scenery in a Single Film. Hurt is a village idiot with about seven black teeth in his head, who toadies up to Harris, who is an apoplectic Irish patriarch seething with grunting, red-eyed fury, appropriately nicknamed The Bull.

"Yaargh, aaargh," hacks Hurt, waggling his little fists in support when Harris picks a bar fight. "Yar' tha Boool, yar tha Bool, yar tha Bool!"

About the only thing of value in this film is Hurt's naturally croaky, Long John Silver-ish voice, which he told the Guardian "has been blamed on Guinness and on Gauloises ... but I'm here to tell you that it's a family voice entirely."

Hurt very much enjoyed working with Jim Jarmusch on a small role in the gorgeous "Dead Man" (1995), but perhaps no film enjoys more gushing praise from the man himself than "Love and Death on Long Island" (1997), in which Hurt plays Giles D'Ath (De-Ath -- get it?), an aging, Luddite author who has the embarrassing misfortune of falling in love with Jason Priestly, who essentially plays Jason Priestly, and surprisingly well. This film is ostensibly a retelling of "Death in Venice" for the young and hip, but has many quite funny and smart moments.

We get to see John Hurt crucified by an unrequited fan-love usually suffered by 14-year-old girls. He hides from his housekeeper while cutting out pictures of Priestly from TeenBeat. In a particularly affecting bit, Hurt sneaks a peek at a video of one of Priestly's "Porky's"-esque films. Hurt visibly blushes when watching his secret beloved deliver a tacky line: "You're just a skid mark on the underpants of life! Huh huh huh." Hurt cringes, laughing hysterically -- it is the stab of hot feeling everyone has had watching someone they're in love with do something embarrassing ... then the moment expands, and Hurt giggles, because, on the wings of his great love for Priestly, he can't help but guiltily give in to the lowbrow teen fun. It's a gorgeous little private moment of pure nuance, multi-textured and too subtle for the attitude, dictated by American films, that emotions must be big, hammy sandwiches, slathered in obviousness.

"If you're making a film that is lifelike," sayeth Hurt, "the humor very often isn't something that the character considers to be amusing."

Hurt continues to make films of varying quality, but even in the midst of the dullest concepts, he can bring something to the screen that he hasn't brought before. "All the Little Animals" (1998) is an annoying and unsuccessful film, in which Hurt looks tweedily glamorous, like an aging Samuel Beckett, but is supposed to be playing a mildly psychotic, animal-loving wacko, who forms a friendship with a weepy, brain-damaged, "Willard"-like kid (the truly talented Christian Bale). This is a prime example of the fact that an extraordinarily high level of acting can't save a project that the writer and director are determined to plunge into mediocrity, but Hurt's character is vivid and hilarious when he explains why he loves animals but has no affection for people: "The animals need help! ... Other men kill them, I bury them. I bury rabbits, rats, mice and birds, and frogs, hedgehogs ... .even snails ... .!"

You feel that, indeed, Hurt found a truthful corner of himself that preferred any snail to the most notable human being. The tree-hugging, hippie intentions of the film are good, but ultimately, one would have to be a really stoned or shell-shocked person to endure a film of such oppressive peacefulness.

In "Owning Mahowny" (2003) Hurt has, unlike himself in any of his other films, a deep tan. In a remarkable bit of miscasting, he plays an Atlantic City casino manager. Clearly, John Hurt had no business in this film, but the people casting just loved him, and wanted him to work with him so badly, they didn't care. And really, who could blame them?

I wanted to end with this last quote from the Guardian interview (which I have so ruthlessly eviscerated for my own gain):

Guardian: And who do you see when you look in the mirror?

Hurt: I've no idea who I am anymore. But I cease to be confused about it and frankly I'm not too worried. I'm motoring towards the end of it all in the most enjoyable way and does it really matter if I know who I am? I don't think it does, no. I do see a flicker.

(In addition to the Guardian interview, I have also relied on Dominic Wills' excellent article on Hurt on the U.K. Web site Tiscali. There is also an excellent Web tribute to Hurt accessible here.)

Shares