Does anyone really care about any of the upcoming summer blockbusters? Sure, Alfonso Cuaron stands a good chance of finally rescuing the Harry Potter series from the numbing "faithfulness" of Chris Columbus. And something that turns out to be much better than anyone expected will sneak in and surprise us, as "The Italian Job" and "Freaky Friday" did last year, and as the wonderful "Hellboy" and "13 Going on 30" have done in the run-up to this year's summer movie season. In August, American audiences will finally get to see Zhang Yimou's martial-arts drama "Hero, which may be the best movie you'll see this year and the next, and in July, Richard Linklater releases "Before Sunset," the sequel to his "Before Sunrise," one of the most exquisite romantic films ever made. (So, by the way, is the sequel.)

But facing the glut of the next few months, is there anything coming out of the studios that any of us face with the prospect of real excitement? "Catwoman"? "King Arthur"?

It's worth noting that even the word "blockbuster" no longer even means what it once did. Once upon a time, it was a superlative used to describe a film that succeeded beyond all (usually financial) expectations. In that sense, it's still accurately used for, say, "The Lord of the Rings" movies, which surely deserve to be thought of as blockbusters. But now it is indiscriminately applied to every empty, expensive action movie out there. The word has been "liberated" from its factual meaning to become just another weapon in the publicists' arsenal, a way of referring to the size of gargantuan productions -- regardless of how they eventually do at the box office or what kind of critical response they receive. And the media dutifully swallow the line.

We're not even into June, and already predictable patterns seem to have emerged. "Troy" appears to be this summer's respectable middlebrow entry, as "Seabiscuit," "The Road to Perdition" and "Saving Private Ryan" were before it. Its sudden emergence as this year's "adult" summer entry is thanks to a passel of "it's not bad" reviews. (Not bad? One of the core myths of Western literature and Western civilization starring Brad Pitt and directed by the snooze-inducing Wolfgang Petersen?)

More and more, the prospect of sitting through the big summer movies seems like a chore to be gotten through, and often with less of a sense of accomplishment and pleasure than other summer chores -- installing the air conditioners, say -- promise. Twenty-five years ago, even though "Star Wars" had begun the reduction of American commercial movies to infantile, formula-driven spectacle, there were still summer movies that felt like something to be excited about -- "E.T.," "The Empire Strikes Back," "Superman II" -- that would open, and stay around for three or four months (longer in some cases). More important, for the duration of their theatrical runs, they seemed like news, not something we'd see on a marquee a month later and ask, "Is that still playing?"

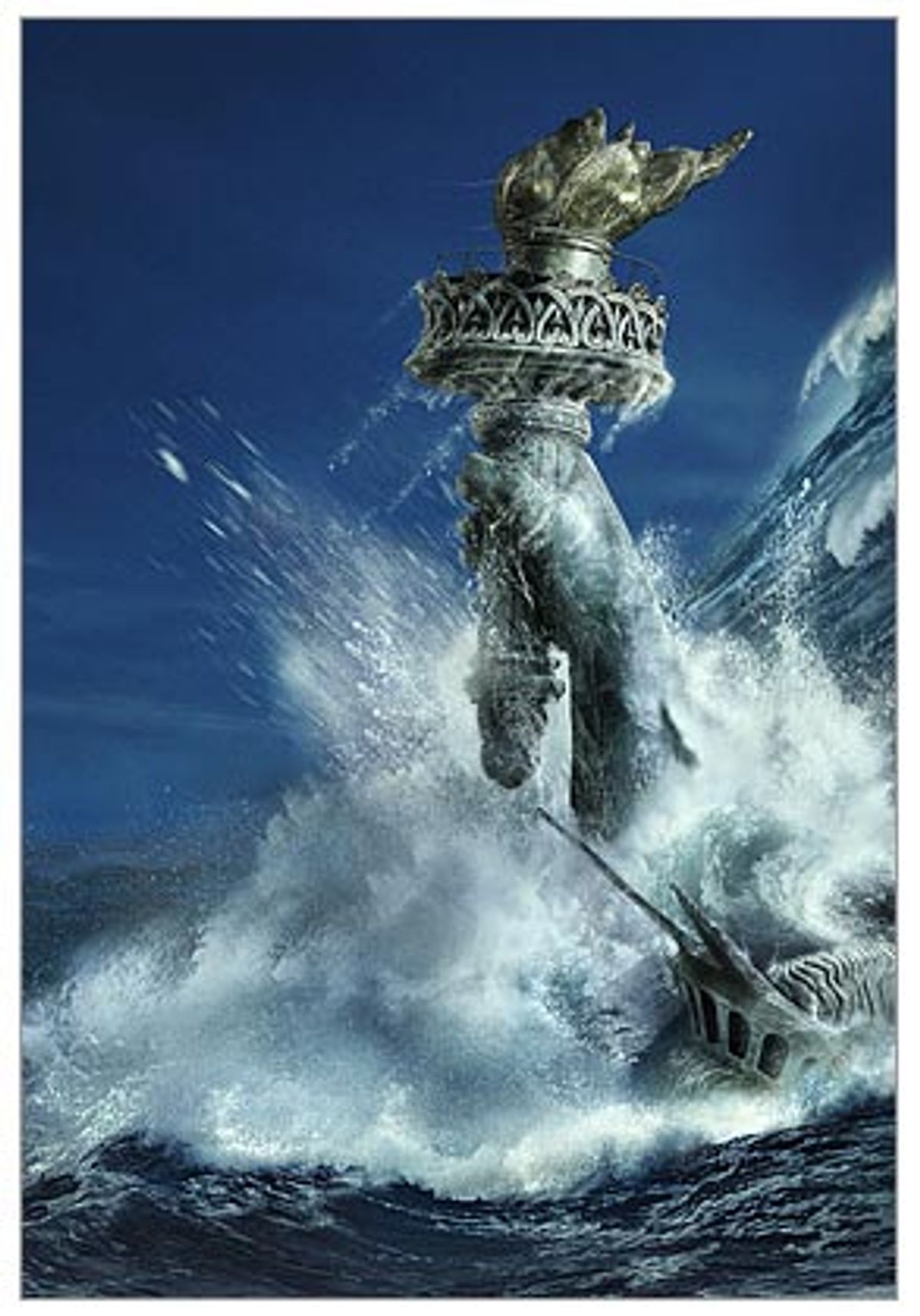

It's no news to say that most of the big summer movies of recent years have been made without any real trace of craft or spirit. The people behind these movies act as if their job was solely to get you to hand over your ticket money -- actually sitting through the movie appears to be an afterthought, and most movies look as if it is. But even though most of us know it, we're still susceptible to the perniciousness of the hype machine, the nagging feeling that we'll be out of it if we don't go see "Van Helsing" or "The Day After Tomorrow" (which, I admit, I have no intention of seeing; 9/11 ended my appetite for watching mass destruction for kicks).

We expect studios to go all-out hawking their wares. But that hype has bled boundaries of TV commercials and billboards and posters. The recent plan (vociferously shot down by baseball fans) to put the Spider-Man logo on bases is just the most obvious example. The absence of the Spidey logo on a few pieces of white rubber isn't going to matter much when Tobey Maguire is being profiled in every magazine and making the rounds of the talk shows. What has become especially insidious about the full-on hype is that it has even taken over the one place that is supposed to stand as an alternative to advertising: The press. The press has always been somewhat willing to kiss the asses of the studio publicists for access to the stars. But the people who call the shots in the arts coverage in the media are, more than ever, acting like those people who are afraid they'll seem out of it if they don't see "Troy."

The formula began with the 1975 release of "Jaws" -- mass openings which allowed movies to recoup much of their cost in the first few weeks -- and has accelerated to such insane rapidity that even the public is in on it, and most highly touted movies are old news by their second weekend in release. If you wanted to find out how much a movie had made over the weekend, you had to look in "Variety," and no one outside the industry was doing that. Now the weekend grosses are reported on Sunday evening newscasts and in Monday morning papers. It isn't just agents and publicists who can say how much a movie dropped over the weekend, it's the casual moviegoer. And by Monday, even the new movies with the biggest weekend openings have begun to be shunted aside for coverage of the upcoming weekend's blockbuster. In the space of three weekends, "Troy" can go from being celebrated for opening big to being declared a bit of a disappointment -- though what movie wouldn't be considered a disappointment when the yardstick of success is the $100 million-plus opening of "Shrek 2"?

For a highly promoted studio movie to open in the No. 1 box-office position is about as difficult as packing a barroom with a "Free Beer" sign. It is rare when a movie holds the No. 1 position for several weeks, as "The Passion of the Christ" recently did. But that movie benefited from the shrewdest (and in some ways, most cynical) ad campaign I've ever seen -- one designed to bring out the faithful and keep them coming out. Most movies, even very successful ones, begin to lose screens and show times by even the third weekend of their release, because of the sense that they no longer have the urgency they did when, say, the star was on the cover of Newsweek. It's a sense that's promulgated not just by the media's obsession with news cycles, but by the idea that all stories last a finite -- and increasingly short -- life span, that the public "tires" quickly. (On the May 16 edition of CNN's media-review show "Reliable Sources," for example, Time's Mark Thompson compared the Google hits on the Abu Ghraib story for the previous weekend [3,000 at any given time] to the hits as they stood a week later [600-800 at any given time] and concluded that this was a story "in decline.")

People also no longer care much if they miss a movie they wanted to see in the theaters since, in no time at all, there will be plenty of other ways for them to see it. In most major cities, you can buy a wretched bootleg of a new movie the day after it opens. Slightly higher up the aesthetic scale, you can see it on pay-per-view in your home or in a hotel (though probably shown in the wrong aspect ratio) a few months later, sometimes while it's still holding on at a few screens. And not long after that, the same movie that generated such hype just a while back will come out on DVD and be reduced to background noise projected on the screens of media megastores where consumers are given the choice of buying it in the correct widescreen format or in the falsely named "Fullscreen" edition, which actually gives them less of the picture. Every Tuesday at the branch of the national electronics chain in my neighborhood you can see customers with a stack of that day's new releases under their arm. Nobody ever seems especially excited about any one release. The buying appears indiscriminate, and you can count on seeing the same folks doing the same thing on the following Tuesday.

The inevitable cumulative result of relentless movie coverage (that has become indistinguishable from publicity), and of a home-video market that reduces every movie to something to be acquired, is to convey the message that no movie is worthy of our sustained attention because in just a few days something else will take its place.

Editors don't need to be corrupt or on the take to play into the hands of the studios. Fearful of losing readers by appearing out of the loop, newspapers and magazines (and, yes, online publications) give each weekend's new blockbuster the prime spot in its movie coverage -- no matter what the publication's critic has to say about it. Put it this way -- if two movies are opening on the same Friday, one a hyped-to-the-skies turkey, and the other a smaller picture that the critic loves, the smaller movie will need all the help it can get. Editors justify this by claiming their readers are interested in the blockbuster. But all that means is that their readers have been exposed to publicity on television or billboards or bus and subway ads -- just as the editors have. Editors who claim that readers won't be interested in smaller movies never seem to answer two questions: 1) How can you determine readers will not have an interest in what they haven't heard of? and 2) Shouldn't informing readers about what they don't know be part of the media's job?

It can't be, though, when the media are acting as de facto publicists. We all laugh at the old movie trailers that sound a lot like "Years in the making! With a cast of thousands!!" But how are interviews where a star talks about how much he worked out to prepare for a role, or where the director or producer talk about the size of the budget, any different? The most insidious thing about covering movies in this way is that often, by the time there is something significant to say about the movies -- after they've been released and the public has engaged and begun to discuss them in meaningful ways -- they are deemed to be no longer of interest.

When hype dictates what is and isn't important, when knowing how to characterize a movie has become more important than responding to it, a movie doesn't have to be an indie or art-house movie to be crushed by the blockbusters. It can happen to good mainstream movies. "13 Going on 30" has done respectable business, but if what's really significant stood a chance of being covered, then the true movie excitement this spring would be Jennifer Garner's performance, which is one of the most lyrical to ever grace any American screen comedy. When movie coverage is focused on the spectacle of blockbusters, no one pays much attention to the beauty of Guillermo del Toro's "Hellboy," a narrative shambles and, visually, a Gothic tone poem about sin, redemption and lovers defying the gods to be together. (Ron Perelman and Selma Blair make most of the actors in "Troy" look like something that came out of a cereal box.)

As in recent summers, the blockbusters of the next few months are likely to leave us feeling like kids who awaken on Christmas morning to find the toy they'd dreamed of is a shoddy spit-and-paste job, tossed aside and forgotten before the week is out.

If there's an irony to the way disposability has taken over movie culture, it's how TV is still blamed for the junkiness that most contemporary blockbusters embody. TV is still accused of being juvenile, and contributing to shortened attention spans. But watching TV, even when I'm just grazing from channel to channel, I'm often struck by how much of what I see is better than most mainstream movies. I'll be lucky if I see a movie thriller this year with the craft or suspense or the punch of the recent "Prime Suspect 6: The Last Witness." And that's not even the most ambitious thing out there. Since series are no longer self-contained episodes but long narrative arcs, it's harder and harder for the casual viewer to join them in the middle. Viewers who follow a series are sometimes committing themselves to four or five years of devoted attention to one narrative; it's even more of a commitment than the one made by a reader who picks up a 19th century novel.

To watch a show like "Alias" or "24" (at least the first two seasons), viewers have to be able to follow a sophisticated level of narrative complexity -- and often visual complexity -- that movie audiences seem no longer able or willing to. "Alias," like "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" and "Angel," shows that the best pop entertainment is taking place on the small screen instead of the big one. These shows proceed from silly pop premises -- a teenage girl who fights to save the world from vampires; a coed who's a double agent working for the CIA -- that, because of the level of emotion packed into them, seem anything but silly. They're emotionally and narratively satisfying in the way that great detective movies or horror movies or noirs can be.

I sometimes think that the only people who pay attention to all those spam e-mails about how "size does matter" are the people running the studios. Summer blockbuster season seems to have become about increasing the size of the product, the size of the hype, and, of course, the size of the process -- all the while reducing the time anyone has to savor or respond to what they're putting out. The effect on movies seems to be similar to the ones steroids are reported to have on genitalia -- as they become bigger and bigger spectacles the movies themselves are shrinking. And when it comes to quality pop entertainment, TV is making the biggest screens look puny.

Shares