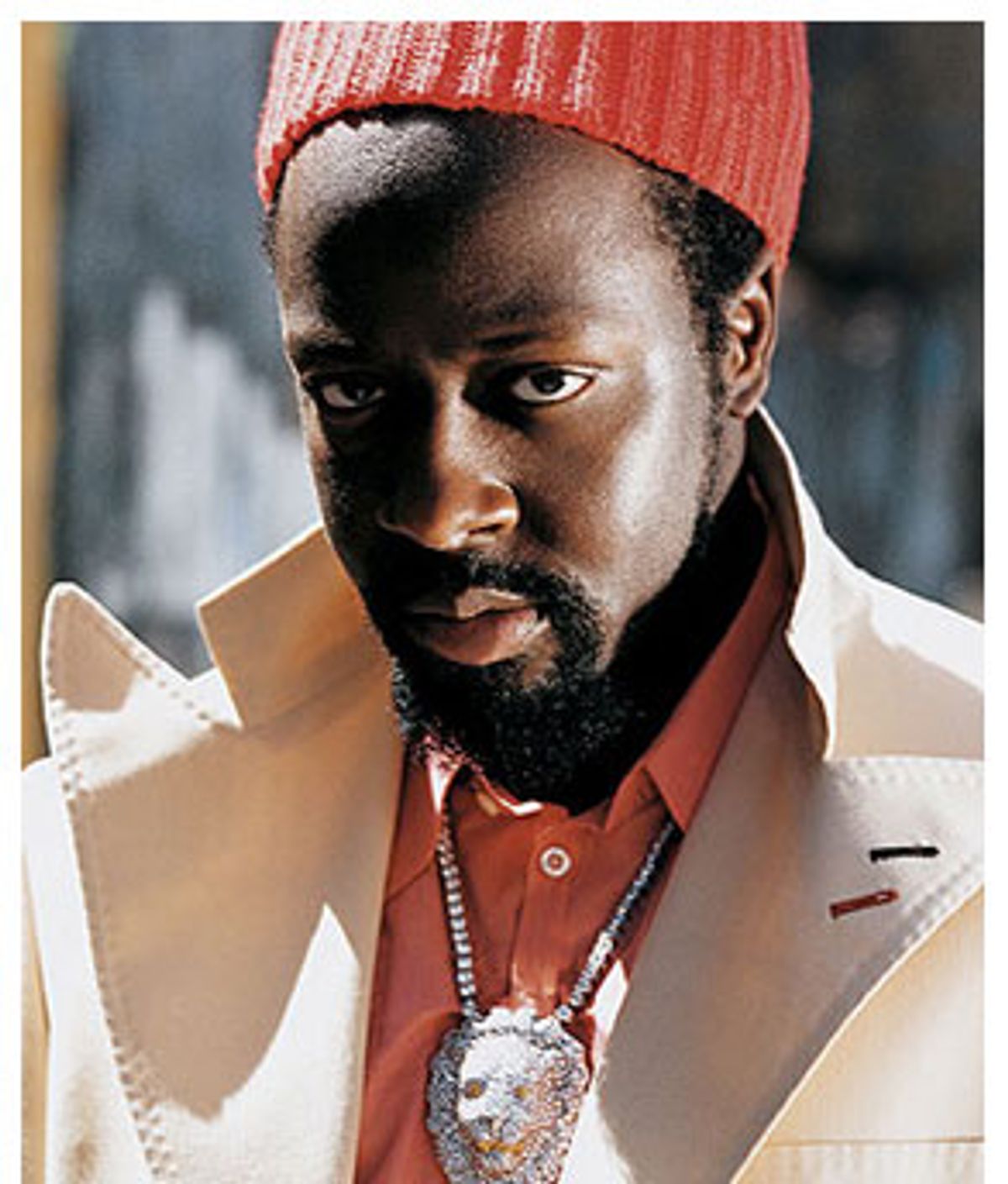

Wyclef Jean is not a great rapper, a stellar singer or a humble self-promoter ("I want to do things that will change people who hear it 300 years from now, like Scriptures," he recently told MTV). That he's favored by two former presidential hopefuls -- Al Gore, who gave Jean a public "shout-out" in 2000, and Howard Dean, who deemed him "fantastic" -- doesn't bode well: Any act deemed fit for political endorsement is likely to be as cutting-edge as warm milk.

Jean's excruciatingly righteous new single, "If I Was President," released via AOL Music, isn't likely to boost his hardcore hip-hop credibility, either. "If I was president," the rapper begins, "instead of spending billions on the war/ I'd take that money so I could feed the poor." The well-intentioned, musically bereft track has the feel of a grade-school writing assignment -- "what would you do if you were president, Billy?" -- and AOL has, aptly enough, turned it into one: Fans are invited to add their own "If I Was President" declarations to an online message board; winning entries will be incorporated into a remix of the original Jean song.

I recently heard an industry rumor, though, that amounted to a challenge: Spend some hours with Jean at his Platinum Sounds studio and try to emerge without being converted to the belief that this utterly imperfect artist -- heavy on political correctness, light on hit songs -- is one of the greatest acts in hip-hop history.

That challenge, combined with an interest in his most recent album, "The Preacher's Son," landed me at Jean's midtown Manhattan studio on a chilly New York afternoon. Jean, sporting slack jeans and an Expos jersey, shakes my hand vigorously. Then his cellphone rings. He flicks it open. "Jonathan Demme!" he sings to the voice on the other end. Jean, 31, considers Demme, the Brooklyn-reared director, his "adopted father." The pair recently worked on "The Agronomist," a documentary about a murdered activist in Haiti for which Jean -- raised in Haiti and known for being outspoken about the politics there -- composed the musical score.

"Yeah, we're at 60,000 a week," Jean says into his phone. "But you know Clive -- he ain't gonna stop until it's a million." "Clive," of course, is legendary music mogul Clive Davis, now head of J Records; "60,000 a week" refers to "The Preacher's Son," Jean's J Records debut and his fourth solo album.

"It's all good," Jean continues. "It's moving like a Wyclef Jean record -- a longevity type of thing."

A Wyclef Jean record does not, after all, move like a record by the Fugees, the group Jean launched with Lauryn Hill and Prakazrel Michel (aka Pras) during his high school years in New Jersey. In 1996, the Fugees released one of the most artistically and commercially successful hip-hop albums of all time, "The Score," which has sold more than 16 million to date.

After the Fugees broke up, Hill released an opus, "The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill"; Pras released little worth noting; Jean released a bit of both, launching a career that's spotty, persistent and ultimately hard to pin down.

He's produced brilliant tracks for the likes of Whitney Houston, Santana, Mick Jagger, Sinéad O'Connor and Destiny's Child. And combined sales of Jean's first three solo albums, he informs me as we take a seat in the studio, have recently hit the 10 million mark. His first solo album, "Wyclef Jean Presents the Carnival," went double platinum and earned him a Grammy nod.

But Jean's next two albums, "The Ecleftic" and "Masquerade," boasted no such commercial or critical success. They did boast an unusually assorted supporting cast: Rappers made their appearance, yes, but so did Kenny Rogers, Tom Jones and Youssou N'Dour. There was a reworking of "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" and a cover of Pink Floyd's "Wish You Were Here." Lyrics came alternately in English, Caribbean patois and French Creole, Jean's original tongue. Jean's diversity has ultimately been his blessing and his curse.

"You never know what I'm gonna do, so you always give me that 10-second listen," he tells me. At the 11th second, however, music industry demographics kick in -- and Jean's audience remains hard to classify. "People will be like 'I don't know what's going on with you, because I like you, my mom likes you, and my little brother likes you,'" Jean explains. Six-year-old children and 60-year-old women line up for his shows; truckers have stopped him on the road, he says, to confess that he's their favorite artist.

Jean told me he is in the midst of churning out a French Creole album, a reggae album (à la Gregory Isaacs) and a hip-hop album, "Silent but Deadly" (whose first single is "If I Was President"). He's cultivating talent for his own Clef Records: 18-year-old Trini Don, who's been described as a female Notorious B.I.G., and 3 On 3, singing brothers from the Bronx who happen to be sons of former Harlem Globetrotter Muggsy Bogues.

Platinum Sounds is a Wyclef Jean album come to life: You never know who'll turn up. Among those who did while I was there: the manager of politically radical, indie rap duo Dead Prez; a posse of men in jackets splashed with "Bad Boy," for P-Diddy's un-political, un-indie label; a P.R. rep for reggae label VP Records; bearer of the tentative treatment for Jean's new video, to be shot in Miami's Little Haiti. Following the crisis in Haiti, one video became two: Jean returned there to make a statement about Caribbean unity, shooting a second, as yet unreleased video, featuring American rapper Scarface, Jamaican reggae artist Buju Banton and Haitian group T-Vice.

Don't call Jean a rapper. "I'm a hip-hop musician," he says, seated comfortably on a black leather sofa and surrounded by guitars, which he's adept at playing. "I want to make healing street music. To address the things that matter -- you know, life, love," he explains. "To say something. Of course, keeping it sexy, because I'm very sexy. But food for thought. Like a good book." He calls "The Preacher's Son" his most recent "good book." It's a label I endorse: "The Preacher's Son," while released to minimal fanfare, is addictive. It has requisite radio bangers ("Party to Damascus," with Missy Elliott) and duds ("Industry," a plodding journey through hip-hop blunders). But on "The Preacher's Son," Jean does more singing than rapping. This is good, because Jean is a "rapper" only in the strict sense of the word: He chats over beats and music. He lacks varied intonation or rhythmic flow, which is what rapping is really about.

His singing, though, is bad. I mean bad bad, but now that falsetto-fixated rappers who can't sing -- like Andre 3000 or Pharell Williams -- are a hot commodity, bad bad is good bad. Jean can carry a tune but barely a note. So when he sings, he sounds as if he's half joking; you're never sure if he's serious about his voice or being ironic with it. And in the end it doesn't matter, because the effect is compelling. Pair Jean up with a woman whose singing is good good, and the effect is mesmerizing. He and Lauryn Hill discovered that formula in the '90s, but since the Fugees disbanded, Jean has tapped it for a string of collaborations with ur-Lauryns -- his best one is "911," with Mary J. Blige. Jean has described the song as "one of those things that god put together," and it's that rare Wyclef Jean hyperbole that isn't, in my mind, hyperbole.

Jerry "Wonder" Duplessis, Jean's longtime producing partner, arrives at the studio and dispenses with his black leather jacket. Wonder is Jean's first cousin, and Jean -- who really is, by the way, a preacher's son, and really named Wyclef Jean (first name: Nelust) -- has long kept his music in the family. At age 9 Jean moved from Haiti to Brooklyn's Marlborough projects, and then to Newark, where he played guitar in a church band that also included his two sisters and two brothers -- "the Beatles of the church," he calls them. His parents kept close watch on what emerged from their son's radio: Christian rock and country music were acceptable, as was secular music with a philosophical bent. The two Bobs -- Dylan and Marley -- thus made the cut. And Jean has been compared to both: Howard Dean called him "the Bob Dylan of the hip-hop generation," while Jean himself told me that in Haiti, he might as well be Bob Marley himself. As if to fit that bill, Jean's music has, in content and delivery, grown more and more Marley-esque. On "The Preacher's Son," he has a song titled "Rebel Music" and one in which he and Buju Banton seem contenders for the "modern-day Marley" crown.

"Hip-hop today needs the spiritual tone of reggae," Jean says, launching into a jeremiad that befits a preacher's son. "Hip-hop used to be, 'I feel like listening to some conscious music -- so throw on a De La Soul record.' And then, 'I feel like laughing -- throw on "Parents Just Don't Understand." I feel like getting on some gully, gangster vibe -- throw on Kool G Rap. Some universal hip-hop? Run DMC.'" Now, he continues, hip-hop is limited to one subject. Or three: "Cars. Jewelry. Women. Period." He's certainly not immune -- two and a half years ago he began hosting a car show, showcasing his collection of 37 exotic cars.

His gripes would be tedious and trite -- mourning the music of yesteryear has long been a hip-hop sport -- if not for the fact that when it comes to the younger generation, Jean puts his money where his mouth is. To aid children in the U.S. and Haiti, he founded the Wyclef Jean Foundation. He was arrested for protesting New York City's 2002 education budget cuts. He's held countless benefit shows for a slew of charities and recorded social justice songs like "Diallo." He recently told New York Newsday that his new single is inspired by one wish: "I want to help educate [youth] about how important it is to vote."

But attend one of Jean's shows -- as I did in New York, well before our meeting -- and the stale phrase "conscious rapper," which connotes backpacks and soapboxes, never comes to mind. Jean put on a musical revue that merged inspiration and education. He spent most of his stage time ensuring that the under-21 crowd knew music wasn't born yesterday, nor is it solely an American occupation. He rapped a verse or two, then danced salsa to a Celia Cruz tune. He played a decent-sounding riff on his guitar and reminded everyone that African-Americans were rock 'n' roll originators. He shared the stage with sundry guests: reggae artists, gospel singers, b-boy dancers. And throughout, he hopped about the stage gleefully, dreadlocks trailing behind him, as if possessed by the music -- as if to say, "I'm having fun!"

Gearing up to make music, Jean is having fun in the studio today. A batch of men from Guadeloupe have materialized, and one of them is Admiral T: a slender fellow who looks about 19 and is, I'm told, is a reggae star in the French-speaking Caribbean. He's here to record a track with Jean, whose fist he pounds diffidently.

Dispensing with formalities, Jean is soon joking with the men in Creole-tinged English. He bounds toward the stereo and slips in Admiral T's album. As Jean plays and replays Admiral T's French reggae tracks -- "Pull up!" he cries, which is reggae-speak for "that song is so good, we must rewind it!" -- I try to reconcile the reticent young man in front of me with the commanding voice blaring forth from the bass-heavy speakers.

Sufficiently warmed up, Wonder, Jean and Admiral T turn their attention to the task at hand. Wonder cues up a beat; Jean and Admiral T begin formulating lyrics for a verse that's a paean to Caribbean women. It'll be delivered in French Creole, but Jean scribbles lyrics in English and, aided by his French-speaking set, translates.

"My girl from Martinique -- let's see ... she's what?" asks Jean, to no one in particular. "What are Martinique women known for?" Admiral T is stumped; they skip that one and move on to Jamaican women, then Trinidadian ones.

"My ghetto girl!" exclaims Jean, relishing the phrase. "My ghetto girl -- I need a good line for her! Like: 'My ghetto girl will always hide my pistol.'" He laughs heartily. (Jean says his wife, Marie Claudinette Jean, is a "'hood kinda girl," though she's also a designer of her own couture clothing line, Fusha. The pair have dated since childhood and they still live, sans children, in New Jersey.)

"I need to come up with a really good one for the ghetto girl," says Jean. Instead, he races into another room and returns with a small keyboard, which he begins tinkering with. Intrigued by the sound of his notes, Jean hooks the keyboard up to a mic so he can add them to Wonder's beat. Twenty minutes later he's back with a guitar. Half an hour later he's back with menus from a nearby Caribbean restaurant, instructing his assistant to take our dinner orders. Evidently no one is leaving this studio anytime soon.

By the time I do leave, well into the night, Jean hasn't eaten his dinner yet. He hasn't stopped playing with his studio toys, either. Poised at the mic, he's merrily delivering lyrics and, obviously, just getting revved up. His collaboration with Admiral T is shaping into a relentlessly energetic track with a hip-hop beat and a world-beat soul.

When I asked Jean where he sees himself in 20 years, he answered me without flinching. There was no talk of a Fugees reunion -- although he says he's not opposed to one. ("The world needs another Fugees record," he'd told me, adding that such a record would sell "like Michael Jackson numbers, like 'Thriller' numbers.") There was no talk of a forthcoming clothing line, a high-profile retirement, or a lucrative career playing a thug in Hollywood productions -- which makes him one of the only hip-hop stars in existence not banking on one or more of the above.

"I'm just a music man," is what he told me. "I don't see myself without a guitar in my hand, playing for a crowd."

Playing for a crowd, indeed. If one spirit reigns in the world of Platinum Sounds -- which is the world of Wyclef Jean -- it's the spirit of play. And that, I realize, is why rumors of Jean's greatness are not overrated. Artistically inconsistent as he is, Jean is one of the few left in hip-hop who are in it for one reason: the love of music. He has fun listening to it, making it, collaborating on it, experimenting with it -- even if he's alternately failing miserably and innovating brilliantly. Being "just a music man" is no small feat in a music industry that more and more resembles a corporate ladder. As he dances his way from one room to another -- here perfecting the bass on Wonder's beat, there chanting lyrics, slightly off key -- Jean seems content to remain on his rung, as long as he can make merry, meaningful music there.

Shares