To those of us who believe that Marlon Brando is the greatest American actor we have ever seen or ever will see, his death yesterday at 80 calls up a kind of bewildering doubt. "I expected him to live forever," said the friend who called with the news. When someone whom you expected to live forever dies, it can seem easier to wonder if he ever existed than to try to imagine the world without him.

The cynical reply to that would be that Brando long ago stopped being a vital force in American acting; that (as he admitted) his movie appearances of recent years were made mostly for money; and that, with the exception of "The Freshman," a sweet, screwball burlesque of his role in "The Godfather," the movies themselves were a forgettable lot. They were: "A Dry White Season," "The Island of Dr. Moreau," "The Score." In the last one, Brando reportedly clashed with the director, Frank Oz, who would not allow Brando to be as flamboyant as he wished in the role of a foppish gay crook. That might be a summation of the mediocrity that has stymied every original who has ever worked in American movies. For where, in the natural order of things, can you imagine Marlon Brando being impeded by a pisher like Frank Oz?

Yet there wasn't one time Brando ventured onto the screen in the last two decades when, his infamous public protestations about the indignity of his profession aside, he didn't show off wit and juice and a sly joy in acting. Just watch his scenes as the anti-apartheid lawyer in "A Dry White Season." He's playing a man who knows he will never prevail against the crooked South African courts but who takes a sort of delight in the performance opportunities that a court case gives him. The lawyer knows that just doing his job as well as he can makes everyone around him look corrupt and foolish. That was often Brando's effect in the movies he appeared in.

Brando could even make good actors seem stodgy. He does it to that fine actress Teresa Wright in his 1950 debut "The Men." Brando plays a paraplegic World War II veteran and Wright the wife he can barely face after the humiliation of being unable to make love to her on their wedding night. It's a situation that Hollywood might have handled before in the discreet, conventional terms of the "well-made" social-problem picture (the specialty of the film's producer, soon to become execrable director, Stanley Kramer), and for most of the movie it does. But Brando's restlessness, his impolite directness, the sense of frustrated motion he implies often with just the ejaculations and guttural breaks of his speech patterns, make it impossible for us to think we're simply watching a fine young man sitting down. In his first movie, Brando refused the easy sympathy that a young actor playing a wheelchair-bound vet could have milked. He's sympathetic but not always likable, and his self-pity is of the raging, festering variety. Everything comes together in the movie's most explosive moment: Brando in a bar encountering a guy blathering on to him about the great sacrifice he's made for his country. "God bless you, mister," Brando says. "Can I marry your daughter?" He uses the question like a knife that he turns on everybody -- that man, his daughter and himself.

The change that Brando's acting in "The Men" represented got its fullest expression in his two best collaborations with Elia Kazan, "A Streetcar Named Desire" (Brando had originated the role of Stanley Kowalski on Broadway) and "On the Waterfront." The roles have become so familiar, so parodied (even Bullwinkle bellowed "Stelll-la!!!"), so honored (i.e., taken for granted) as a part of our cultural heritage, just as Brando's performance in "The Godfather" would be nearly 20 years later, that you need to go back to them to remind yourself how fresh they still feel. And not just in the moments everyone remembers -- "I coulda been a contender" or "We got here in the state of Louisiana what's known as Napoleonic code" -- but in the offhand moments, like Brando's absentmindedly trying on the glove that Eva Marie Saint drops in "Waterfront."

You can trace almost all the greatest American screen acting since then to Brando: Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Nick Nolte, Ed Harris, Debra Winger, Jessica Lange, Sean Penn, Nicolas Cage, Robert Downey Jr., just as you can see parts of his lineage in the work of James Cagney and Barbara Stanwyck.

It's a lineage and a legacy explored better than anywhere else in the critic Steve Vineberg's 1991 book "Method Actors." And yet it's a lineage that remains largely misunderstood. Brace yourself, in the days ahead, for obits talking about Brando's mumbling or parroting the idea that Method acting is about "becoming the character." Vineberg's argument was that the main aim of the Method -- psychological and physical verisimilitude -- coincided with the realism and naturalism that has been the primary style of American moviemaking and playwriting, and of American life. In other words, the Method fit our native casualness. It suited our actors because it allowed them to go from point A to point B with the least possible fuss. And, because it put a premium on emotion, allowed them to travel that route as deeply as possible.

Maybe it's the fate of every great original to have his or her career and art misinterpreted or tidied away in the most trite, convenient summations. It seems that Brando's career was more susceptible to that than most. His performance as Don Vito Corleone in "The Godfather" was heralded as a comeback even though he'd never stopped doing great work. ("Is Brando marvelous?" Pauline Kael asked in her review, and answered, "Yes, he is, but then he often is.") Of course there were stinkers. But you can't find an actor working in Hollywood during the decline of the studio system who doesn't have at least as checkered a résumé. (Everyone remembers Paul Newman in "The Hustler" or "Cool Hand Luke," but nobody talks about "The Secret War of Harry Frigg" or "What a Way to Go!")

Brando had gone daringly far as the repressed homosexual Army major in John Huston's underrated 1967 film of Carson McCullers' "Reflections in a Golden Eye." Just as he had in "The Men," he made you uncomfortably aware of this preening, closeted man's physicality; he made you feel the suffocation of his repressed desire. And in the only film he ever directed, the 1961 western "One-Eyed Jacks" (which he took over after Stanley Kubrick dropped out), Brando predated the sacrificial hipster rebel hero that would flower in pictures like "Easy Rider" and "Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid." And he did it without all the sickly Christ pathos those movies wallowed in. The picture is terrific, and Brando is dangerously sexy and funny in it -- especially the moment when he stands over a man he's knocked down in a bar and seethes, in that purring, sibilant voice of his, "Get up, you big tub of guts."

Part of the greatness of Brando's acting was that it never lost a sense of play. One of the best moments in "The Godfather" comes when he is declining an invitation from Al Lettieri's Sollozzo to join him in the narcotics-distribution business and Brando offhandedly brushes some lint from Lettieri's suit. It's the most subtle and devastating put-down you've ever seen, an adult putting in place a kid who has impertinently and prematurely put on his first pair of long trousers.

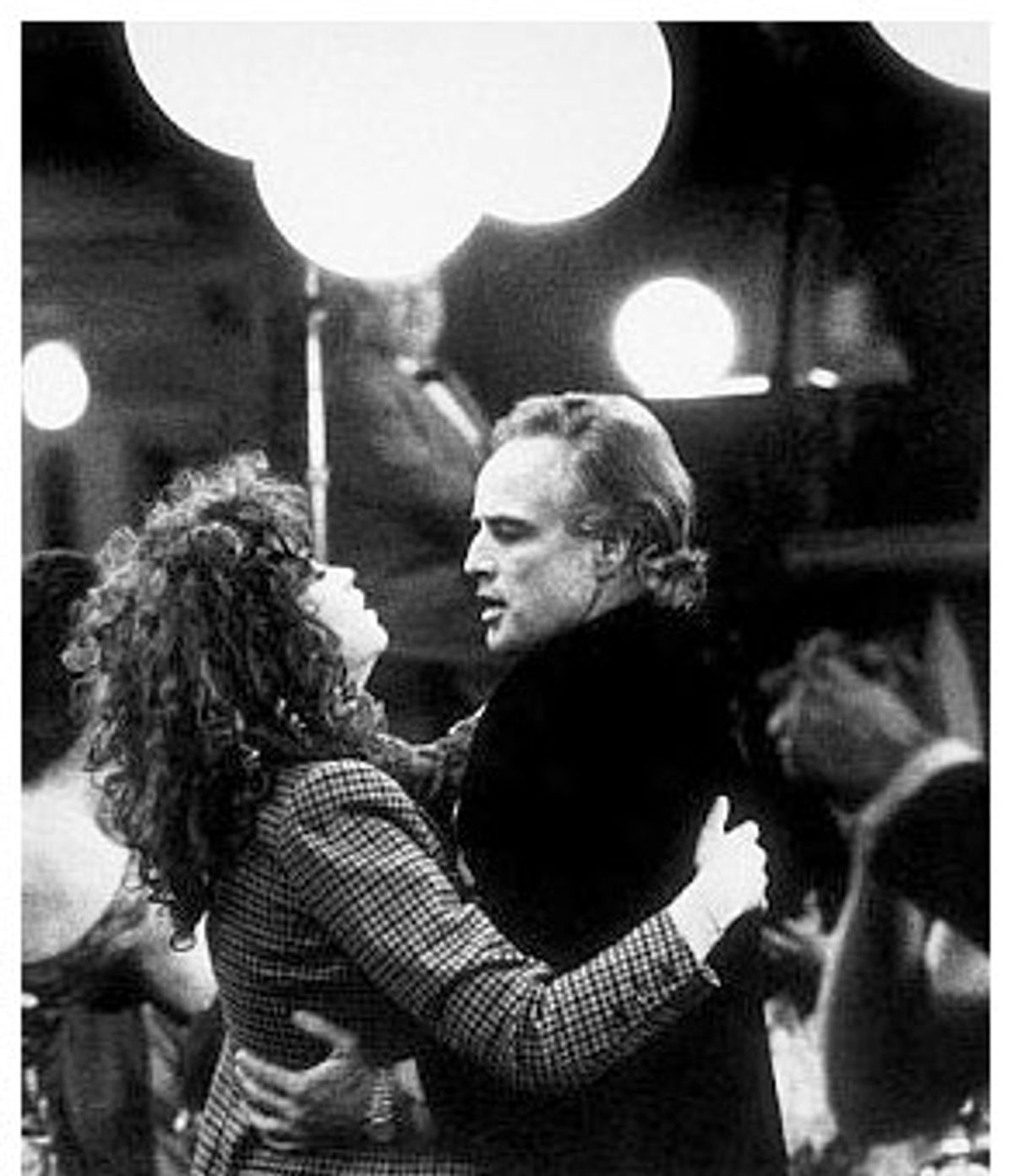

That playfulness is why Brando was a natural in comedy, why his performance in the wonderful "The Freshman" is one unbroken delight. Here Brando took his revenge on every second-rate nightclub comic who'd ever done a Don Corleone imitation. He took everything that had been exaggerated about the earlier performance and went even further with the exaggeration. The loveliest moment comes in a shot of Brando ice dancing with a young woman to the tune of Tony Bennett singing "I Wanna Be Around," the perfect emblem of the light, graceful touch he shows throughout the picture.

For me, though, it's Brando's performance in Bernardo Bertolucci's 1972 "Last Tango in Paris" that remains not just his greatest but the greatest performance I've ever seen an actor give. It's fashionable now to put down "Last Tango" as a movie that's no longer as "shocking" as it once was. But it was fashionable to put it down when it came out in America in the heyday of porno chic. And though I usually detest this form of argument, in the case of "Last Tango in Paris" I have to say that I have never heard one argument made against it that didn't sound like fear of facing up to its power.

The true nakedness in "Last Tango" isn't the nakedness of Brando and Maria Schneider's bodies but the nakedness of their emotions. Despite the periodic landmarks -- "Pandora's Box" in the '20s, "Last Tango" in the '70s, Catherine Breillat's "Romance" in the '90s -- the movies have been the most timid of the arts in exploring the erotic. Or perhaps it's more accurate to say that movies have continued to kid themselves -- and the audience -- that the erotic is the only impulse at play in sex. "Last Tango" turned Freud on his head. It was not, Bertolucci was saying, that everything came down to sex, but that sex came down to everything else.

Brando brought the rage and bitterness and disappointments of middle age into sex. He showed how even the gambit of reducing sex to purely physical instinct wouldn't keep the demons at bay. Pauline Kael's famous review talked about how for older audiences the movie was like seeing pieces of your life; for younger audiences, it was potentially upsetting -- they would not want to think that anything like that awaited them. And yet what Brando achieves in "Last Tango" is so much richer, so much more profound than the "truth-telling" that has often passed for acting and filmmaking (as in the work of John Cassavetes).

His great achievement in "Last Tango" wasn't just the fearlessness of the performance but the way the performance is the most realized example of the Method ideal -- crafted but not shellacked; rooted in exploration but not faltering; incorporating pieces of the actor's personality but as an expression of the character he is playing. It's a performance that matches the ravaged repose we see in the Francis Bacon portrait that accompanies the film's opening credits. When Brando delivers a long, mournful reminiscence of being forced to milk a cow in his best shoes and then going to pick up a date with the stink of cowflop filling his truck, it's clear he's drawing on his Nebraska boyhood, just as the character's résumé of jobs echoes roles Brando has played in the past. In a lesser actor, what's being expressed in this performance -- sourness, rage, the romantic's compulsion to play the cynic in order to reduce everything to its basest motives -- could have seemed ugly, self-pitying, certainly without the battered lyricism Brando gives it here.

There is so much more to remember Brando by than "Last Tango in Paris," but there's no diminishing the performance. When the film came out, Robert Altman said, after seeing it, he felt Bertolucci attained such a level of honesty that it left him feeling he didn't have the right to make another movie. Brando's performance can make you feel the same thing about acting -- if an actor isn't going to aspire to this level of instinct and craft, this willingness not to hide, then what's the point?

Shares