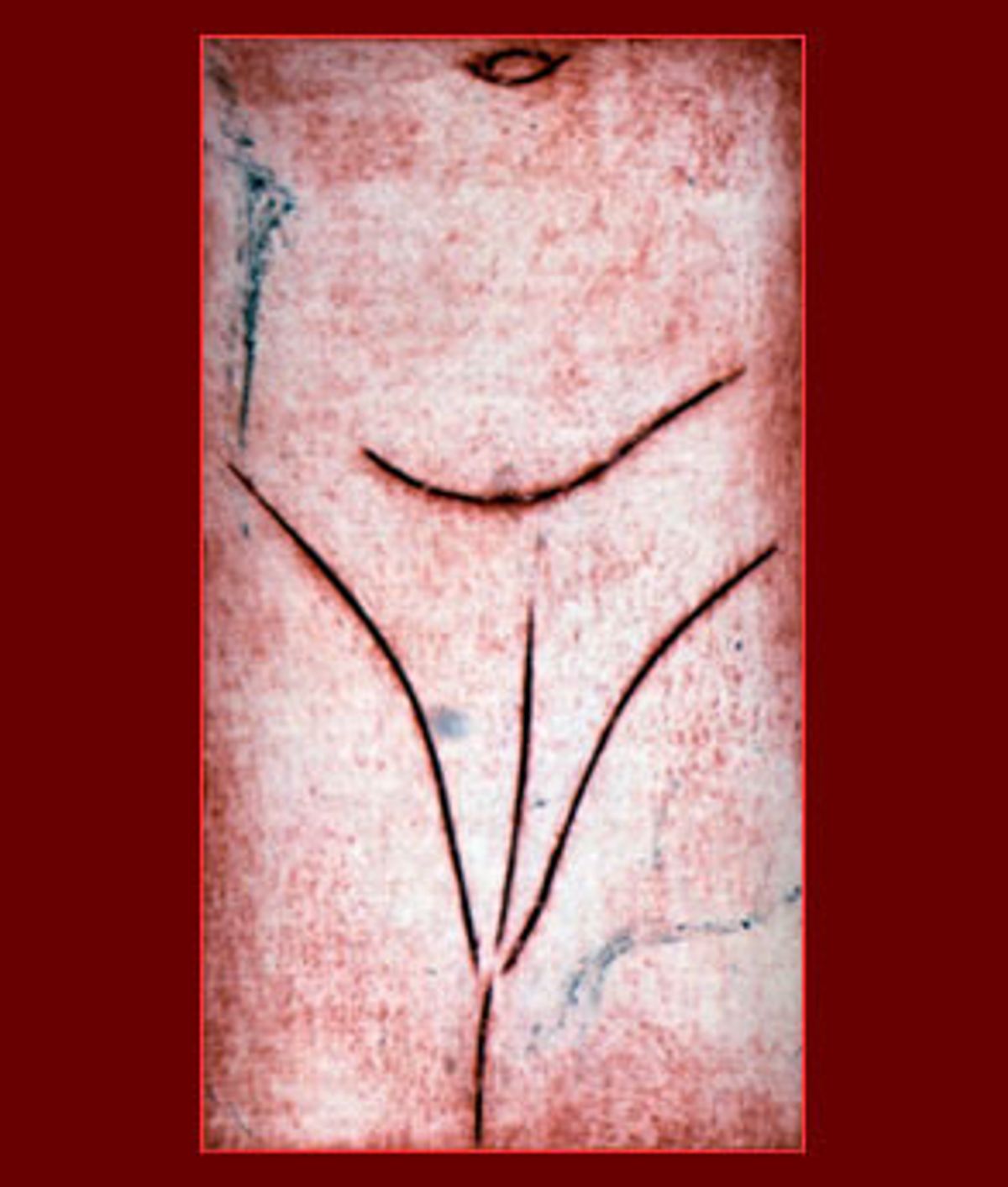

"Why not put genitals where our eyes are and our eyes between our legs?" Picasso once asked. It was a rhetorical question for a painter whose work was driven at times by an almost fetishistic interest in sex. Flesh, folds, phalluses, slits, holes (and what the surrealists called "the toothed vagina") -- Picasso painted a voluptuous, tumescent world of opposing forces and forms, a ribald pleasure palace of the senses. The "Erotic Picasso" exhibition currently at the Jeu de Paume in Paris is the first show ever dedicated to the master's libidinal soul.

The more than 300 works in the show map the erotic landscapes that made up Picasso's world, and half of them have never before been publicly shown. (They come from private collections.) Largely inspired by the bordello, the young Picasso sucked on the teat of his own sexual imagination and, one assumes, interests. More than just garden-variety sex is depicted here. There are orgies, oral sex, masturbation and lesbian love. The works are at once obscene and tender, vulnerable and bawdy. Not only is the sex heterosexual and homosexual, in some cases it's zoomorphic.

The naturalism in Picasso's early work quickly gave way to an extraordinarily diverse range of erotic symbolism. Bulls and centaurs came on the scene, along with his trademark polymorphously sexual Minotaur. The dualities of love and death loomed large on his canvas with the advance of age, as did a consistent theatrical strain of voyeurism, which reached an apex when Picasso was well into his 80s.

Sadly, this vast exhibition has been ignored by the American curatorial world, suggesting to its curator and others a certain consensual Puritanism about the role of public art. Says art historian Jean Clair, "You have to be American to believe that art must educate children and purify adults, that it is necessary for the welfare of an enlightened society ... the artist is a criminal, an outlaw, a pervert." Picasso put it differently. "Art is not chaste," he once said. "Yes, art is dangerous. If it is chaste, it is not art."

To get the inside out on priapic Picasso, Salon spoke recently with Gérard Régnier, director of the Picasso Museum in Paris and curator of "Erotic Picasso."

How did the exhibition come to pass?

There's nothing original in the idea. I think everyone has always wanted to do an exhibition on erotic Picasso. All of Picasso's oeuvre is erotic, the most erotic that exists in the world. Doing a show on this subject is compelling, interesting and most exciting, in every sense of the word. When I became the director of the museum I realized that there had never been a show on the erotic Picasso. It was a totally virgin subject, so to speak.

And why?

It's interesting. Maybe a sociologist could understand why. Perhaps for two reasons. First, in the austere and serious museum world, approaching art through the angle of eroticism is always a bit provocative. You have to find accomplices to do this. You have to find a team with whom you share a certain spiritual complicity for the subject. And that's not always easy to find. I found that [accomplice] when Jean-Jacques Lebel (a French artist and culture maven) came to me and asked, "Why not?" I replied, "OK. Let's do it."

And there's another deeper reason for this. The history of art, particularly of modern art, has always been controlled by a formalist approach and not an existential or erotic approach. We're more interested in little squares than we are in meaning, in particular in Picasso's case. We've been hypnotized and fascinated by his little squares -- the cubism -- without realizing that essentially all of Picasso's work is about curves. If you look at Picasso's work in its totality, he spent his life drawing voluptuous curves and very little time making squares. In fact, Picasso's cubist period was very, very brief.

The French speak about a certain moral terrorism in the U.S. What was the reaction in the American art community to the exhibition?

There's an enormous cultural and intellectual difference between the U.S. and Europe. I say that in all friendliness. I've lived in the U.S. and studied at Harvard; I know the country well. But the fact remains that our exhibition has been requested by six important museums around the world, and not one of them is American.

Do you attribute that to the same old American Puritanism?

There's certainly a puritanical context that prevents an important exhibition like ours from being seen in New York or, let's say, Texas [laughs], or in other American cities. In Europe, Madrid wants the exhibition, Valencia wants it, Munich wants it, Rome wants it.

Did you have any feedback from your American counterparts? Any comments at all from, say, the people at the Guggenheim or the Museum of Modern Art?

No feedback. No feedback whatsoever. And I'm in contact with them every day. [Both New York MOMA director Kirk Varnedoe and San Francisco MOMA director David Ross told Salon that they weren't offered the show.]

That's remarkable!

Indeed. There's another reason besides Puritanism. There's a certain moral reflex that has to do with the formalist tradition in America. For Americans the historical tradition that is associated with Picasso is cubism, the decomposition of the object through the cubist perspective, and it's not at all about eroticism and related iconography. So we're in an entirely different perspective here. It shocks Americans. It's very interesting that the only hostile piece in the press was published in the American press. [In a short review Time magazine called the show a "ragbag" that "falls victim to the same law of diminishing returns as a dirty movie."]

The Time article suggests that there's still a politically correct context with respect to sexuality in America. The reaction of the Time journalist reflects other things as well -- for example, the fact that books published on Picasso's life in the States invariably represent him as a sort of male chauvinist pig who didn't love women. It's interesting that this misconception persists in America. There's tremendous freedom in America, but also tremendous rigidity and closed-mindedness, particularly in the intellectual realm.

When I put together the Vienna exhibition at Beaubourg in 1985-86, I showed work of [Gustav] Klimt and [Egon] Schiele that was openly erotic. When MOMA took the exhibition, it became -- how shall I say? -- very clean.

You mean they removed certain paintings that were erotic?

Of course. And the show became soft, mild, polished.

Lebel has said that it is always the essential that is censored. Do you agree?

That's true, yes.

How would you situate Picasso's work in his own time? Was his erotic work considered shocking back then?

I don't think so. In fact in every era artists create a tremendous amount of erotic work. [Jean Baptiste Camille] Corot, who was so sweet and kind and mild, produced erotic work that would shock people if they knew about it. The same is doubly true with respect to [Gustave] Courbet. And [Eugène] Delacroix -- don't get me started. All great painters have produced erotic work because it is -- how do I say it? -- making objects with clay is in and of itself a very erotic act.

In other words, there is something essential here, even primal on some level?

In the Lascaux caves in France, in the deepest, most inaccessible and least visible part of the caves (which proves that sex has always been taboo and sacred), you have the first figurative representations, which date back to around 20,000 B.C. There's an image of a man lying down with a lance. Next to him is a bull with his guts exposed, who was probably killed by the man. And the man was probably killed by the bull. The man is dead, lying down, with an erection. This was the expression by cavemen of a fascination with sexual strength, the strength of life.

How would you define the difference between eroticism and sex?

I think that etymologically sex has to do with the fact that men and women are not the same. Sex is about division, separation. It's a biological fact, physiological. It's true that today everyone, everywhere, talks about sex, sex for its zoological nudity, so to speak. And that creates a certain permissiveness that manifests in, say, the explosion of pornography, the X-rated, after-midnight culture. Sex is everywhere. There's a sex invasion. If you talk about eroticism, you're talking about a cultural tradition that is related to antiquity, to the god Eros -- and a cultural practice that has been refined into a sort of etiquette code for men and women.

How much of Picasso's work is about imagination and how much is personal anecdote?

Picasso was actually a very modest and chaste person. His erotic iconography is rarely blatant, crude, immediate. There's always a disguise of sorts, via mythology, for example, and fable. It's rarely just a man and a woman making love. It's usually a god or a goddess.

Or a Minotaur.

Yes, the Minotaur is one of the acceptable mythological forms that Picasso used like a costume. But the Minotaur is ambiguous. Sometimes he's aggressive, but he's also tender, he's also the victim.

That being said, there is a fair amount of explicit sexual representation in his work.

Most of it was done when he was a teenager.

One has the impression that as he aged, the expression of his erotic self became more complex, more voyeuristic.

There is more complexity as he aged, as coitus became more problematic. But that was during the last years of his life, when he was in his 80s.

This is not an exhibition likely to be seen again, since so much of it is from private collections.

Who knows? Maybe it will set a trend in the United States. [Laughs] In any case, when people leave the Jeu de Paume they are happy, lively. There's nothing unhealthy, scabrous or disgusting in the show. It's so strong, so full of life.

What do you think Picasso would have said to the idea of an "Erotic Picasso" show?

I think he would have said, "Why not?"

Shares