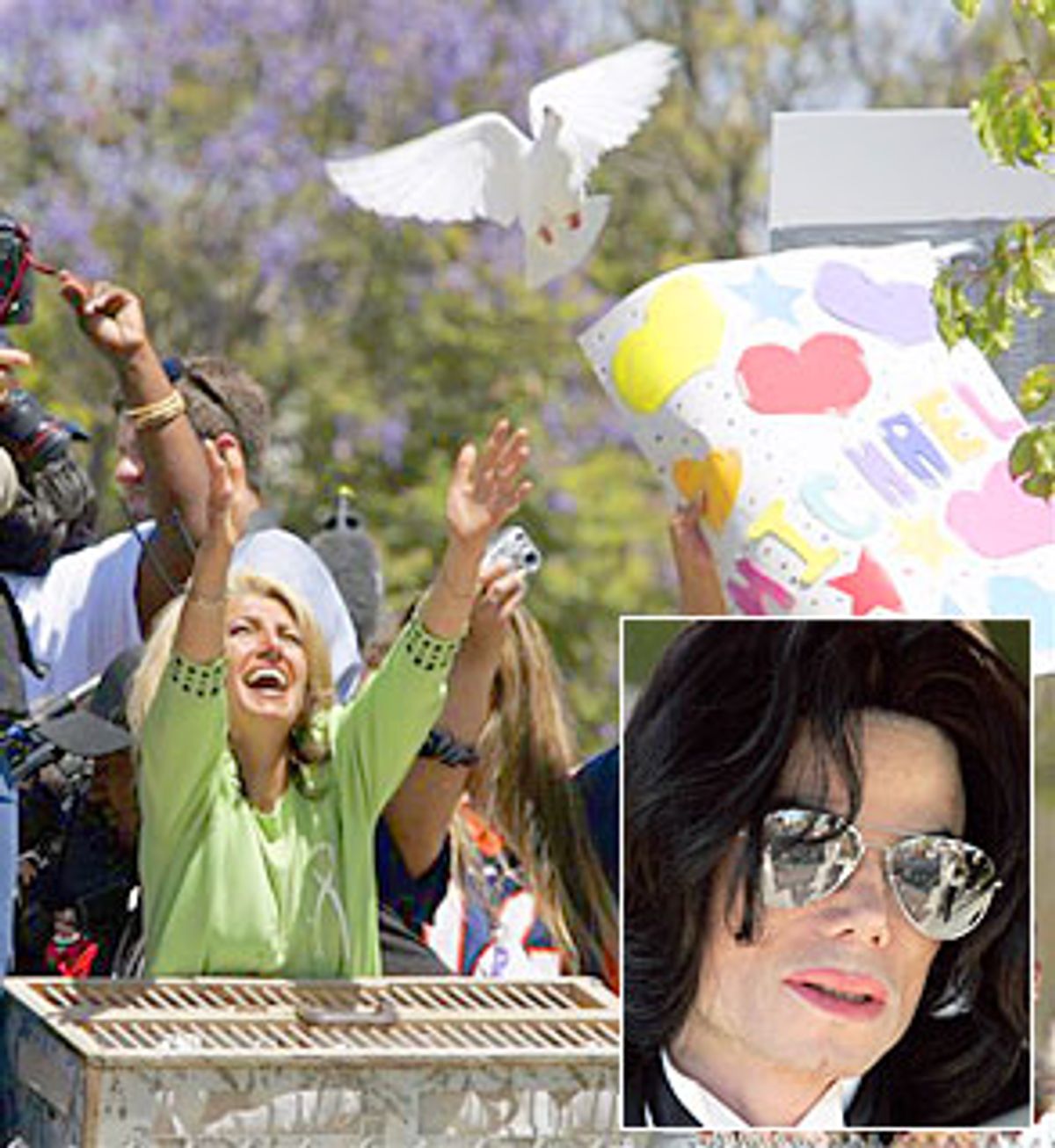

It's over. Michael steps out into the sun, the doves are released, the already overcrowded Santa Barbara jail won't have to make room for a very special guest.

One more time, a celebrity beats the rap. It should give Martha Stewart something to think about that she's the only megastar who couldn't. And yet, one more time the show ended with the sense that the truth remains somewhere "out there," shadowy and elusive. One more time, it's hard to discern any moral of the story.

The Michael Jackson trial was part of an epic cycle of celebrity trials that started with O.J. Simpson, passing through Kobe Bryant, Robert Blake and Phil Spector (Tyson and the Menendez brothers also bear mention). These trials -- sometimes televised, other times reenacted, always dissected and second-guessed with obsessive attention -- have undoubtedly become a new genre of entertainment. They are American tragedies for our age -- big, crass, bizarre and, most crucially, morally empty.

The crimes or alleged crimes involved are as serious as they could be: murders, rape, pedophilia. The suffering, or alleged suffering, is profound. The scope and impact of the trials -- from the investigations to the legal strategies, the media spin, the social repercussions -- are huge. Yet it's impossible to wrestle from them the moral or even the psychological lessons that classic tragedy provides.

Celebrity trials offer a potent cocktail of fame, sex and violence; they allow us to look behind the veil that usually protects the private lives of stars; they tap in to collective feelings and fantasies about the very nature of celebrity. What they don't do is provide solutions, or even serviceable frameworks, for questions of right and wrong. Ultimately, they are just not about right and wrong. They are about wrong and wrong, and though they are tragedies inasmuch as they deal with terrible deeds and their retribution, they suggest a new definition of tragedy.

In the common use of the word, tragedy can happen when "right" clashes with "wrong" and succumbs to it -- taking the form of sacrifice -- or simply when somebody's "innocence" meets somebody else's guilt -- taking the form of "victimhood."

But classic tragedy is more complex; it has been defined as the deadly clash of "right and right." In "Antigone," the protagonist dies in the name of a simple principle: a sister must give her brother a decent burial. King Creon had forbidden the burial in the interest of the kingdom and must now -- despite himself -- carry out the consequences of his order, which is law, being disobeyed. Fraternal love clashes with the law: Both are right in their own way, but the two rights are irreconcilable. We watch the characters pay the price of their acts, and so fulfill their destiny, in a clean, inexorable, hopeless drama. The truths we learn are certainly bleak and sobering, but they also illuminate the supreme value of courage, coherence, compassion and knowledge itself.

Finally, in a more banal sense, tragedy can happen when random circumstances produce terrible outcomes, as in any "tragic accident."

American tragedy, as embodied in this cycle of celebrity trials, seems to present something different: the clash of two people -- or two "forces" -- who are both in their own way wrong. O.J. and the LAPD. Robert Blake and his wedded grifter. Kobe and his testimony-shifting accuser. Michael Jackson and his alleged victim's mother-pimp. (The exception here is Phil Spector, who allegedly took the life of a waitress-actress whose only mistake was to accept his invitation.)

We (a lot of us, anyway) follow and discuss these trials to establish degrees of wrongness, or simply to see which wrong will carry the day. Few people would argue that Michael Jackson didn't cross a line with his bed sharing; the question was only how far he went beyond it. But at the same time, few people would argue that greed and hypocrisy didn't taint the accusations against him; the question was simply whether we could still buy them at all. When presented with this kind of situation, we must choose, or accept to be divided, between two wrongs. We don't have to believe that anybody is telling the truth. We can believe both that O.J. did it and that the LAPD is (or was) crowded with racists who compromised its credibility. That Robert Blake did it and that Bonny conned him six ways to Sunday. That Kobe did it -- that he did "something" -- and that his accuser set him up and embellished the tale. If there are innocent victims, they appear to be "caught in the middle," or twice exploited.

The outcomes, therefore, cannot be "resolutions." There is no "moral of the story" -- if not a twisted, ambiguous, ironic one. O.J. gets off as a slap in the face of the LAPD; he becomes persona non grata in his former L.A. hangouts and has to relocate to Miami. Kobe gets off but has to admit infidelity and make it up with gifts of oversize jewelry, tattoos honoring his "queen," and renewed commitment to his fans (as ultimate proof of his new faithfulness, he re-signs with the Lakers). Michael Jackson gets off but may soon have to sell the Beatles catalog back to Sony.

Much as classic tragedy is exact and rigorous, this American tragedy is messy and arbitrary. It is tragedy crossed with melodrama in its most degraded expression (the soap opera). It is tragedy for people who crave the frisson of morbidity much more than any catharsis. Classic tragedy is hopeless because the tragedy is preannounced and inevitable. American tragedy is hopeless because it assumes that we all are. One type of tragedy is moral; the other is cynical. We hear the rhetoric of the lawyers knowing that it's just that -- rhetoric -- and knowing that everybody knows it. When both parties are somehow guilty, not only innocence but truth itself becomes "impossible." Any truth will always be subjective, muddy and ultimately unsatisfying, like a negotiated, artfully worded statement. The truth is then beside the point: the point is just to win, to put one over the other guy. In classic tragedy, everything is known, everything is understood in its very terribleness. In this form of American tragedy everything is ultimately unknowable and impossible to understand.

But then, why do we need it? Why do we turn these trials into such compelling spectacle?

The answer, I think, has two levels.

First, the trials reveal that our relationship with celebrity has become perverse. As a spectacle, they are of a piece with VH1's "Behind the Music" and the E! Channel's "True Hollywood Stories": mostly tales of excess and decline that satisfy people's appetite for the sorrows of the rich and famous.

This appetite, which has always been the inseparable underside of the adoration for stars, seems now to be out of control. We are now likely to feel stronger about the celebrities we don't like than the ones we like: a "reverse fandom" that can be a form of satire but easily spills into meanness. If we don't like certain celebrities, we want to see them embarrassed, ridiculed, reviled. If we like them, we still want to see them exposed at their most vulnerable. More interesting than the work celebrities do is the work they have done on them. We obsess on the weight they gain or abruptly shed, the fashion blunders, the mating patterns, the abrupt weddings and divorces. The union of two celebrities seems to create grotesque two-headed monsters such as "Bennifer" or "Brangelina."

At the beginning of jury deliberations on the Jackson trial, the New York Post ran a front-page headline screaming: "Sweat, Freak." It made me feel sorry for Michael Jackson, but I'm sure the folks at the Post knew what they were doing. The growing industry of tabloid journalism seems to thrive on feelings of resentment and hate. And while those feelings may not have been shared by the Michael Jackson jury (or perhaps that jury disliked the accusers more), it's unlikely that the acquittal will win Jackson any new fans.

Hypothetically, there is a version of celebrity trials that would be akin to classic tragedy: that is, a clash of right and right. The idea that all should be equal in front of the law, and the idea that celebrities are "special" and may need an extra measure of protection, are arguably both right. But the second idea becomes a compelling principle only when the special status has to do with merit. And here is the rub. Celebrity has become less and less meritocratic. We used to have Angelyne, whose self-conferred celebrity was always a fairly innocuous joke. She acted as if she was entitled to our attention, but she got it only for the time it took to drive by a billboard. But now we have Paris, who acts in similar way but gets a TV show and the big bucks. And if indeed we'll always have Paris, we'll also have this giant backlash against celebrity. It's as if celebrity itself is the product of two "wrongs" -- the corporate marketing of inflated egos, and the public's lack of taste. The public may buy it, but it will feed their general sense that celebrity is undeserved. One may become a singing star boosting his or her voice with technology and shaking ass in the video. Or a movie star with the help of plastic surgery. Or a sports star with steroid-powered muscles. The more people are led to believe this, the more unhealthy their relationship with celebrity will get.

The second level of the answer has to do with power. Truly powerful people (politicians, moguls, industry titans) are themselves a kind of celebrities, but traditional celebrities are sort of the "face" of power and become our stand-ins for it. We associate them with both affluence and influence, the power to live as they want and the power to make things happen in the world.

And yet, power itself is not what it used to be. My friend Larry Gross (a veteran screenwriter and one of Hollywood's sharpest minds) has convinced me that there is a new and profound cultural problem to contend with: as a society, we no longer understand power. The power of kings and dictators was always visible, tangible, understandable. The power of elected officers is by definition (if not always in reality) an expression of popular power. But the power of mega-corporations is as faceless and nebulous as it is pervasive. It hides in plain sight and communicates in code. Even the most powerful people in the world now seem harder to understand. George Bush is not the figure of gravitas, wisdom and trustworthiness we need a president to be. Bill Gates is not the charismatic, visionary egomaniac we expect the richest man in the world to be. They are ciphers, and they make their very power unintelligible. And so not only do we feel more powerless in front of a more absolute power, but we also feel unable to "relate" to it at all.

Celebrity trials provide people the sense of witnessing a form of history up close and personal. But the cultural dynamics represented in the trials always point to the fact that celebrities are ultimately "weird," and that mere mortals getting too close to them are (intentionally or not) inviting trouble -- which means they must also be weird. What we understand about celebrities is ultimately that we do not, cannot, understand them.

It's a tragedy of unknowing and incomprehension, suggesting the larger tragedy of incomprehensible power.

Shares