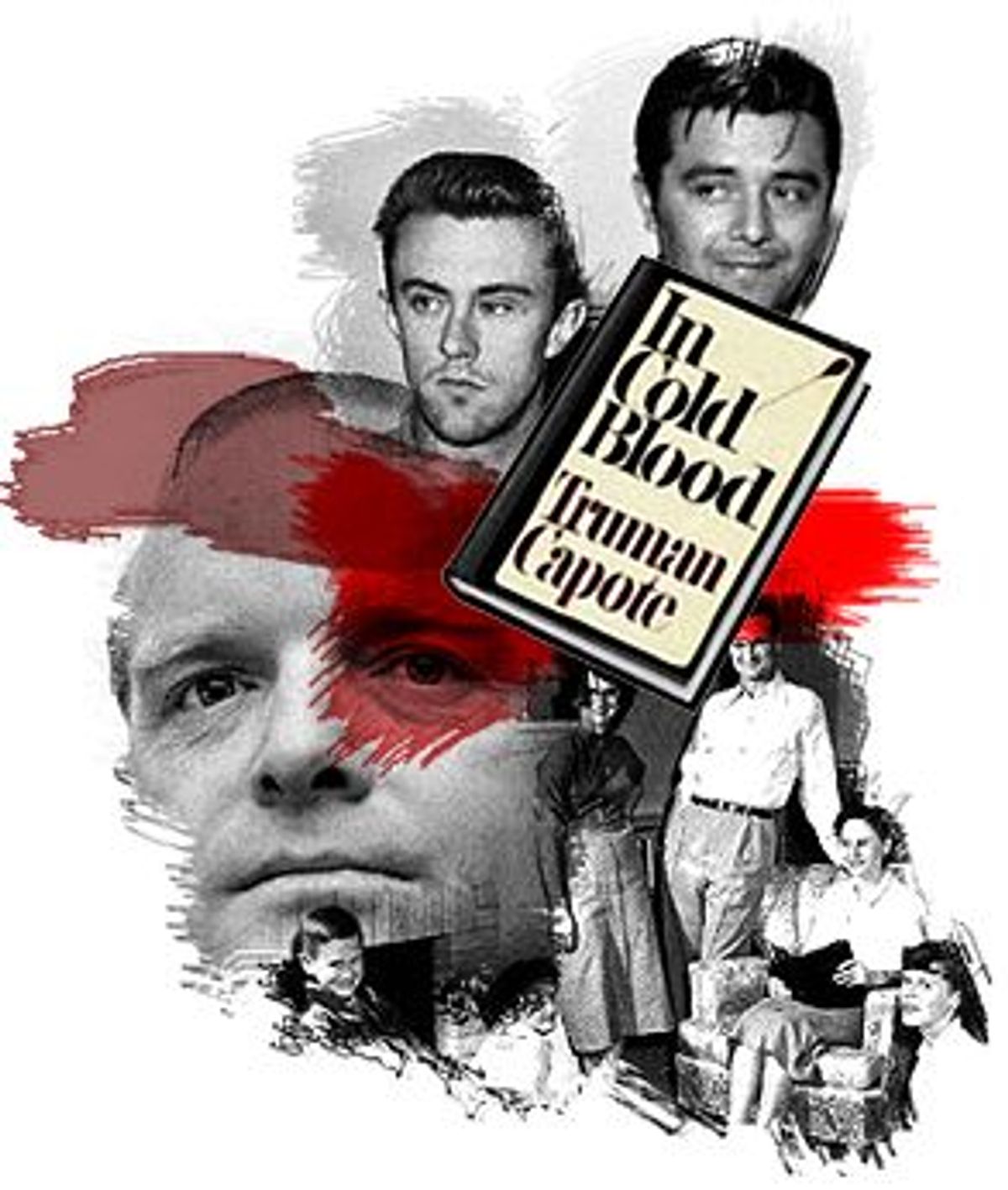

"In Cold Blood" began, as the story goes, when Truman Capote came across a 300-word article in the back of the New York Times describing the unexplained murder of a family of four in rural Kansas.

"Holcomb, Kan., Nov. 15 [1959] (UPI) -- A wealthy wheat farmer, his wife and their two young children were found shot to death today in their home. They had been killed by shotgun blasts at close range after being bound and gagged ... There were no signs of a struggle, and nothing had been stolen. The telephone lines had been cut."

Capote seized on the grisly story and went down to Kansas to turn it into a book. He spent six years researching "In Cold Blood," and claimed to have invented a genre, the nonfiction novel; later, Tom Wolfe and others would include "In Cold Blood" in their own movement, known as New Journalism.

Both inventions are old hat now, and, more than 35 years after its publication, "In Cold Blood's" radicalism is a lot less apparent. But still the book stands out as a masterfully controlled recounting of murder and its aftermath and the people involved.

Gossip-slinging and accusations swirled about Capote in the sensational months after the book's publication in late 1965, all of it a mere harbinger of the even nastier gossip and accusations that would cloud his later life. But there's no hint of that in Capote's best novel. His meticulous, even obsessive reporting allowed his characters to tell the story, and the result is the best true-crime novel you ever couldn't put down.

Herbert Clutter was a successful farmer and community leader, a man known for his fairness, his loyalty to his invalid wife and his aversion to dealing in cash. (That was a fact that, had it been known to his future assailants, might have kept all four Clutters alive.) The family is almost too much of a 1950s fantasy to be believed. Nancy, a straight-A student and award-winning pie-maker, was dating a high school basketball star.

Kenyon, the bookish youngest Clutter, was building a cedar chest to give to his oldest sister, Beverly, on her wedding. They were regular churchgoers, active in the 4-H. As Holcomb residents would later tell detectives, there was no one who didn't like the Clutters.

Their killers came from as different a world as you could find in rural America at the time. Perry Smith's family was broken and violent. He'd lost two siblings to suicide, and a parent to alcoholism. Half-Cherokee, half-Irish, Smith had a "runty" build, thanks to a motorcycle accident that left him with disfigured legs and an addiction to aspirin and glorified daydreams. It was one of those daydreams that sent him out to the Clutter place: Perry's favorite movie was "The Treasure of the Sierra Madre," and he was certain that if he could only get to Mexico, he'd find treasure of his own there.

Dick Hickock's ambitions were slightly less delusional; he just wanted to take the money and run off somewhere he wouldn't be found. Hickock was also scarred; a car accident had put an unnerving asymmetry into his otherwise handsome face. Hickock's family was poor but relatively stable. He had a penchant for passing bad checks, but the Clutter murders left his family confounded. Where did such an ordinary boy muster up so much evil?

Hickock had learned about the Clutter family from a jail mate, an ex-employee of Herb Clutter's named Floyd Wells. In prison, Wells had casually mentioned how his former boss spent $10,000 a week to keep his farm going, and speculated that there must be a safe somewhere on Clutter's considerable spread. Hickock took this wishful information and recruited Smith, a man he figured to be a natural-born killer. (This, too, was somewhat divorced from reality: Smith bragged about having once killed a man just because he felt like it, but it was a lie.)

After the two got out of prison, they drove 400 miles out to the Clutter ranch, hogtied the family members in separate rooms and demanded to know where the safe was. There was none. Hickock and Smith shot each of the four Clutters in the head and left the ranch with $40, a radio and a pair of binoculars. Two months later, Wells' information led the police to Hickock and Smith as the two pulled into Las Vegas, broke and on the run. Five years after that, both men died on the same night on the gallows of the Kansas state prison. Finally, the story had an ending. Capote could finish his book.

After "In Cold Blood" was published, Capote's friends and detractors (and he had plenty of both) would remark on the parallels between the author and Perry Smith, the more sensitive and guilt-ridden of the two killers. Possibly, Capote felt a physical kinship to Smith: His body, as one of his "swans" would later recount in George Plimpton's "Truman Capote," combined a boyish face and torso with "the legs of a truck driver." More likely he simply understood that what separated him from Smith, more than anything, was luck.

Capote, like Smith, had been born to absent, unreliable parents. Both had suicide and alcoholism in the family. Both were desperate for acceptance, but they also had ironclad estimations of their own importance -- Perry, in his words, was "special"; Capote, in his own, "a genius." Were it not for his mother's second marriage and his own considerable charms and angelic good looks (and his keen ability to ingratiate himself to his benefactors), Capote might have ended up as alone and desperate as Smith did. Like Smith, Capote knew exactly what he wanted to be, and he constructed himself accordingly. Capote's ambitions were realized; Smith's weren't.

Another claim, this one circulated by one of the detectives Capote interviewed in Kansas, had Capote involved in a sexual affair with Smith, carried out during Capote's visits to the penitentiary. That one's pretty dubious, but Capote's sympathies are clear, and his ear for Smith, and for all the disappointments of Smith's life, are part of what make the book work so well. Through Capote, we hear of Smith's studious attempts at self-improvement, his handwritten vocabulary lists full of words like "ostensibly" and "depredate."

We hear how the elementary school dropout taught himself beautiful handwriting, and an appreciation of Thoreau. This is where Capote's journalism -- not his writing, but his reporting -- comes alive: when we hear Perry Smith remembering what it was like to be reunited with his itinerant, absent father, "like when the ball hits the bat really solid. Di Maggio."

Capote knew how gut-clenchingly suspenseful dialogue could be. "In Cold Blood" recounts the scene at the Clutter house twice: first in a quote that spans six pages, delivered by Nancy and Kenyon Clutter's English teacher, Larry Hendricks, one of the first people to find the bodies.

Then, 200 pages later, from Smith's taped confession, another quote spanning several pages, broken only by the interrogator's questions. In both of these crucial chapters, Capote restrains himself to only the barest of observations, as in this part, just as Smith begins to describe the first of the murders: "Perry frowns, rubs his knees with his manacled hands. 'Let me think a minute. Because along in here, things begin to get a little complicated. I remember. Yes, yes.'" You brace yourself for what comes next.

Of course, keeping that degree of aloofness meant that Capote had to leave a lot out of the story -- for instance, the awe and resentment the residents of the small Kansas town of Holcomb felt at the appearance of a high-flying reporter. Capote was smart to bring his childhood friend Harper Lee with him to help gain the confidence of the locals. But that didn't make them like him any more when "In Cold Blood" came out.

It wasn't until Plimpton did his own Kansas reporting for his biography of Capote that we hear Harold Nye, a Kansas Bureau of Information agent, describe visiting Capote and Lee in their hotel room and finding Capote lounging around in a "pink negligee, silk with lace." Quite possibly this is made up, but it goes to show how dramatic the culture shock was for everyone involved, and how it was all the more remarkable, then, that Capote came out of Kansas with so much story to tell.

Capote was a good listener. It's what earned him the confidence of the society ladies in Greenwich, Conn., and Manhattan, and it's what made him a good reporter. His accounts of Smith's small, paradoxical kindnesses to the doomed Clutters, like when he places a pillow under Kenyon's head before putting a gun to his temple, are a hundred times more effective in describing the tumult of emotions in a criminal's mind than an expert's analysis could ever have been.

Smith's divided conscience, what allows him to stop Hickock from raping Nancy Clutter, then go on to kill her anyway, and then, later, his infamous recollection of that night, "I really admired Mr. Clutter, right up until the moment I slit his throat," could be no starker from any mouth but Smith's own.

Today, it's hard to imagine what journalism was like before Capote and the others started looking closely at "ordinary" people, before they began making an earnest effort to, as Wolfe puts it, "deliver this felt sense of the quality of life at a particular time and place." At the time, though, a lot of other people in the literary world were dubious. New Yorker critic Renata Adler snottily summed up New Journalism as "zippy prose about inconsequential people," and it's a charge that most New Journalists, and Capote certainly, wouldn't have gone too far out of their way to deny. The lives of "inconsequential people," especially those caught in consequential events, have been fascinating readers for years -- both before Capote and the New Journalists and after.

Most recently, it's what drove so many people each day to the Portraits of Grief section in the New York Times. And it's part of the reason we continue to try to make sense of the psychology of crime -- even crime on such a horrific scale as the Sept. 11 attacks. And as for "zippy prose," as Wolfe pointed out in "The New Journalism," one need only try to imagine its opposite.

Shares