The American South likes to sequester its vice, tucking away temptation on barge-casinos or inside the lap-dance palaces out on the strip leading to the airport. As for roadside attractions, there's nothing that gets the blood racing like a motor court on the other side of the state line. As a Tennessee debutante of my acquaintance once explained, "Mississippi motels are where Memphis goes to sin." Could anything be more wicked than Magic Fingers and rates by the hour?

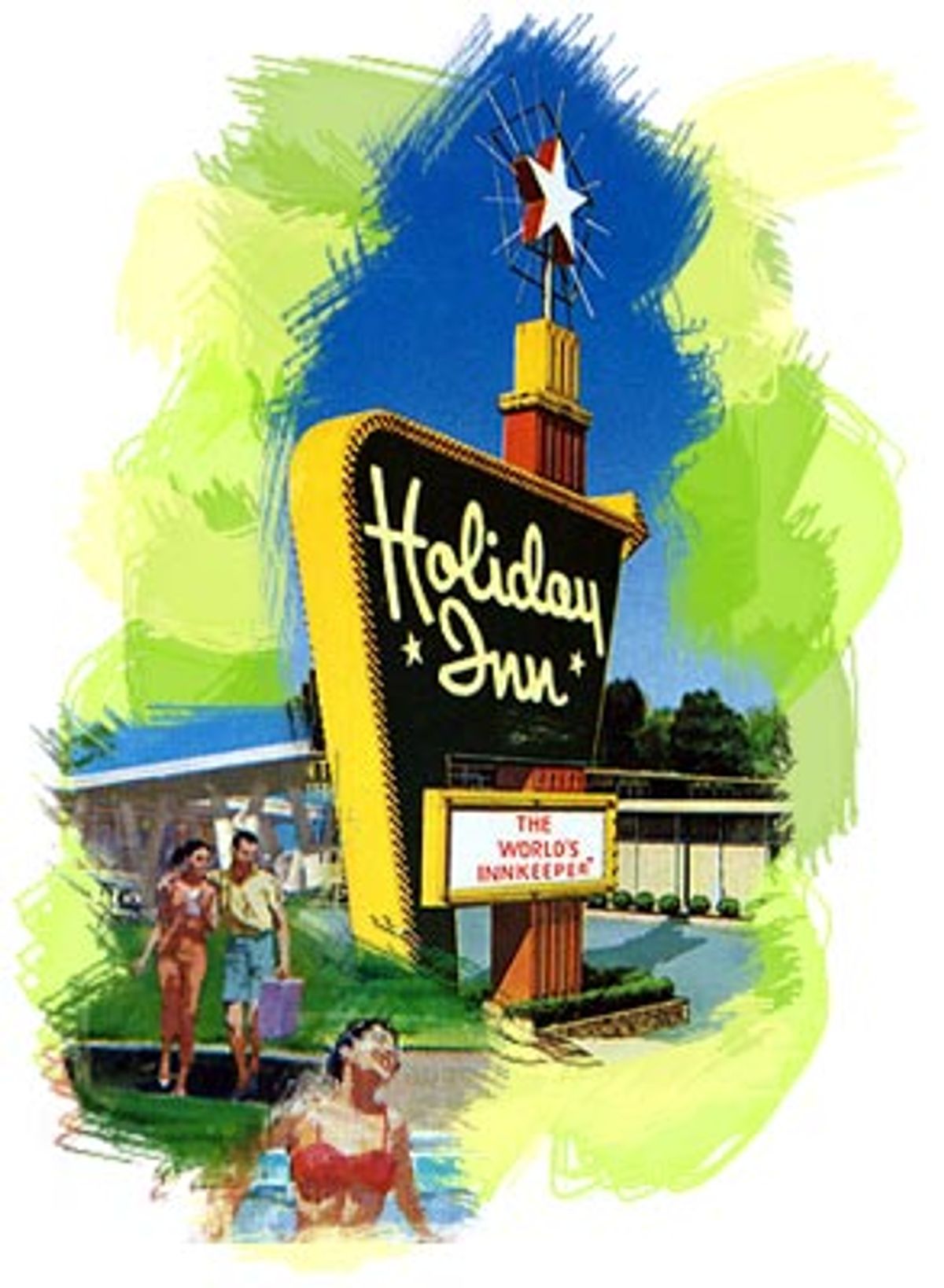

Apparently not in the Bible Belt. Yet it was a Memphis company named Holiday Inn that became a global brand by polishing the roadside hostel's image as a place where one got a good night's sleep and not a right good rogering. The company's mission was embodied by its "Great Sign," a glowing, exploding supernova of light and neon built to draw drivers off the highway and into its rooms while spelling out the purity of both its ideals and its bed sheets.

"Holiday Inn's sign was a prop in a play," says Andrew Wood, professor of communication studies at San Jose State University and an authority on motel history. "It communicated the playfulness, fantasy and optimism of the American roadside. And it meant safety for the [traveling] middle class."

The Great Sign was brash, bold and a masterpiece. It is also, alas, extinct. The company ripped them down in a bid to be a little more upscale.

Fifty years old this year, Holiday Inn is now a cultural touchstone without its icon. Few people recall or care about the company architecture, but everyone remembers the sign. Designed by the Cummings Company of Nashville, the signs were bright as blazes, built to be visible from Dwight Eisenhower's new interstate highway system.

Their marquees sported an emerald green curvilinear field with a big white neon "HOLIDAY INN" done in casual script. This was affixed to a red pylon atop which a yellow star exploded its energy into the night. Meanwhile a winking Vegas-style arrow pointed tired travelers to the office while an illuminated window box below advertised rates and local gatherings such as "Opaloosa Elks Fish Fry" or "Welcome Burlington High Senior Prom." The kinetic radiance turned the Great Sign into a symbol of American razzle-dazzle, for-sure-buddy-can-do optimism. To borrow a turn of phrase from President John F. Kennedy, another icon of the times, "the glow from that flame can truly light the world."

And it all started with a summer vacation from hell.

In 1951, Kemmons Wilson, a Memphis entrepreneur, took a family trip to Washington, D.C., and was appalled at the choice of fleabags on offer: Greasy motels, low-rent tourist camps and by-the-week boarding houses filled with persons of ill repute and encyclopedia salesmen.

The Wilson family's dilemma was not an exceptional one. Like Rizzo, the fast girl in "Grease," the motel industry developed a reputation early in life. The modern mo(tor) (ho)tel started in the 1920s as mom-and-pop motor courts for the auto pioneers traversing America in their tin lizzies. The courts were usually set on a town's outskirts and featured a cluster of small cabins. Their anonymity made them favorite trysting places (known in the industry as the "hot trade") or hideouts. Bonnie and Clyde were frequent guests. The hostels' Petri-dish potential for breeding lust and larceny alarmed FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, who demonized motor courts as "camps of crime" in a 1940 magazine article.

Wilson's idea was to get the sleaze out. He built a series of identical motels within a day's drive of each other that were intended to deliver a standardized experience, including clean sheets, air conditioning and a Bible in the bureau drawer. Throw in a pool for the kids and TV for adults (or was it the other way around?). A draftsman who had seen a 1942 Bing Crosby film penciled a name atop the blueprints: "Holiday Inn." The first one opened on Summer Avenue in Memphis, Tenn., in 1952, near what would become Graceland.

The beacon and the bait was, of course, the Great Sign. It lured station wagons into the parking lot as confidently as the Pharos lighthouse, that wonder of the ancient world, guided galleys into Alexandria's harbor.

John English, a Los Angeles architectural historian who specializes in commercial buildings of the mid-20th century (a style also known as Googie), says the Great Sign was a great communicator.

"This was not just a sign; it was an icon known around the country," he says. "Its idea was simple: 'Welcome. Enter. Sleep Here Now.'"

America's travelers checked in, in droves. Holiday Inn expanded as freeway cloverleafs bloomed over the continent. The chain leapfrogged oceans. Today there are more than 1,000 Holiday Inns in the United States and in 70 countries around the globe, the most recent a resort in Tunisia. The Great Sign -- not Elvis Presley -- became Memphis' first global brand. American business hailed Wilson as "The Father of the Modern Innkeeping Industry." He is still alive at 89, although he no longer runs the company. His biography, "Half Luck and Half Brains," tells his story.

The company lit its time in other ways. As Holiday Inn imposed order on the American road, standardizing and sanitizing the motel room, Washington was attempting the same thing in Europe, by way of NATO and the Marshall Plan. The collective enemy: Dirt, immorality and communism. Is your bathroom breeding Bolsheviks? Not at Holiday Inn, which fought the Cold War with sanitized toilet seat covers and the Great Sign. Of course, the spires of Moscow and Stalingrad also twinkled. But their stars were red, not gold.

The sign and its symbolism -- prosperity and a worry-free road trip -- was widely imitated. Then a funny thing happened. Holiday Inn lost its nerve. As the '50s became the '60s and then the bittersweet bad-ass '70s, Holiday Inn began playing it safe. In 1975 executives came up with a new slogan to express its new conservatism: "The best surprise is no surprise."

In an era of earth tones, puka shells and shag haircuts, the old Holiday Inn sign seemed dated and loud, like Dean Martin or the bossa nova. Architect John Portman introduced soaring atrium lobbies and exterior elevators to the lodging industry. They called it the "Jesus Christ" school of architecture. Crane your neck to take in a hotel's 50-story lobby and that's what you said. Sign graphics calmed down; Helvetica and Geneva became the hot type fonts. All this was clean, correct and fashionable, but to English and other aficionados it was the death knell for bawdy mid-century modernism.

"Good taste is a very dangerous thing," says English. To the "Keep America Beautiful" crowd, he observes, the Great Sign "was considered garish, tacky crap that was destroying our cities."

In 1982, the Great Signs came down. In their place rose dinky, back-lit plastic ones. The new signs were tasteful, of course, but they weren't much fun.

"They remodeled a classic Mercedes and got a Geo Metro," says Dickson Keyser, a principal in Idee, a San Francisco design firm specializing in architectural signing and graphics for clients from Siebel Systems to Stanford University.

In 1990, Holiday Inn was sold, and became another cog in the giant British conglomerate Bass PLC, since renamed Six Continents PLC. Holiday Inn is now efficient and boring, its onetime entrepreneurial exuberance squeezed out by yield-management techniques and greater return on investment. Wood, of San Jose State, calls this perfected state "omnitopia," a place of "ubiquitous, ever-present environments."

"It's like downloading the same home page whereever you go," he says. In omnitopia, a guest doesn't check in to a room. She checks in to a node.

The irony, of course, is that the company's efforts to appear modern have only dated it. Today plastic, rough concrete and ficus trees are of scant interest to aging boomers.

"It's like, hello," English says, "1980s green awnings and brass fern bars are long over. Wake up."

Consumers hunger for nostalgic yesteryears and get them in products of faux-'50s and '60s design, like Johnny Rockets soda fountains and the Austin Mini. They pay top dollar, too. Parabolas and boomerang-shaped design elements are found in newly gentrified downtown entertainment districts, not out on the suburban business loop. Might the Great Sign, like Liza, stage a comeback?

Fat chance, say the experts. It's unlikely any original Greats remain intact.

"They were cut into pieces," laments English. "Demolished. Recycled. And gone."

He predicts Holiday Inn will cobble together various design elements from all eras. The result, he predicts, will be a Franken-sign, a symbol neither evocative of the old nor symbolic of something really new.

"They'll bring them back, but not in the right way," English says. "There's so much caution, and corporations are afraid of being perceived as too wild or associated with the past."

Meanwhile, we can hold out hope that some brave marketing VP or a lucky discovery behind an old barn will mean a resurrection. Then, perhaps, the American night will glow with exploding stars, dancing colors and neon letters blinking "NO VACANCY" once more.

Shares