It's been a movie 18 years in the making. In fact, it's now a pair of movies. Get ready for the West Memphis Three, times two.

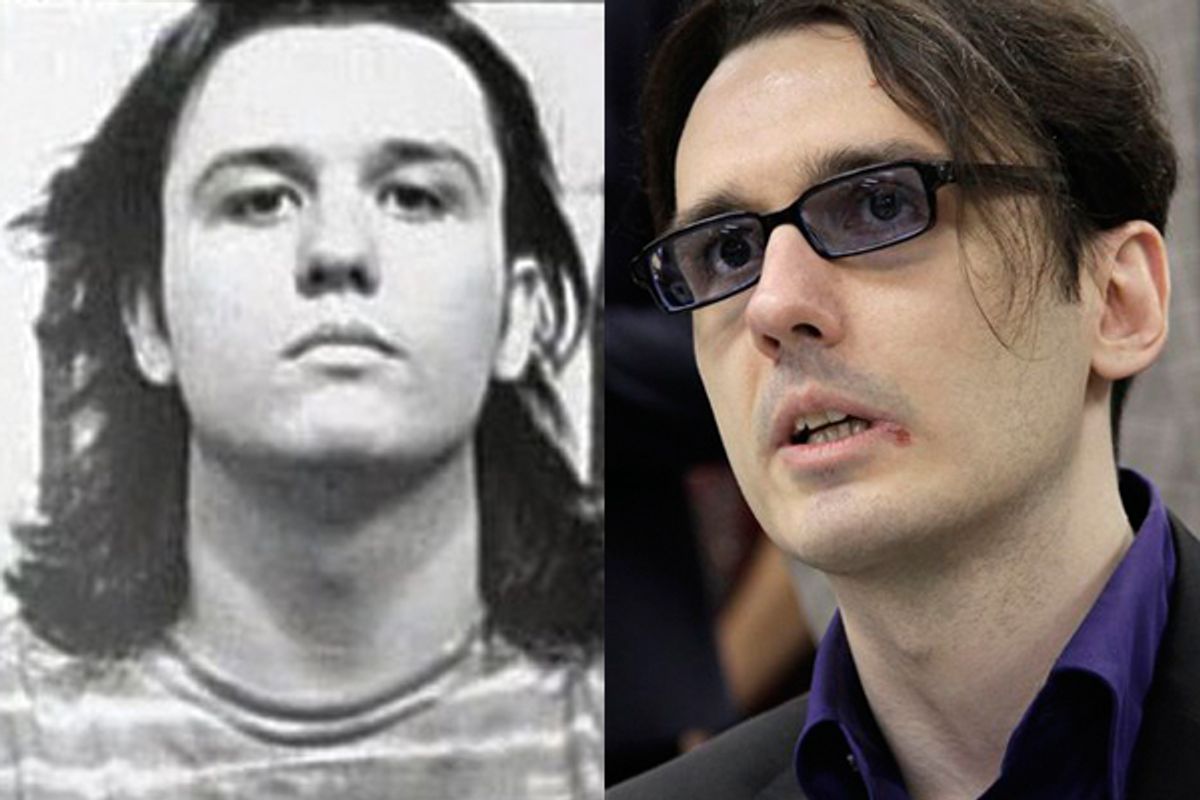

In May 1993, the naked bodies of three young boys were found hog-tied in a ditch in the Arkansas woods. The crime appeared to have the additionally heinous elements of sexual abuse and ritual torment. And soon three older boys, Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley, teenagers who shared a troubled history of petty crime and a fondness for heavy metal and Stephen King, found themselves chief suspects in a triple murder. They were convicted, based largely on a confession coaxed from Misskelley, who is mentally handicapped. He later recanted, but was nonetheless sentenced to life plus 40 years for the crime. Baldwin got life as well. Echols was sentenced to death.

Yet the story didn't end with a trio of misfits going off to prison, or with a tidy sense of justice for a shattered community. In the ensuing years, the story of Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley has become an ongoing source of public outrage -- and an inspiration for filmmakers and musicians. In 1996, HBO Films and directors Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky released "Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills," the haunting, exasperating tale of a nightmarish crime, Satanist hysteria, and three black-clad boys sent away forever. The movie was a sensation, and resparked criticism that the investigation and trial were wildly botched at best -- and at worst, deliberately unfair.

Yet even a 2000 sequel, with updates on the case and the grim fates of the West Memphis Three, failed to move the Arkansas judicial system. Still, the convicted men continued to attract supporters like Eddie Vedder, Peter Jackson, Henry Rollins and Johnny Depp, along with legion of non-celebrity supporters, including the mother of one of the young victims and the father of another. High-profile supporters performed star-studded concerts for the trio's defense fund. Yet the judge in the trial, David Burnett, steadfastly refused to reopen the case, saying of Echols that "My court is through with him; if he wants to appeal he will have to take it to the Supreme Court, which I'm quite certain he will."

But in a surprise move on Friday, the three were allowed to proceed with an unusual gambit known as an Alford plea, in which a person pleads guilty but still can maintain his or her innocence. And with that, they were freed.

The Alford plea -- and its acceptance by the case's new judge, David Laser -- likely had something to do with the mounting DNA evidence suggesting that the three were not connected with the crime. A new hearing had been scheduled for December, at long last. It's far from a full victory for the three, who have still not been exonerated of the crimes. As Baldwin said on Friday, "This was not justice. In the beginning we told nothing but the truth. We were innocent, and they sent us to prison for the rest of our lives."

Frustrating though it still is, the story does at least now have a far more satisfying resolution than the one it long seemed destined for. And that's got to be sweet for "Chloe" and "Sweet Hereafter" director Atom Egoyan, who's making a dramatic version of Mara Leveritt's 2003 book "Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three." The film had been stalled for years, but is set to begin shooting next spring. On Saturday, Egoyan told the Hollywood Reporter that the new developments "unquestionably ... will have an effect on the way the movie is seen ... [It's] very exciting news, obviously; quite shocking and sadly predictable."

But perhaps the most cinematically satisfying story belongs to Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, who will show their latest film, "Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory," next month at the Toronto International Film Festival. That film was completed before Friday's developments, but the filmmakers hope to have a new ending shot in time for the New York Film Festival in October. The film will air with a fully updated ending on HBO in January. "I'm glad it's over," Berlinger told the Hollywood Reporter Friday. "Because I really didn't want to make a fourth film."

What happens next for the West Memphis Three remains to be seen, though the fight to clear their names goes on. And justice is far from served. As Egoyan says, "What's wonderful is that these young men are free. What's terrible is that justice has not been done for the three young victims." Movies -- and often juries -- insist upon resolution. Reality instead offers complexity, ambiguity, doubt and unfairness. But on Friday, Damien Echols issued a statement that read in part, "This whole experience has taught me much about life, human nature, American justice, survival and transcendence." It's far from a happy Hollywood ending. But it's a hell of a heartbreaking drama.

Shares