I'm tempted to describe "The Extra Man" as an intriguing little movie that doesn't totally work -- but doesn't that rather patronizing dismissal assume that I understand what it's trying to do? If you've seen writing-directing duo Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini's other films, including "American Splendor" and "The Nanny Diaries," you'll already know that they favor a brand of astringent, character-based comedy that isn't easy to describe and, for good or ill, isn't quite like anything else.

"The Extra Man," adapted from a novel by Jonathan Ames, spins a shaggy-dog yarn about Louis Ives (played by Paul Dano), an eccentric young man who seems to have missed his mark in history by 80 years or so. It's no accident that Louis spends an early scene defending Nick Carraway, the personality-free narrator of "The Great Gatsby," against the charge that he's boring. (Louis' own story is also narrated, from time to time, in the plummy, camp-Brit voice of Graeme Malcolm.) Louis loses his job as a prep-school English teacher after an incident involving some purloined ladies' underthings (which is exactly how he would put it) and moves to Manhattan to pursue his dream of becoming the next Scott Fitzgerald, or, more to the point, of becoming Nick Carraway. Possibly Nick Carraway in lingerie.

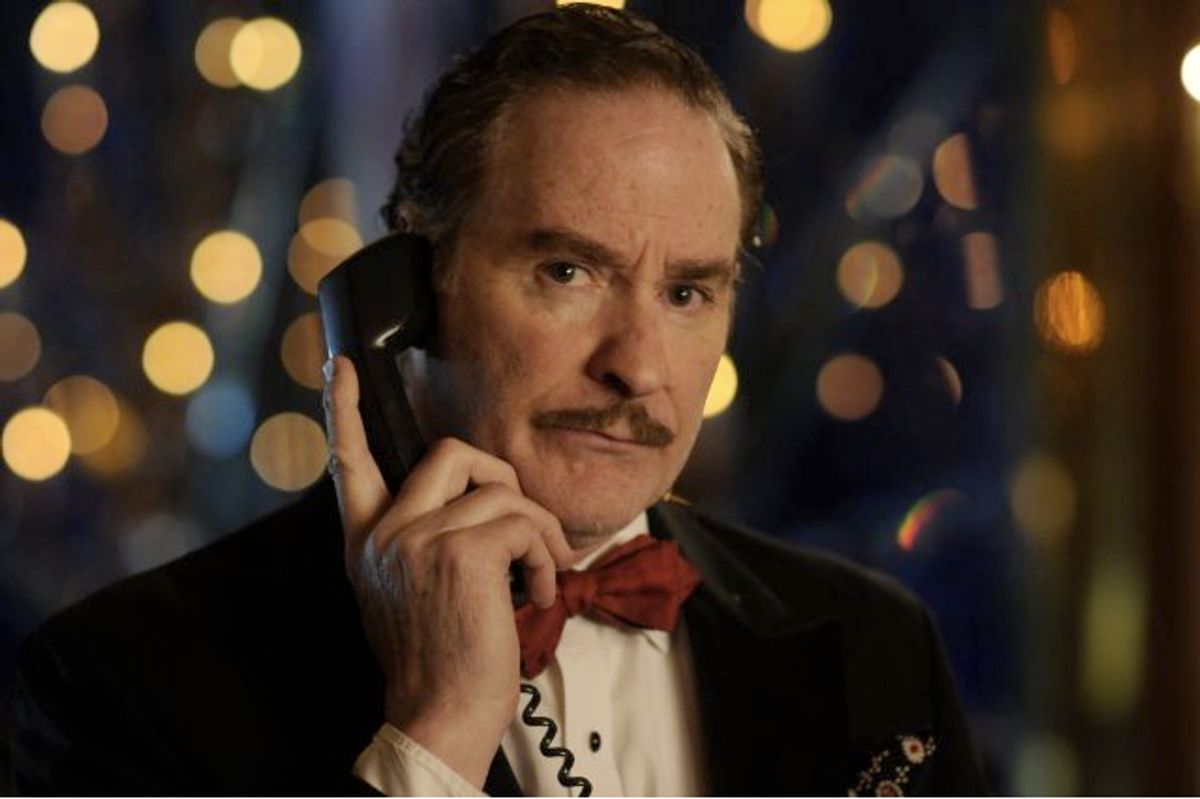

You might assume that this is not a fulfillable yearning in 21st-century New York, but then you haven't met Louis' new roommate, who himself seems to inhabit an alternate dimension that is not exactly that place and time. If there's a reason to recommend "The Extra Man," a movie as lip-puckeringly dry as a cocktail of lemon juice and baking powder, a movie that seems determined to thwart all the viewer's desires, that reason is Kevin Kline's performance as Henry Harrison, the destitute but semi-debonair playwright who takes Louis under his wing.

A combination of money-grubbing vulgarity and tremendous, pretentious refinement, Henry is the living and breathing embodiment of a social type my father used to describe as "carnation in the buttonhole, no underwear." He makes a living, such as it is, by mooching off elderly rich women as an escort or "extra man" (aka "walker"). Is he a gigolo, in effect or in fact? Is he gay? All I can tell you is that these questions come up. Am I issuing a spoiler in saying that this is not the kind of movie that cares much about answering them?

Like all truly ludicrous people, Henry has no self-pity and no sense of his own silliness. He is determined to live life according to his own sense of decorum -- and his own Taliban-esque right-wing Catholic moral code -- and the rest of the world can (and certainly will) go to hell. Men do not sit across from each other at meals; even at the corner coffee shop, Louis and Henry must sit in adjacent booths. The corrosive force of coeducation has ruined American literature, Henry thinks; he sees a great future for the sex-segregated worlds of Orthodox Judaism and fundamentalist Islam. ("The women I like best are the Hasidic women -- they really get it!") He answers the phone by saying "H. Harrison!" in a tone of great authority, and you just know he's got some theory about why that's more appropriate than simply saying "Hello," or using his full name.

It's easy for a skilled actor to play an outlandish, larger-than-life character to comic effect, but not half as easy to make him seem like a real person who has his reasons and his own internal compass, deranged as it may be. When you spend enough time around actors, you figure out that every role has personal resonance; that's how the whole enterprise works. But in this case it's well-nigh impossible not to see Henry -- once a promising young writer, now reduced to painting fake socks on his flea-bitten ankles -- as a parody or pastiche version of Kline himself, who spent three decades manfully resisting Hollywood's efforts to turn him into a movie star and now is definitively too old for the job. (He's 62.)

When Kline emerged from the Juilliard School and the New York theater scene in the late '70s, he was widely regarded as the finest young American actor of his generation. That's no exaggeration; Frank Rich described Kline as "the American Olivier" during his long run as a star of the New York Shakespeare Festival, and the comparison seemed apt. He had the training, chops and natural verve to play Hamlet, Henry V and Sir John Falstaff, along with the charisma and flexibility to play contemporary screen roles. Yet somehow, across two dozen films in the '80s and '90s, his long-forecast stardom never arrived. Kline was overwhelmed by the Oscar-winning histrionics of Meryl Streep in his first movie, "Sophie's Choice," and it's as if he's been half in the shadows, playing second bananas and pompous-comic villains, ever since.

I am not suggesting that Kevin Kline is some kind of failure, and still less that he lives in a filthy apartment, paints his feet with shoe polish and drives a rusted-out Buick Electra. (Kline and his wife, the actress Phoebe Cates, do indeed live in Manhattan with their two children. I suspect that's where the similarity ends.) He's had a tremendous career that isn't anywhere near over; he returned to the stage recently to play both Cyrano de Bergerac and King Lear, and plays Edwin Stanton (Lincoln's secretary of war) in Robert Redford's forthcoming "The Conspirator." He's won two Tonys and one surprising Oscar (quick, without looking: What was the movie?) and is so clearly a person of integrity and taste that you have to assume he was right to turn down Tim Burton's "Batman," along with the other non-roles that gave him the Hollywood nickname "Kevin Decline."

No, Kevin Kline is not Henry Harrison, and vice versa. Henry is presumably a more pathetic and desperate person than Kline ever was or ever will be -- although Kline has joked about his acting-school vow never to do soap operas or commercials, a vow he broke as soon as he faced poverty. Still, Kline is something like a vastly more successful showbiz version of Henry, a guy who has steered by his own antique and subjective code, even at the risk of appearing ridiculous, or of actually being ridiculous. Kline has held onto his dignity in a profession that demands that you abandon it as the price of fame, and in that sense he's the best role model for young actors you could want, just as Henry, even in his disheartening and decrepit condition, is in some sense the right mentor for a young literary aspirant torn between the desire to be a gentleman and to be, um, a lady.

Given that "The Extra Man" could be described as a movie about a wannabe transvestite who moves in with an aging gigolo, it's relentlessly unwacky and even quietly subversive. There are lots of directions this story could go -- a coming-out story, a gay love affair, a hetero romantic comedy, a writerly coming-of-age yarn, a "Cage aux Folles"-style transgender farce -- and Berman and Pulcini feint in all those directions before settling on a cast of oddballs (also including John C. Reilly speaking in falsetto, Marian Seldes as a nonagenarian dowager, and Katie Holmes in a nothing ingénue role) and a comedy of manners so subtle it almost isn't there at all. You'll either find "The Extra Man" utterly charming or thoroughly mystifying, but either way Kevin Kline, playing a community-theater version of himself, with all the foppishness and Shakespearean pretension but half the talent and none of the luck, inhabits its peculiar soul.

"The Extra Man" opens July 30 in New York and Santa Ana, Calif.; Aug. 6 in Berkeley, Calif., and Los Angeles; Aug. 13 in Boston, Chicago, Minneapolis, New Haven, Conn., Palm Springs, Calif., Phoenix, San Diego, San Francisco and Seattle; Aug. 20 in Atlanta, Denver, Hartford, Conn., Philadelphia, Portland, Ore., Santa Fe, N.M., and Washington; and Aug. 27 in Detroit, Gainesville, Fla., and St. Louis, with more cities to follow. Also available on-demand from Direct TV, Dish Network, Amazon and other providers.

Shares