For some obvious reasons and others we can guess at, quite a few 21st-century filmmakers seem drawn to the shadowy and outrageous history of 1960s and '70s radicalism, especially at its outermost fringes. "Carlos," the dazzling, epic-scale movie and/or mini-series from French director Olivier Assayas, is the latest and probably greatest example, but it's definitely not alone. In the last few years we've also seen Steven Soderbergh's "Che," Uli Edel's Oscar-nominated "Baader Meinhof Complex," Japanese director Koji Wakamatsu's docudrama "United Red Army" (never released in the United States) and Italian director Marco Bellocchio's "Good Morning, Night." (It might be stretching the point to include Steven Spielberg's 2005 "Munich," but it's definitely related.)

What's going on here? Is this just dewy-eyed, aging-leftist nostalgia for the long-ago days of nutso revolutionary internationalism? I'm sure some people will respond to this wave of movies that way, but what I see is a whole bunch of dense and interesting drama, and an honest effort to reckon with a challenging history that continues to resonate in our own time. Taken together, the overlapping stories in all those movies (which are intriguing at worst, and mostly terrific) describe the deranged, cloak-and-dagger underbelly of the late Cold War era -- and remind us that 9/11 was not some isolated or unprecedented event, but another episode in a long-running, clandestine war that hardly anyone understands.

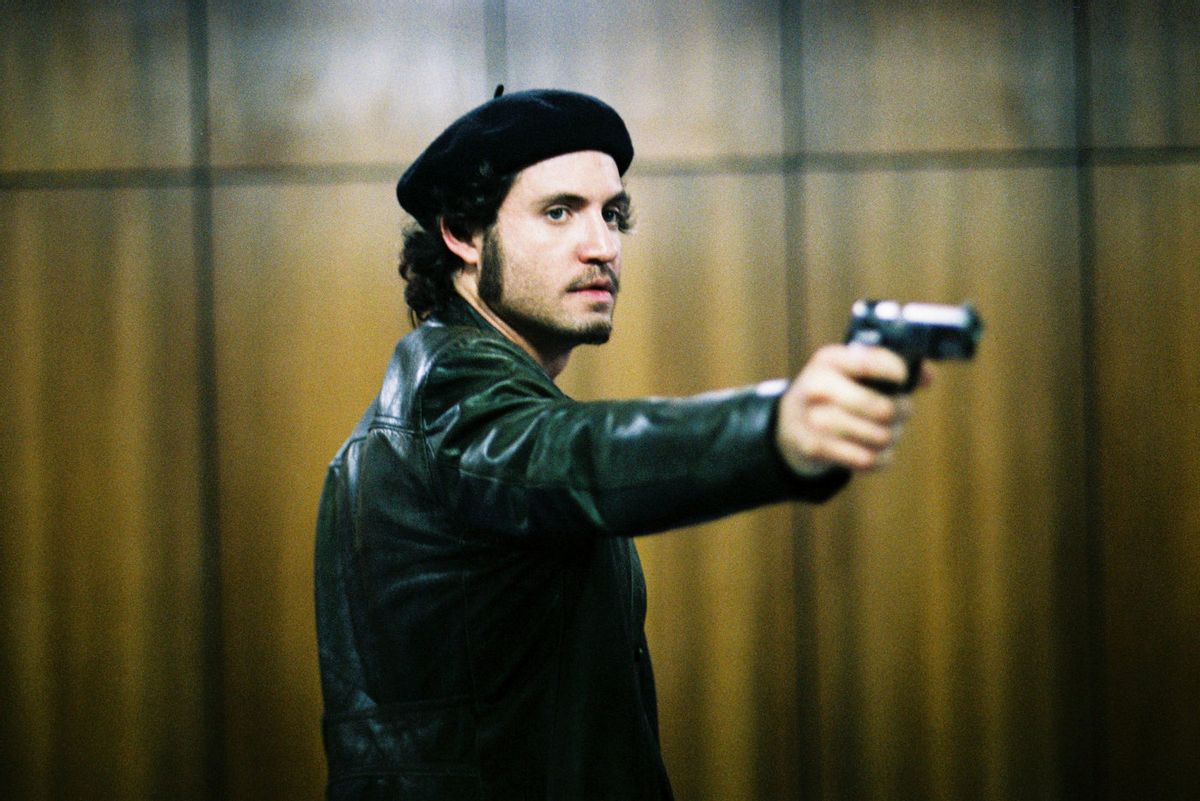

"Carlos" is an impressive international production on a grand scale, shot on both locations and constructed sets in England, France, Germany and Lebanon and delivered in many languages. (Let's see: There's dialogue in English, French, Spanish, German, Arabic, Russian and Hungarian, at least.) Far more important, it's a great yarn, a tale of violence, daring, intrigue and blindness built around the forceful and dynamic performance of Venezuelan-born actor Edgar Ramírez, who dominates the screen as his countryman and namesake Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, better known to the English-speaking world as Carlos the Jackal. (The "Jackal" part was hung on Carlos by British journalists making a spurious connection to the spy thriller "Day of the Jackal"; he never used it and it isn't mentioned in the movie. By the way, if you think Ilich is a funny name for a Latin American kid, his two brothers were named Vladimir and Lenin. It was that kind of family.)

This movie made me realize how badly art-house cinema has needed an infusion of the storytelling that has revitalized American episodic television over the last decade or so. As Assayas and co-writer Dan Franck depict him, Carlos is like the jet-set terrorist cousin of Tony Soprano, and I'm not sure that's a coincidence. Simultaneously charismatic and repellent, with an appetite for wine, women and song and a prodigious belief in his own greatness, Carlos is a mock-Shakespearean blend of cruelty, genius and vulgarity much as Tony is. There are differences, to be sure: Carlos doesn't have much of the family feeling or sentimentality that defines Tony, and Tony never pretends that his crimes derive from noble ideals. But if I read "Carlos" correctly, Assayas is arguing that Carlos' ideology was largely window dressing to cover an animalistic quest for power and notoriety.

I should back up for a minute and observe that readers under 35 may have no idea who Carlos is, and why he's important. (He may seem like a man from a bygone epoch, but he isn't dead; the real-life Ilich Ramírez just celebrated his 61st birthday in the French prison where he will presumably spend the rest of his life.) Carlos was the world's most famous and most wanted terrorist when Osama bin Laden was taking schoolboy vacations to Stockholm. Instead of Osama's nihilistic and bloodthirsty Puritanism, Carlos projected himself as an avatar of radical chic, a stylish lady-killer and bon vivant fighting Zionism and imperialism on behalf of the Palestinian people and other oppressed masses around the globe. While Carlos' purported ideology was noxious and stupid on several levels, it's fair to note that he saw no strategic value in civilian casualties, and preferred media spectacles to mass carnage.

Assayas and Franck follow Carlos through his rise and fall as the rock star of global terrorism, from his emergence in 1973 as a European operative for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (a violent PLO offshoot that viewed Yasser Arafat as a traitor to the cause) to his humiliating arrest in the Sudan -- as he recuperated from testicular surgery! -- more than 20 years later. As the film captures in fascinating detail, Carlos' career began in a vastly different cultural and technological landscape, when smuggling weapons into an embassy building or aboard an airliner was easy, and traumatized European authorities were eager to negotiate with hijackers and hostage-takers in order to avoid bloodshed.

"Carlos" offers a dizzying chronicle of names, places, back-room deals and shifting alliances; you won't make sense of it all, but that's because it didn't make sense at the time either. Carlos makes arms deals with Basque "freedom fighters" in Budapest, bickers with PFLP head Wadie Haddad at a training camp in Yemen, meets then-KGB head and future Soviet premier Yuri Andropov in Baghdad (did Andropov really ask Carlos to kill Anwar Sadat?) and comes variously under the patronage of East Germany's Stasi, Libya's Moammar Gadhafi and Syria's Hafez el-Assad. (Assayas' terrific and enormous supporting cast features Alexander Scheer as Johannes Weinrich, Carlos' main lieutenant, Nora von Waldstätten as Magda, who is first Johannes' girlfriend and then Carlos' wife, and Talal el-Jourdi as "Ali," Carlos' shadowy Syrian handler.)

Early and late in his career, Carlos works as a simple hit man, failing to murder a leading British Zionist in the early '70s (on behalf of the PFLP) but succeeding at bumping off a German-based leader of the Muslim Brotherhood in the late '80s (presumably at Syria's behest). In between, he bombed Israeli-owned banks and French express trains, sent a couple of buffoons out to Orly airport with an RPG launcher to shoot at El Al flights, and orchestrated an attack on the French embassy in The Hague. But Carlos' international reputation as the Prof. Moriarty of terrorism rests largely on his Christmas 1975 hostage-taking at OPEC headquarters in Vienna, where he was officially working for the PFLP but probably doing the bidding of Saddam Hussein.

Assayas spends a lot of time and drama on this improbable event -- almost an entire movie, in the three-part, five-hour version of "Carlos" -- and it's every bit as nutty as it sounds. Why did a pro-Palestinian militia group want to abduct a bunch of Arab oil ministers? And why did the group consist of two Germans, a Lebanese and a Venezuelan Che wannabe, along with only one Palestinian? To understand any of that, you have to travel with "Carlos" into the alternate universe of the 1970s far left, where the Palestinian cause was seen as the forefront of the global revolutionary struggle and where defeating "pro-Western" Arab or Muslim leaders like the Shah of Iran or the Saudi royal family (ha!) was even more important than destroying Israel itself.

The OPEC raid and its farcical denouement in Algiers, where Carlos discovers that the DC-9 he demanded from Austrian authorities can't fly all the way to his intended destination in Baghdad, capture many of the themes that Assayas sees in Carlos' life and career. There's the implication that he wasn't such a brilliant strategist after all, just a dude with lots of bluster and confidence who could buffalo people and sometimes got lucky. It also seems clear that Carlos' devotion to the Palestinian cause, and to revolutionary Marxism, was a matter of convenience and political posturing rather than profound commitment. (Later in his life, in fact, Carlos converted to Islam and heaped praise on bin Laden and the Iranian mullahs. Meet the new boss, I guess.)

There's no way I can do full justice to "Carlos" in one relatively short review, except to say that it's a tremendously absorbing blend of history, journalism and drama. As soon as it was over, I wanted to watch it again. Assayas is a stylish and skillful director whose earlier films ("Summer Hours," "Clean," "Irma Vep") have left me cold, but here he's made one of the signal cinematic works of our still-young century. You can see "Carlos" in various versions and contexts: The full-length, three-part version that I've seen premiered this week on the Sundance Channel and will play big-city art-house theaters, while a shorter "theatrical cut" will be more widely available. (I imagine both will ultimately be available on disc.) Either way, don't miss it.

"Carlos" is now playing in New York, in both the "special roadshow edition" (330 minutes) and the "theatrical cut" (165 minutes), with wider national release to follow for both versions. The theatrical cut will be available on-demand beginning Oct. 20, from various cable and satellite providers.

Shares