Every celebrity worth his or her salt has a semi-mystical creation legend drawn from that prehistoric period when he or she was a regular person just like us. Jim Carrey's has been repeated in every article ever written about him, so we might as well get it out of the way. One night in 1987, when the 25-year-old Carrey was a struggling Canadian comic trying to make his way through the show-biz jungle of Los Angeles, he drove his old Toyota up to Mulholland Drive in the Hollywood hills. Sitting there overlooking the City of Angels and dreaming of the future, Carrey wrote himself a check for $10 million. He dated it Thanksgiving 1995 and added the notation, "for acting services rendered."

This story has become famous, of course, because Carrey's expression of brazen optimism turned out to be conservative. By the time 1995 actually rolled around, his rambunctious goofball roles in "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective," "The Mask" and "Dumb & Dumber" had yielded worldwide grosses of $550 million, and the newly minted superstar's asking price was up to $20 million per picture. But by that time, Carrey no longer had the check anyway -- in July 1994, he had slipped it into his father's pocket as Percy Carrey, who had once housed his family in a Volkswagen camper after losing his job as an accountant, lay in his coffin.

Now that Carrey, who will turn 38 next month, has become one of Hollywood's most bankable stars, he faces a predicament something like Truman Burbank's at the end of "The Truman Show." He's free to go anywhere and do anything, but he's also hemmed in by his enormous fame and by the expectations of his producers and his audience.

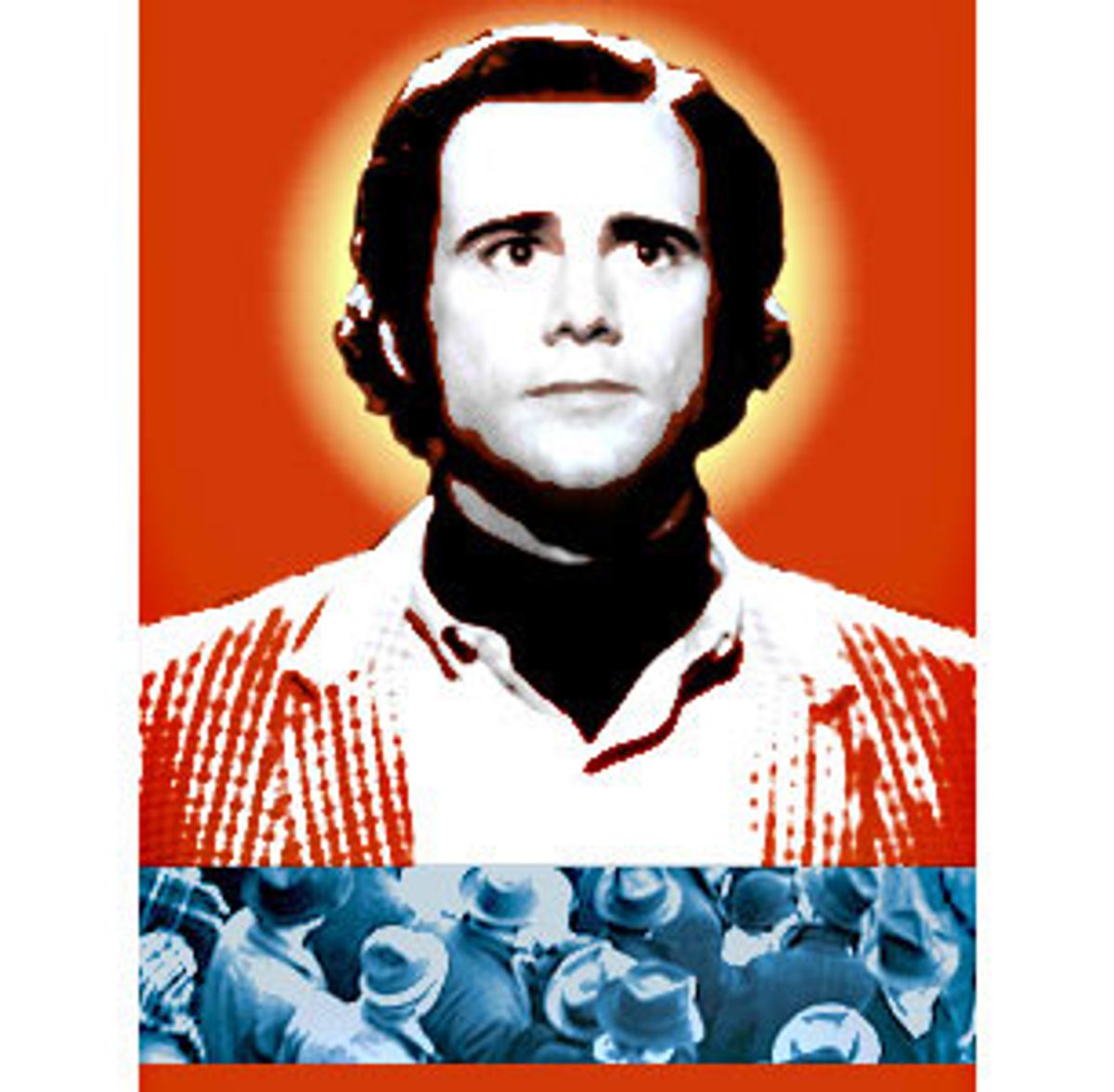

Some film critics and other middlebrow tastemakers have never forgiven Carrey for drawing huge audiences to watch him talk out of his ass in "Ace Ventura." His uncanny performance as the late guerrilla comedian Andy Kaufman in "Man on the Moon," which opens Dec. 22, may win Carrey the mainstream respect (and the Oscar nomination) he has long coveted. But the real significance of the Kaufman role in Carrey's career is not yet clear.

I see Carrey as the greatest film comic of our generation, and perhaps the finest physical comedian since the silent era of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. (Whether his movies are any good is an entirely different question.) His comedy can be juvenile, but it's almost never cynical or mean-spirited; his sympathy for the geek, the loser, the little guy, is completely unaffected. Rarely have such natural gifts for slapstick, parody and absurdism come together so gracefully in a single performer.

But Carrey's darkest and most adventurous film to date, "The Cable Guy," was widely viewed as a failure, and neither the syrupy "Liar Liar" nor the pedantic "Truman Show" displayed his talents to best advantage. As fine as he is in "Man on the Moon," I don't really want to see Carrey up on that dais in March oozing phony sincerity as he handles that statuette. If that happens, and the inevitable upscale acting roles pour in, he'll be in dire peril of sacrificing his bizarre genius to become Tom Hanks or, even worse, Robin Williams -- a former funnyman who's all grown up, a tender yet mature specimen of American masculinity. As Alfred E. Neuman would say, Yecch! Can Andy Kaufman, from beyond the grave, give Carrey the courage to avoid this fate and chart his own course?

Let's go back to Carrey's creation legend, which has several ingredients that also show up in his spectacular if uneven work as a comedian. There's a blithe self-confidence, which in one direction suggests boundless egotism and in another borders on power-of-positive-thinking naiveti. There's a classic, Chaplinesque comic narrative about the hapless, likable schmo who doesn't realize how badly the odds are stacked against him, and finally triumphs over the tyrants and the stuffed shirts through indomitable pluck. There's a frank and touching sentimentality (I don't mean that as a bad word), a passion for the grand, absurd gesture and an almost religious belief in symbols and in the power of the past over the present.

Of all these qualities, only the grand gesture seems to tie Carrey to Kaufman, the inexplicably strange comedy star of the '70s whom Carrey, director Milos Forman and screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski capture with eerie, transcendent accuracy in "Man on the Moon." You can certainly imagine Kaufman writing himself -- or maybe his alter ego, the boorish lounge singer Tony Clifton -- a check for some ridiculous amount. But Kaufman/Clifton would have insisted on cashing it. Indeed, forcing Bank of America to go through the sober ritual of bouncing a billion-dollar check drawn on a nonexistent bank in the nonexistent country of Caspiar (homeland of Kaufman's "Foreign Guy" character) would have been the point of the whole exercise. Kaufman wanted to become a star as part of a larger agenda that was somewhere between enormous practical joke and situationist event. Jim Carrey wanted to become a star, period.

But who doesn't? It isn't Carrey's fault that celebrity is the only idea of nirvana that mass culture has to offer. It wouldn't be fair to compare him with Kaufman if Carrey hadn't explicitly invited us to do so. But despite their obvious and sometimes glaring differences -- the rubber-faced physical comedian who seems relentlessly eager to please vs. the cerebral, conceptual performer who refuses to pander -- there are instructive similarities between the two.

Both were cold-weather refugees who hungrily embraced the know-thyself ethos of Southern California: Kaufman was a leading practitioner of transcendental meditation, while Carrey has been in therapy for years and reads every New Age self-help book. Both have employed the stand-up technique known as "disrespecting the room": for Kaufman, this meant forcing audiences to moo and meow along with his children's songs, while for Carrey, it inspired his dismissive catchphrase, "Well, all righty then!"

Most importantly, both are oversized comic geniuses who don't exactly fit the cookie-cutter categories of the American entertainment industry. Kaufman had at least partly succeeded in breaking free of conventional comic vehicles by the time lung cancer got him in 1984, at age 35 (since he didn't smoke, some fans believed for years that his death was a classic Kaufman hoax). Carrey, far wealthier and more famous than Kaufman ever was, seems to be invoking his dead hero as a guiding light, a star to steer by as he sails his own career into an ambiguous future.

As "Man on the Moon" makes clear, Kaufman hated TV sitcoms and only played the lovable-if-eccentric Latka on "Taxi" after he was convinced it would bring him the freedom to do bigger things. As his manager, George Shapiro (played by Danny DeVito), tells him in the film, "You make them love you now, and later on ... you can fuck with their heads all you want."

In fact, Kaufman's biggest fuck-with-their-heads enterprise, his deliberately overextended career as a bigoted, misogynist bad-guy pro wrestler -- documented in the remarkable film "I'm From Hollywood," made by Kaufman's girlfriend Lynne Margulies -- was only possible because of his stardom. As he would sneeringly remind the middle-American throngs who turned out to see him defend his "World Intergender Championship" belt, he was a television star who made more money in a week than most of them did in a year. (I trust no one will be horrified at this late date to learn that the whole business, including the feud with Memphis wrestler Jerry Lawler that supposedly landed Kaufman in the hospital, was, in wrestling parlance, a "work.")

Carrey is by anybody's definition a far more conventional performer. He's an entertainer who seems completely unembarrassed by that fact. (Kaufman sometimes thought of himself that way too, but his schizophrenic relationship to fame and the mass audience was far more complicated.) I said earlier that Carrey's comedy combines slapstick, parody and absurdism; as he would probably admit, he lacks the intellectual heft for satire, the most cerebral of comic forms.

In the 20 or so magazine interviews Carrey has done since 1991, he almost never discusses social or political issues. His frame of reference is mainly his own emotional and family life (he's notoriously confessional) and show-biz history. He isn't much interested in art or classical music or haute cuisine, and his taste in theater runs more toward Rodgers and Hammerstein than Samuel Beckett (though he'd make a great Gogo in "Waiting for Godot"). As he said to an Esquire reporter in 1995, "I don't know about anything. I'm not an expert on anything but laughs. I just know how to make people feel good."

Given all this, it's not surprising that intellectuals have tended to view Carrey as the nadir of pop-culture stupidity. (Early in his career, the enormously popular Charlie Chaplin was often seen in similar terms.) With the ambiguous and tantalizing exception of "The Cable Guy," you won't catch Carrey intentionally alienating most of his audience the way Kaufman did. Like so many comedians, Carrey came from a poor and unhappy family -- Kaufman, in contrast, grew up in middle-class comfort on Long Island -- and for all his millions he still seems to crave the audience's affection.

But there is something in Carrey that is genuinely anarchic and sometimes dark, something that's never adequately contained in his often humdrum movie vehicles and that yearns to break out. He has referred to his own style as "Fred Astaire on acid," which is certainly a perfect description of his demented performance in "The Mask," for my money the most purely delightful of his roles. A friend of mine once described Carrey as the black, gay comic who isn't black or gay, and this paradoxical statement may capture some of the distinctive edge below his cheerful exterior.

Actually, nobody could be whiter than this goofy, gangly guy from Newmarket, Ontario, and you might argue that Carrey's association with African-American culture is largely accidental. He got to know Damon Wayans when both had small parts in "Earth Girls Are Easy" in 1989 (as Furry Aliens No. 2 and No. 3), and wound up as the only white male in the cast of "In Living Color." On one hand, Carrey's lantern-jawed "Father Knows Best" face was perfect in skits that parodied whiteness; on the other he had the slinky spine, dangerous dance moves and gift for mimicry that allowed him to get down.

Carrey's desire to provoke and exploit sexual discomfort, on the other hand, is an integral part of his comic style. He's been accused of homophobia -- mostly for the hilariously overplayed "Crying Game" parody in "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective" -- and become the object of whispers about his own sexuality, which is probably just the combination he's looking for. (For what it's worth, Carrey's extensive trail of ex-wives and ex-lovers in Hollywood suggests that he's an incurable hetero.)

From the ass-ogling Lloyd Christmas of "Dumb & Dumber" to the queeny Riddler of "Batman Forever," Carrey's characters have often been sexually ambiguous, a trend that culminated in his borderline-homoerotic stalker role as Chip Douglas in "The Cable Guy." Although that film has become something of a cult object on video (as well it should), the initial audience antipathy toward Carrey's portrayal of a disturbed and needy loner seems to have scared him off this particular theme. His characters in "Liar Liar" and "The Truman Show" are Pat Boone-straight, and, quite frankly, are weaker as a result. Whatever psychological explanation you want to propose for it, Carrey's best work is lightly dusted with queerness. ("Man on the Moon" is a special case in this regard -- Kaufman's alien weirdness had nothing to do with sexuality.)

In addition to offering him a major career break, Damon Wayans also identified something crucial that lies just below the surface of Carrey's mock-debonair clowning. "Damon came backstage after I did something really weird," Carrey told Playboy in 1994, "and said, 'Hey, man, you are one of the angriest people that I have ever seen.'"

It may be pointless to play amateur shrink with celebrities one has never met, but in Carrey's case it's irresistible. Although he no longer discusses his childhood in interviews, he has said that after dropping out of high school at 15 (to go to work after his father was fired), he briefly became a vandal and a bigot. One of his former teachers told People in 1996 that Carrey was constantly the butt of ridicule because of his family's poverty, adding, "He'd put together these funny routines to make the kids laugh so he'd be accepted."

When he wasn't obsessively rehearsing Jerry Lewis or Dick Van Dyke routines in the mirror, the teenage Carrey worked as a janitor in a tire-rim factory. Some of his now-famous physical impressions, like his impersonations of Flipper or a praying mantis, grew out of entertaining his mother while she was in bed with kidney disease. In the same Playboy interview, one of his most revealing, he admitted, "My focus is to forget the pain of life. Forget the pain, mock the pain, reduce it."

As his career has matured, Carrey has learned to conceal his anger and pain behind the persona of a self-confident doofus who, as Carrey has said of Ace Ventura, "is totally full of shit" but "sexy as hell in his own head." Those who saw Carrey do stand-up in his early years in Toronto and Los Angeles (where he moved at 19) remember a brilliant but undisciplined performer who often refused to let go of a gag. He'd wriggle around on the floor as an armless and legless character called the Worm Boy, for example, long past the point when the audience was tired of it.

On "In Living Color," he began to channel his limitless energy into characters like Fire Marshal Bill, a ghoulishly scarred figure whose household safety tips always led to catastrophe. Bill seems like the abusive dad of Carrey's sweeter but equally clueless later characters, from Ace Ventura to Lloyd Christmas and Stanley Ipkiss in "The Mask." All of Carrey's pre-"Cable Guy" characters, in fact, are lovable losers who survive adversity, probably the most fundamental archetype of American comedy. They're clearly in the same tradition as Chaplin's Little Tramp, Lewis' grown-up 9-year-old and Woody Allen's neurotic schlemiel.

Like any great comedian, Carrey himself is the attraction, not the character he plays. In his early films, he reminds me of the Marx Brothers -- all three or four of them rolled into one (minus Groucho's acerbic sarcasm). Their best movies were nothing more than outlandish premises to get the shtick rolling -- what if Groucho were president of an entire country? -- and exotic settings for them to riff against. No one who watched "Ace Ventura" gave a crap about the missing dolphin; the point of the film is, in director Tom Shadyac's words, to go "way off planet Earth."

When Carrey descends into the empty dolphin tank and throws himself into a rapid-fire series of "Star Trek" impressions, there's absolutely no reason for it, except that the echo sounds really cool. As for the infamous "Can I ass you a few questions?" routine, which Siskel and Ebert felt signaled the death of Western civilization, sure it's moronic. But I defy you not to laugh at the sheer brazen I'm-high-on-life stupid brilliance of it. As Carrey told an Us magazine reporter in 1994, "Until 'Ace Ventura,' no actor had considered talking through his ass."

Whether whining like an injured hyena in "Dumb & Dumber" ("Want to hear the most irritating sound in the world?") or whirling through the vertiginous, improvised dance numbers of "The Mask," where he goes from Jimmy Stewart to Desi Arnaz to Miss Piggy within a few seconds, Carrey conveys the sense that he's a live-action Bugs Bunny, a surrealist who's safe around children. You can't blame him for wanting to escape from this niche, but Carrey in his most free-flowing, pure-id moments may come the closest to Andy Kaufman (who, after all, once took an entire Carnegie Hall audience out for milk and cookies).

As for "The Cable Guy," let's just say that if it had cost $40,000 and been made by NYU students, instead of costing Columbia Pictures $40 million (half of it Carrey's salary), critics would still be talking about it as one of the decade's surprise masterpieces. Carrey and director Ben Stiller transformed the goofball persona millions of viewers had grown to love into someone deviant and sinister -- Chip Douglas is another loser who thinks he knows what he's doing, but he wants to take over your life and invade every inch of your personal space. Besides, in its own twisted way, it's absolutely hilarious; Carrey's karaoke version of the Jefferson Airplane's "Somebody to Love" may be the sickest, weirdest, most Kaufmanesque thing he's ever done.

When journalist Ron Rosenbaum, one of the high priests of the Kaufman cult, saw Carrey impersonate Kaufman's Conga Guy character at a 1997 Hollywood party -- before Carrey had even gotten the "Man on the Moon" part -- he was struck by the uncanny connection between the two. "Whether or not haunted congas possessed him," Rosenbaum wrote in Esquire, "for one brief midnight moment of conga madness, Jim Carrey was Andy Kaufman, capturing something essential about Andy: the preoccupation with the dangerous, self-intoxicating madness of the performing self at its most ecstatic."

I'm worried that the likely success of "Man on the Moon" will make Carrey and his army of agents and managers draw precisely the wrong conclusions -- instead of understanding that Carrey's success depends on "the performing self at its most ecstatic," they'll decide that now he has to be an Actor. There's no question that Carrey can act; he controls his emotions almost as readily as his Gumby-like physique. But those who celebrated Carrey's "real" acting in "The Truman Show," it seems to me, are hewing to a totally inappropriate standard. Why is it morally superior to play one consistent character all the way through a film, rather than the dozens of fragmentary personas Carrey adopts and casts off in "Ace Ventura" or "The Mask"? He's a showman -- don't we want to see him put on his best show?

Mind you, if Carrey really wants to experiment with difficult dramatic roles, I say more power to him. He purportedly did a fine job as a young alcoholic in the 1992 TV movie "Doing Time on Maple Drive" (which isn't available on video). I bet he could play the anguished young men of modern drama brilliantly -- say, Biff in "Death of a Salesman," Brick in "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof" or Edmund in "Long Day's Journey Into Night." But there are other people who can do those roles, and anyway they lead actors down a slippery slope into a dreary Hanks/Williams future of understanding shrinks, conscientious cops, inner-city schoolteachers and heroic dying husbands.

So far Carrey has resisted this path. His next film is "Me, Myself and Irene," a Farrelly brothers comedy in which he plays a character with a split personality. In the holiday season of 2000, he'll star as the green antihero of Ron Howard's "The Grinch Who Stole Christmas," surely a role Carrey was born to play. There's been talk of remaking Don Knotts' "The Incredible Mr. Limpet," in which a man turns into a fish.

Animals, monsters and guys with unlikely psychiatric conditions -- this is absolutely the terrain where Jim Carrey is going to find his greatest freedom. He isn't Andy Kaufman and he never will be, but the gift he has is no less rare and wonderful, and it shouldn't be wasted in "quality" films. If Kaufman visits Carrey at night, I hope he tells him to let lesser mortals play hefty garbagemen who save drowning toddlers; Jim's mission is to root through the trash and celebrate what he finds there. Then Andy quits talking out his ass, stands up and slowly melts away into the night.

Shares