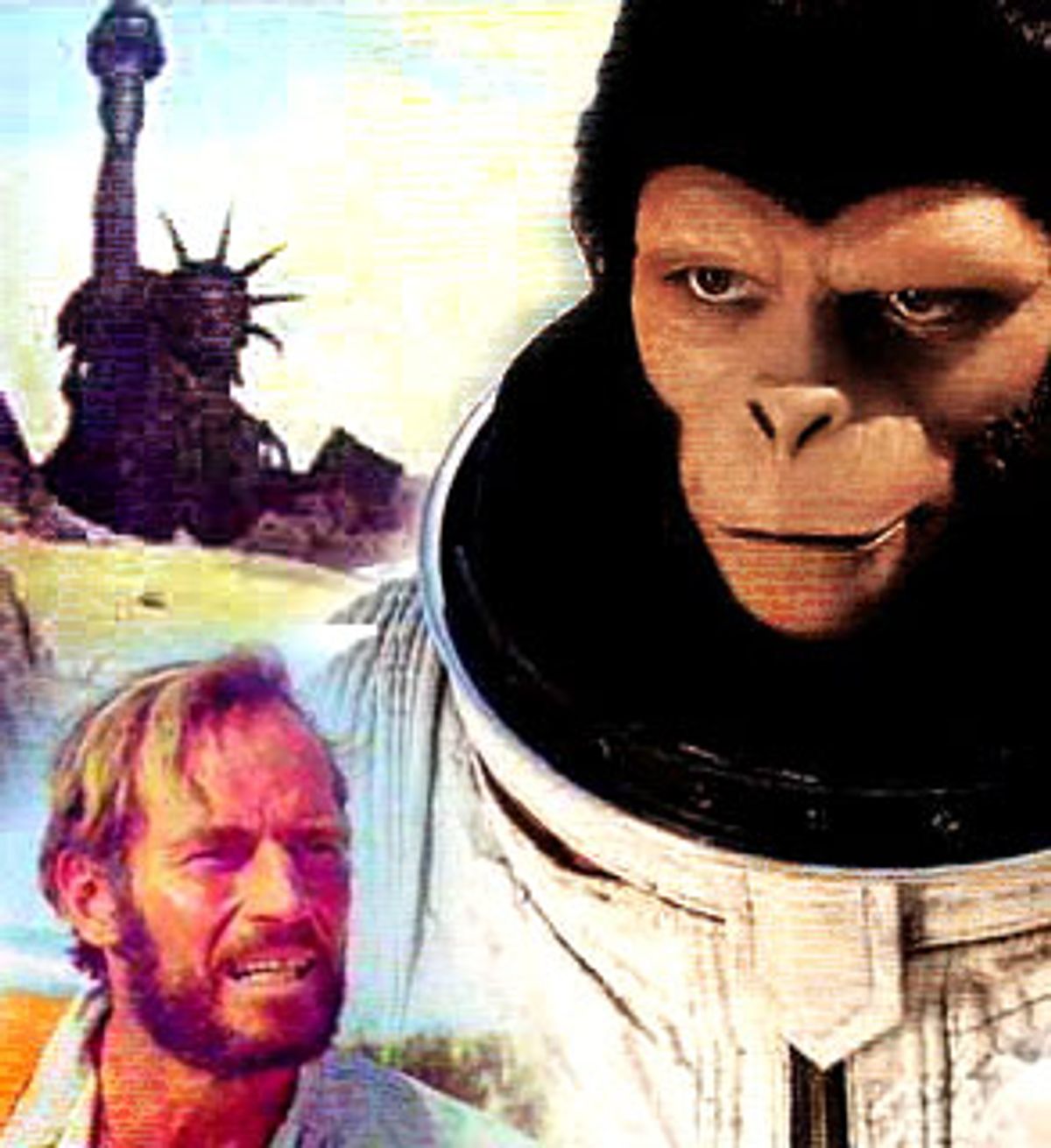

In 1968 "Planet of the Apes" branded the ass of cinematic history with its final image: Charlton Heston, playing the film's misanthropic but resourceful human from the past, stumbles down a beach and comes upon the Statue of Liberty buried up to her neck. Heston suddenly comprehends the enormity of his situation: The Planet of the Apes is actually Earth!

The apes had taken over after the humans wiped out civilization with nuclear weapons. "Damn you! Damn you all to hell," shouts Heston, his misanthropy resoundingly justified.

The political message is ham-fisted but crystal clear: A nuclear holocaust will ruin us all. And then apes will take over the planet. Or something.

"Planet of the Apes," despite a couple of iconic images like that final scene, is a dreadful film, a compendium of clumsy dialogue, one-dimensional characters, risible plot turns and long silences broken by incomprehensible meaningful looks. But it has stayed with us because in conception, if not execution, the film had something to say.

This was before PETA became a household word, before things like animal experimentation controversies could muddle the film's message, which might be the case with Tim Burton's new edition. The original film's metaphor, in those civil rights-riven times, was plain: How would whites like to be treated the same way they treated blacks? Black leaders never really got behind the film, perhaps because, however bad the African-American condition was at the time, they did not feel that a comparison to apes was particularly helpful to their cause.

Ah, the '60s.

The first film and its four successors through 1973 explored other social issues as well, including slavery, religion, veganism, interspecies smooching, genocide as sport and even animal experimentation. In the late '60s, entertainment often came with a message, but "Planet of the Apes" looked for a different audience. The stuffed shirts got "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner," Stanley Kramer's all-star look at an interracial marriage.

Everyone else had "Planet of the Apes."

America at the time was awash in social upheaval, controversy, internal struggles and war. American soldiers were being slaughtered for unclear reasons far across the sea. Antiwar sentiment was churning. Race riots ripped the country's underbelly, and our political and civil rights leaders were being assassinated.

Elsewhere, things weren't much better. U.S. Green Beret-trained Bolivian soldiers had executed Che Guevara in 1967. That same year, U.S. planes were bombing Hanoi, and Israelis and Palestinians were at war over the Sinai Peninsula. Concurrently, NASA had suspended all manned space flights after the deaths of three astronauts, who burned to death in a launchpad fire. "Planet of the Apes" also became the methadone treatment for NASA junkies after a fix.

While the films addressed a variety of social issues, they certainly didn't try to solve or address them all. And there were huge blind spots. When the original appeared, feminists were appalled that Nova, Heston's mate, was mute and subjugated. In the second film, "Beneath the Planet of the Apes," Don Pedro Colley was cast as a character called "Negro." (Some blame the writer of "Beneath" for that one, but the stumble was more likely endemic in Hollywood: Colley went on to star in "The Legend of Nigger Charley" in 1972 and "Black Caesar" in 1973.)

Still, more often than not, in the "Planet of the Apes" movies social issues were made anthropomorphic and in your face. Lead characters died. Shit hit fans. People made mistakes. Worlds blew up. What follows is a brief survey of plots and messages from the five original films, from the horrors of nuclear holocaust to talking monkeys to the golden rule: "Ape shall not kill ape."

"Planet of the Apes" (1968)

Charlton Heston starred as Taylor, a sardonic astronaut who crash-lands on a futuristic Earth populated by apes and the primitive humans they love to hate. Taylor's buddies are killed, stuffed and used for scientific experimentation. Taylor befriends two chimpanzee doctors, Cornelius and Zira, and escapes into the Forbidden Zone to find his fate. The film had a $5.8 million budget and brought in $26 million at the box office, an enormous amount at the time.

"Beneath the Planet of the Apes" (1970)

Cornelius and Zira save astronaut Brent (James Franciscus). He follows Taylor's trail to a subterranean lair of nuclear-bomb-worshiping mutant humans who would rather blow up the world than allow apes to see their icky, vein-bulging mutant heads. The mutants love their bomb, and prepare to use it to destroy the ape population, but first they sing a lovely hymn to it in a cathedral located in a decimated New York subway. When the apes arrive to put a stop to the plan, they knock over the warhead, ignorant of its potential. Soon after his beloved slave/mate, Nova, is killed, it is Taylor who sets off the trigger that destroys the world, not the mutants or the apes.

"Escape From the Planet of the Apes" (1971)

The film opens with a sea landing of three "apestronauts," who arrive in the spaceship Brent (Franciscus) left behind in the future, and come to modern-day Earth. "Escape," written by Paul Dehn (who wrote all of the '70s "Apes" sequels), is the worst offering of the series, yet also its most memorable. Cornelius and Zira somehow escaped from the future (the one in which Taylor destroyed the Earth) and return to the present, much to the surprise of everyone. The talking apes become instant celebrities, are wined and dined, are taken on shopping trips and dress in colorful 1970s polyester fashions.

The two celebrity apes become victims in a presidential plot to save mankind, and are killed by Dr. Otto Hasslein (Eric Braeden), who is fearful of a future ruled by apes. Plenty of TV character actors appear in this one, including Bradford Dillman, William Windom and Sal Mineo. Cornelius and Zira hide their baby in Ricardo Montalban's circus, and it is saved from execution.

"Conquest of the Planet of the Apes" (1972)

Billed as "The Revolution!" "Conquest" has Cornelius and Zira's grown son, Caesar (who was hidden in the circus for 20 years), rise up against the tyranny of mankind, where apes have become slaves and suffer stinging epithets such as "DO!" and "NO!" Caesar liberates the apes from bondage after leading a violent revolt against the powers that be. His first order of business is to enslave the slave masters so that everyone can get along peacefully. Slaves enslaving slave masters -- what a concept! They get what they deserve.

"Battle for the Planet of the Apes" (1973)

In "Battle," which takes place 12 years after Caesar's revolt, king of TV character actors (and Hollywood country bumpkin) Claude Akins plays one hell of a mean gorilla general, Aldo. He's sick of Caesar and his stupid post-apocalypse rules of order, especially the ones where he doesn't get to shoot a bunch of humans. In this, the last big-screen "Apes" feature of the original series (a television series and a cartoon would follow), not only does Aldo want mutant humans and friendly slave humans eliminated (read: genocide), he also kills Caesar's son, Cornelius, and plots to kill Caesar too! Kind of like tapping into the assassinations of Malcolm X, a pair of Kennedys and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. all in one. One-stop shopping at the assassination metaphor market!

The film starts with Aldo in writing class with a bunch of children and a few other "slow" gorillas. Aldo botches a writing assignment, and his human teacher teases him. Aldo gets all fired up and rips up another kid's assignment, to which the teacher yells "NO!" Well, that starts a classroom riot, because written right there in the ape lawbooks is that the word "NO" can never come from a stinkin' human's mouth and point in the general direction of an ape. For some reason this human "slave" has never heard of such a thing, because everyone has to explain it to him. What rock has he been under? He's a slave! And he never heard of that law? Humans are stupid animals. In the teacher's defense, an orangutan (played by a very apelike Paul Williams) named Virgil (the Einstein of the group) explains to Caesar that the teacher "uttered a negative imperative." Sounds like the N-word to me.

This film has it all. Human against ape, mutant against human, mutant against ape and even (cringe) ape against ape. Cornelius, Caesar's little son, stumbles upon General Aldo, who tries to persuade his fellow gorillas that they all need to get ahold of guns, get rid of Caesar and start killing humans. When Aldo discovers Cornelius listening in from above, he takes his sword and hacks off a tree limb the lad is clinging to. Cornelius falls to his death. (Ape kills ape, a big no-no.)

When the dust settles, the mutants are dead, and apes and humans live in peace, but not forever. The final scene in "Battle for the Planet of the Apes" shows caramel-voiced orangutan lawgiver John Huston, preaching peaceful get-along dogma to a gathering of ape and human children. They gather around a statue of their long-dead leader Caesar, near a serene mountain pool. At the end of the moralistic sermon, a young black human girl shoves a chimp boy, and he shoves her back. Caesar's statue cries like a forgotten Christ. It's a tragedy!

The strangest thing about the films is that while all of the allegories are as obvious as a cudgel, the theme that carries across all the movies is much darker. Co-written by Rod Serling, the original "Planet of the Apes" screenplay echoed the nihilistic antihero/anti-solution Serling used so well in his "no hope scenario" television series, "The Twilight Zone." All the films had a bummer downside. Each ended horribly. There was little hope for salvation.

But in a way, that was the appeal. They movies were, in essence, American tragedies. The "Apes" films held up a carnival mirror to American society. The result was a cross-eyed, camped-up metaphorical mess, but it managed to please the public.

Why? Because frankly, Americans felt they deserved the spanking. We were no longer a nation of sheep, but a nation of cynical sheep who collectively believed things were in bad shape. We had only ourselves to blame.

Shares