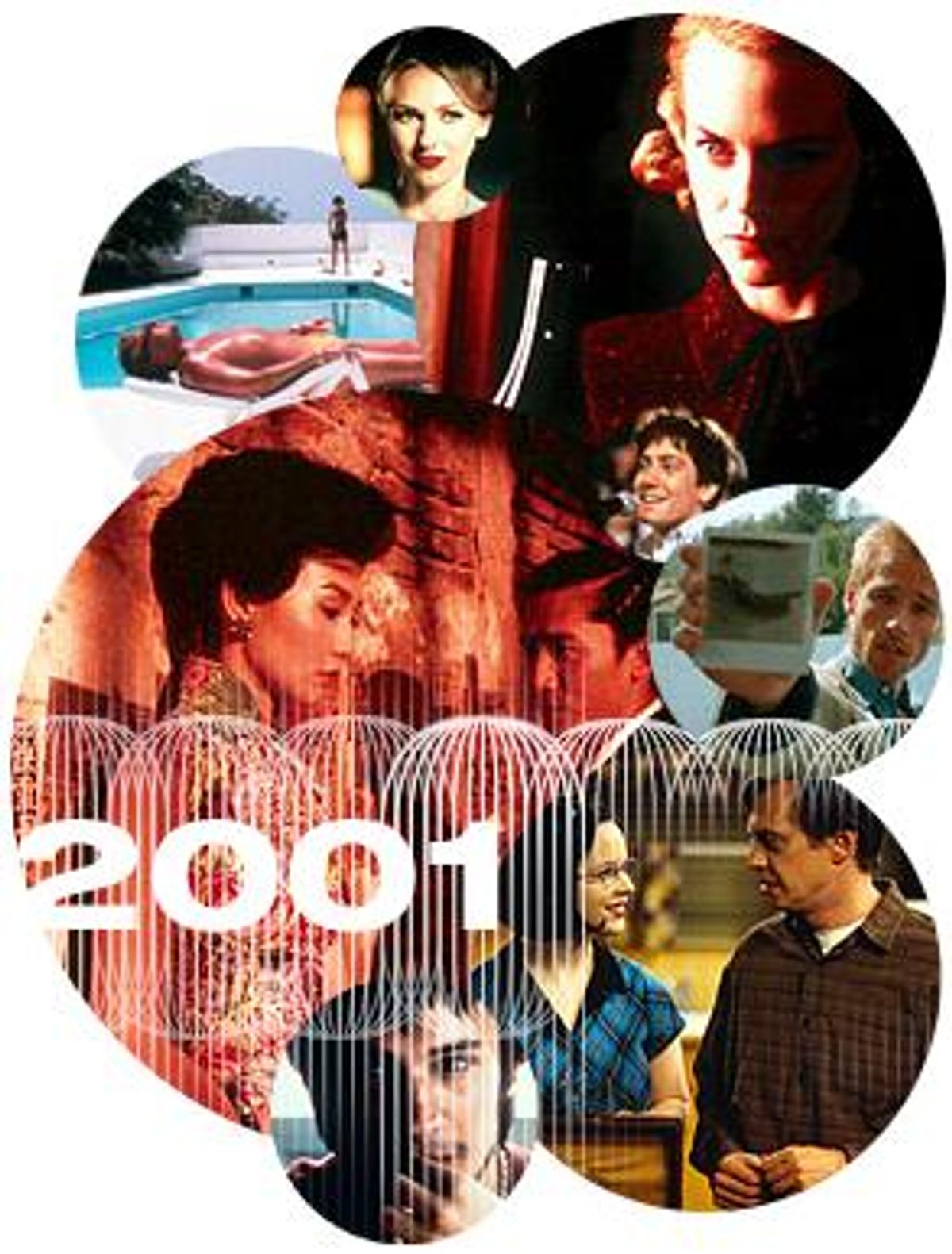

It has to be a good year for something, right? I mean, something besides therapists and manufacturers of latex gloves. In fact, as attentive filmgoers are starting to notice, 2001 has already become one of the best years for truly strange movies in the last few decades. I'm not so much talking about movies that offer an escape from reality (as much as we all might appreciate that right about now) but those that present almost hallucinatory alternate realities, or those that suggest nothing could be weirder than reality itself.

Hollywood had a dismal summer in which most of its big-budget offerings, with the sole exception of "Shrek," opened huge and then went down like the USS Arizona. That's a joke that might have been funny a few months ago; and indeed, the events of Sept. 11 made everyone in the mainstream film world feel justifiably uncomfortable, if only for a while. The real disasters we saw on that day brought the most callous excesses of the blockbuster era into horrific reality. They made those excesses seem puny, which is why perhaps no burst of patriotism these recent weeks manifested itself in a desire to see "Pearl Harbor" again.

And, of course, box office isn't the point: None of those big-budget movies are memorable or represent good filmmaking. Yet while we were all watching interestedly as the hype around "Pearl Harbor" produced a delicious flop, out there on the margins of the moviemaking system, both in the U.S. and around the world, exciting things were happening.

This goes against everything that film critics, myself included, are accustomed to saying. We have a certain Chicken Little tendency: The sky is always falling, the movies get crappier and crappier every year, and the golden age that never existed in the first place is fading ever more into memory. Soon the entire entertainment universe will be ruled by one gargantuan Spielberg-Lucas-Cameron machine, squatting astride the globe and grinding out treacly sentiment and sadistic cruelty in roughly equal portions.

There may be a kind of truth to this view, which has been around at least as long as Pauline Kael's influential 1980 essay "Why Are Movies So Bad?" if not since time immemorial. But it's not the kind of truth that's, well, actually true. Sure, the Hollywood production system tends to create shallow, cynical and sloppy movies. But guess what? It always did.

When we think of Hollywood in the 1940s, we think about "Casablanca" and "The Big Sleep" and Lauren Bacall saying, "You know how to whistle, don't you? Just pucker up and blow." We don't think about Ronald Reagan and Shirley Temple (as a couple!) in "That Hagen Girl" or about "A Guy Named Joe," directed by Victor Fleming (who helmed both "The Wizard of Oz" and "Gone With the Wind"), the slogan for which was "A guy -- a gal -- a pal -- It's swell!" But the latter kind of movie, as always, outweighed the former by perhaps 10 to 1.

Yeah, good mass-culture popcorn movies got made in the old Hollywood, and they still do in the new one, even though you wouldn't know it from the evidence of 2001. What this year, and indeed the last several years, have brought us is something far more surprising: a new golden age of art movies. Yeah, that's what I said, and I'm not taking it back.

We told ourselves that American independent film had died, or morphed into an inflated and corrupt imitation of itself, and then 1999 brought us "American Beauty," "Being John Malkovich" and "Three Kings." We thought foreign filmmakers had enslaved themselves to making pallid, pretty imitations of Hollywood spectacle, and then 2000 brought us the uncompromising visions of Abbas Kiarostami ("The Wind Will Carry Us"), Edward Yang ("Yi-Yi"), Bruno Dumont ("Humanité") and of course Ang Lee ("Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon").

What I'm describing isn't quite old-school art film, with its embittered ideological opposition to Hollywood's aesthetics and methods; as the case of Steven Soderbergh has demonstrated, Hollywood's borders aren't what they used to be. Some of these filmmakers, like Lee or David O. Russell ("Three Kings") have at least one foot in the Hollywood system, while others, like Kiarostami or Dumont, belong almost exclusively to the cinephile world of film festivals, art museums and eccentric big-city video stores. (Be still my heart!)

After the indie resurgence of '99 and the foreign gems of 2000, this year has turned out to be an embarrassment of riches, to the total surprise of almost everyone. I suspect that most critics (again, not excepting myself) have become so conditioned to the idea that art cinema is dead and that reaching a mass audience is the only acceptable goal that we haven't quite noticed how amazing 2001 has been so far.

We've seen remarkable debuts, films from rising (if eccentric) stars and unexpected sleight-of-hand from established masters. We've seen ghost stories, love stories, tales of crime and fables about the pain of growing up. We've seen stories that twist time to their own purposes, that collapse history and geography, that tiptoe into the murky realms where reality, fantasy and psychosis come together. We've seen rapturous movie-movies in love with the world of the screen and works that create a highly disciplined illusion of reality. Most of all, we've seen highly individual films made by people who assume a community of viewers smart enough and open-minded enough to ride along on their idiosyncratic journeys.

In other words, we've seen art movies. If you want to resist the term, I sympathize. You think it makes you a snob, an elitist, someone who can't appreciate the juvenile catharsis of fucking and explosions (but mostly just explosions) provided by Hollywood films. Well, relax. These are art movies that speak the language of pop and understand its sensibility. Their visual and narrative daring go hand in hand with an appreciation of fashion and rock and roll, with humor, terror and violence. Their beauty and passion are not primarily intellectual; they don't depend on your knowledge of Schubert or Tintoretto. We're not talking obscure Continental angst or Maoist monologues here. Anyway, it's the only term I can think of that covers the range of adventurous visions that seem to be blossoming around us.

So unbutton your inner elitist, pour yourself an espresso and enjoy. Weird is back, perhaps more than at any time since the 1970s (and I couldn't be happier about it). Maybe new technologies in filmmaking have something to do with this, although that whole argument is so boring I refuse to take it seriously. Maybe it's part of the resistance to global corporate capitalism, and its creeping campaign to erase all difference and individuality everywhere from Vancouver to Singapore. (Operations in the Middle East are on hold for the time being.) Maybe the intellectual, emotional and financial bankruptcy of Hollywood has opened the minds of filmmakers, distributors and viewers alike. Maybe it's just one of those cultural currents or viral memes that can't be explained.

Entirely discounting Hollywood's abysmal summer (and what should be a boffo, Frodo-fueled holiday season), here are my personal selections from the best weird-movie year I can remember. Many worthy contenders were left out for a variety of reasons; when you've exhausted this list, consider such slightly less weird but highly honorable also-rans as "Signs and Wonders," "Ginger Snaps," "The Anniversary Party," "Under the Sand," "Eureka," "The King Is Alive," "The Deep End," "Rape Me," "The Princess and the Warrior," "Hedwig & the Angry Inch," "Lisa Picard Is Famous," "Our Lady of the Assassins," "Haiku Tunnel," "Fat Girl" and "Va Savoir."

OK, so the gimmicky neo-noir is not my favorite genre, but this diabolical puzzler is about as good as it gets. At first, Guy Pearce's canny star performance seems flat and forced, until you realize that Leonard, the half-amnesiac protagonist, is himself an actor; he remembers who he used to be but has no idea who he is now. It is only the beginning of this film's dazzling construction that writer-director Christopher Nolan tells the story in reverse order, each scene ending where the previous one began. So we begin to see the origins of the desperate clues Leonard leaves for himself in his "investigation" of his wife's murder -- notes, scribbled-on Polaroids, a series of elaborate tattoos -- and to understand that the main manipulator of his disorder may be Leonard himself. Like most noirs, this is a heartless essay in paranoia and cruelty; like the best of them, its precision, its lustrous imagery and its devious tale of love and madness will get under your skin and crawl around like parasites.

This astonishing debut feature from Alejandro González Iñárritu, a former Mexico City rock DJ, combines the vicious energy of Quentin Tarantino, the vivid surrealism of Luis Buñuel and the moral melodramas of Mexican telenovelas in an unforgettable panorama of our continent's largest city. Three stories of love and betrayal, which connect the worlds of the poor, the middle class and the privileged, intersect by way of a hideous car accident and a loyal but murderous dog named Cofi. "Amores Perros" became notorious for its simulated but highly convincing dogfight scenes, but the film's real subject is the emotional violence the director sees underlying all of life in Mexico's gorgeous and terrifying capital. It's a great film, if not an easy one to take, and it serves to remind Americans how little we really know about the diverse and complicated nation on our southern border.

In the Mood for Love

I have strongly mixed feelings about Wong Kar-wai, the artiest of major Hong Kong filmmakers. (His "Chungking Express" is one of my favorite movies, but I found "Fallen Angels" murky and distasteful and "Happy Together" a beautiful snoozefest.) But there's no disputing his talent or the uniqueness of his vision, and "In the Mood for Love," a lustrous period romance set in early-1960s Hong Kong, has finally brought him a wider Western audience. Tony Leung Chiu-wai and Maggie Cheung play neighbors whose discovery that their spouses are having an affair thrusts them into an unexpected intimacy. Wong may well go back to his customary frenzied visual experimentation the next time he tackles contemporary subject matter, but this supernally modulated (and profoundly sad) composition of lights, shadows, colors and fabrics speaks to his tremendous aesthetic flexibility as well as his constant theme of loneliness.

For his first dramatic film, high-priced English commercial director Jonathan Glazer turned to playwrights Louis Mellis and David Scinto, resulting in a crime thriller that looks like MTV, sounds like Harold Pinter and revives the bloody-minded existentialism of the best British flicks of the '60s. For all Glazer's dazzling shotmaking and supersaturated Costa del Sol colors -- and even the memorable performance of Ben Kingsley as an East End crime boss -- the film's heart lies in Gal (Ray Winstone), a flabby, retired gangster who loves his ex-porn-star wife (Amanda Redman) more than life itself. In the neo-noir sweepstakes, "Sexy Beast" may not have the narrative invention or clockwork mechanics of "Memento," but it has just as much visual flash, better line-by-line dialogue and more human warmth.

Some critics with advanced allergies to ironic storytelling understood "Ghost World," the dramatic debut of "Crumb" director Terry Zwigoff, as yet another snarky hipster attack on Middle America. If anything, this tale of the awkward life-zone after high school, based on the comic books by Dan Clowes, is a satire with at least as much to say about the self-fulfilling nihilism of hipster culture as about the mainstream. (Yes, the attack on lame Caucasian blues bands and those who love them is utterly gratuitous -- and very funny.) Enid (the remarkable Thora Birch from "American Beauty"), a wannabe artist who dresses like a 1977 punk, begins to drift away from her best friend Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson) and into an awkward relationship with a 40-ish record collector named Seymour (Steve Buscemi), who is easily the most compelling portrait of an emotionally stunted, middle-aged subculturite ever set on celluloid. The result is a finely nuanced, wonderfully acted and finally heartbreaking study of cultural exile.

The Others

Not an work of innovation so much as a reclamation project, Alejandro Amenábar's "The Others" marks a return to the finest traditions of supernatural film, in which the principal special effects (and often the only ones) are script, characters, atmosphere and editing. A Gothic classic set in a grand and isolated house in the British Channel Islands, "The Others" follows the increasingly neurotic Grace (Nicole Kidman) in her efforts to protect her photosensitive, hypersensitive children from whoever or whatever is haunting them. Like Robert Wise's 1963 "The Haunting" or Jack Clayton's 1961 "The Innocents" (an adaptation of Henry James' "The Turn of the Screw," clearly an influence here), "The Others" is a tale of sexual repression and the evils it can produce. Kidman's daring and masterful performance is matched by Fionnula Flanagan as the leader of a trio of mysterious servants who show up on the estate and clearly know more about "the others" inhabiting Grace's house than they let on.

More has already been written about this film in this publication than about any other cultural product of the past decade; if nothing else, "Mulholland Drive" makes it clear that David Lynch has returned from near-irrelevance to the center of the movie world. As ever, Lynch's tale of switched identities, mysterious entities, unexplained apparitions and erotic hijinks risks seeming incomprehensible or ridiculous. But unlike his hallucinatory 1997 "Lost Highway," which came apart at the seams and proved impossible to reassemble, "Mulholland Drive" has an undeniable thematic and emotional coherence. For what it's worth, unlike my esteemed colleagues Bill Wyman, Max Garrone and Andy Klein, I see the film's dreamlike first two hours as just as "real" as its drearier concluding scenes. To impose a single interpretation on Lynch is fundamentally to miss the point of his movies. You can justifiably call him a postmodernist, a deconstructionist or any other five-dollar name you like, but for him the movie screen is a state of rapture, a sacred and serious space where all kinds of magic become possible, where truth and lies, reality and illusion, are intermixed and indeterminate. Of course, it's also a place where he can display an abundance of naked pseudo-noir babes getting it on and convince us that it's art.

Hampered by an unhelpful title and unsympathetic reviews from mainstream critics, this soaringly ambitious debut from writer-director Richard Kelly has so far failed to find the wide audience it deserves. So I'm instructing you now not to miss this hallucinogenic fable of teenage mental illness, time travel and/or doomed love, all set to hits by Tears for Fears and Echo and the Bunnymen. Kelly's sweeping, tragicomic vision of American family life circa 1988 clearly belongs alongside such second-wave indie directors as Darren Aronofsky ("Pi," "Requiem for a Dream") and Wes Anderson ("Rushmore"). But he also has one foot in the bittersweet-candy universe of John Hughes' '80s teen-romance classics and the "Back to the Future" films; maybe teenagers thought this was an art film and grownups thought it was a teen adventure. They were both right. As with "Mulholland Drive," questions of fantasy vs. reality seem beside the point here. Is titular teen Darko (Jake Gyllenhaal) simply losing his mind, or can he really bend time and space with the help of the sinister rabbit-demon who visits him at night? Answer that however you like, but Kelly's passion -- for life and for the movies -- resonates through every scene of "Donnie Darko," whatever its flaws.

Shares