We've all had a long time -- since 1932, when she made her first movie, "A Bill of Divorcement" -- to get used to Katharine Hepburn, or, rather, to get used to the idea of Katharine Hepburn. But the actress and the idea are two different things. It's easy to hit the highlights of her body of film work -- 1938's "Bringing Up Baby," 1951's "The African Queen," the pictures she made with Spencer Tracy from the late '40s through the '60s -- and use them to robotically reaffirm her place as an icon.

But the trouble with icons, figureheads that we've cut down to manageable size with our well-meaning adulation and respect, is that they're by their very nature boring. And Hepburn, who died on Sunday at age 96, has always been anything but boring. Crisp and strange, her line readings were always attuned to her own specially calibrated inner clock -- no actor, either among her contemporaries or her heirs, would dare imitate it, simply because there's no way to pull it off. Her rhythms have always belonged solely to her, and it took audiences many years to fully adapt to them.

Looking at Hepburn's work from the '30s, maybe even especially those movies that she made (circa 1938) when she was so infamously labeled "box office poison," it's not so hard to imagine why she must have seemed odd to audiences. She was "poison," pure and simple, because she didn't ingratiate herself with moviegoers. She demanded that they come to her -- but once they did, once they took the at first awkward step of readjusting their inner clocks to move with hers, they became privy to performances that rank among the most original, and the most purely affecting, of American movies: The young Hepburn gave us true, unvarnished emotion with every drop of sentimentality dried out of it.

As George Cukor, who directed Hepburn in her first picture, as well as in, among others, "Holiday" (1938) and "The Philadelphia Story" (1940), told Gavin Lambert: "She was never a 'love me, I'm a lovable little girl' kind of actress. She always challenged the audience, and that wasn't the fashion in those days. On the hoof, when people first saw her, they felt something arrogant in her playing. Later, by sheer feeling and skill, she bent them to her will. Of course, her quality of not asking for pity, not caring whether people liked her or not, was ideal for 'The Philadelphia Story.'"

Hepburn, particularly in those '30s performances, often came off a little mannered. And yet you couldn't call her stiff. In the 1935 "Alice Adams," adapted from the Booth Tarkington novel, Hepburn plays a young woman who yearns to break out of her lower-middle-class home life and sees the young, handsome and rich Fred MacMurray as her ticket out. But she isn't your typical social climber. She and MacMurray play their parts so you can see the flickers of connection, unbelievable as you think they'd be, between them; their characters genuinely seem to like each other.

But the controlled, manicured rawness of Hepburn's performance is the key to "Alice Adams." Striving to impress MacMurray, she natters enthusiastically and much too brightly; too desperate to simply be herself, she adopts the kinds of airs that she believes characterize rich people. Her pretense is a kind of mania that electrifies her from within. And yet, even wired with all that falseness, Hepburn's Alice is more real, and far more alive, than the cool, stuffed-bird rich girl MacMurray is supposed to be interested in. Just three years into her movie career -- she had begun on the stage, and would return there now and then throughout her career -- Hepburn knew how to give a performance that was both sociologically savvy in its understanding of the ways we all yearn for things we can't have (a theme that would have had even more resonance during the Depression) and in its piercing humanity (we like to think of humanity as warm, but it's just as often sharp). Hepburn's Alice is a performance that's both hard to like and impossible not to fall in love with.

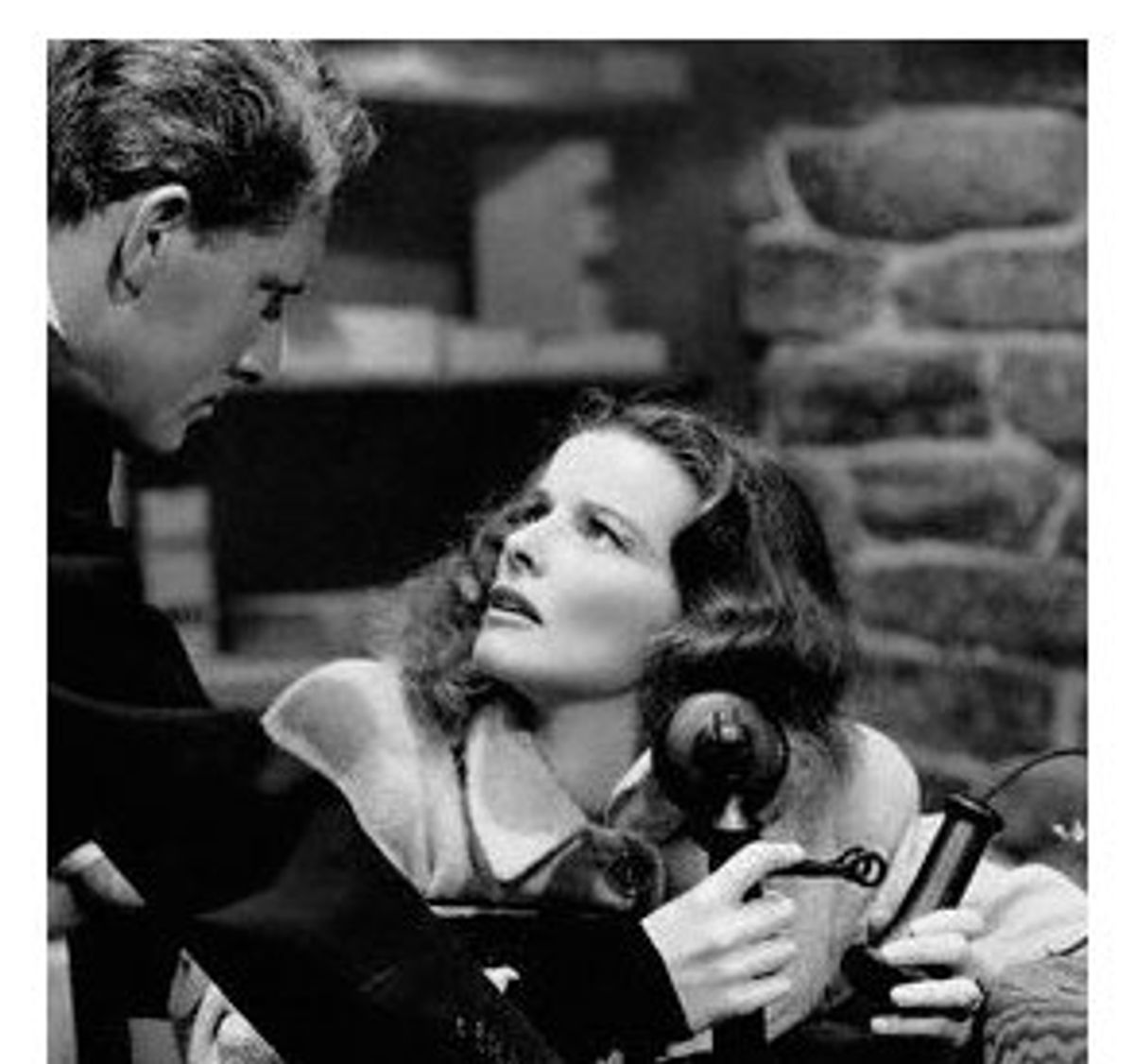

Nearly all the Hepburn tributes and appreciations that are beginning to appear refer to her "patrician" good looks, and there's no better word to describe them: Her figure, even as she aged, was reedy and athletic; she carried herself like a compass arrow continually pointed north; her cheekbones looked as if they'd been chiseled from the same timber as the Mayflower, and you'd have thought those narrow, resolute lips were made just for shaping wisecracks, not for kissing. But Hepburn could play romantic, easily and beautifully, simply because her classy veneer was never at odds with her vulnerability. That was her art: She never questioned that flinty intelligence and cautious tenderness couldn't coexist.

In one of my favorite Hepburn performances, in Cukor's "Holiday," she played a rich girl who yearned for the kinds of riches that lay well outside the conscription of her social class; she found them in the bookish, funny and free Cary Grant. As with her performance in "Alice Adams," Hepburn played the role so we'd understand that money wasn't really the issue at all -- it was the act of pure wanting, the drive to become the person your surroundings won't allow you to be. Hepburn's warmth as a performer flourished because of her coolness, not in spite of it. She may have been a pale hothouse rose on the outside, but her heart was as quietly passionate as a tropical blossom.

You could argue that Hepburn sometimes looked like a type (think of her in the 1952 "Pat and Mike," strong and lean and dressed in fabulous golf outfits and tennis whites, the picture of everything we imagine money and breeding to automatically confer), but she never acted like one. Mid-career, she reveled in one of her greatest gifts: Her peppery comic timing flourished in her many collaborations with her on- and off-screen partner Spencer Tracy, among them the 1949 "Adam's Rib," "Pat and Mike" and the 1957 "Desk Set." On-screen Tracy never humored or babied her; he was someone she could stand up to. At their first meeting she asked, coquettishly and a bit arrogantly, "Am I too tall for you, Mr. Tracy?" "Don't worry, Miss Hepburn," he answered, "I'll cut you down to size."

Their chemistry brought out the best in both of them as actors. It's also worth noting that when Hepburn made "Adam's Rib," she was 42, the age at which most contemporary actresses begin to fear (with good reason) that Hollywood is going to squeeze them out. Perhaps because Hepburn's image traded as much on smarts as it did on glamour, her career continued to thrive and deepen. But whatever the reasons were, she built a career that lasted well into her 70s. She did have a tendency to act "dear" in many of her later roles (her last movie appearance was in the 1994 Warren Beatty-Annette Bening vehicle "Love Affair"), playing the beloved figure she had become instead of the spiky ones that ruffled audiences. But those missteps didn't happen until relatively late in her career. With pictures like "The African Queen" (1951), "Long Day's Journey Into Night" (1961), "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" (1967) and beyond, she found roles that would allow her to age gracefully but without that dignified sheen of dullness that so many actresses cultivate, knowingly or otherwise.

But it's always the Hepburn of the '30s, full of promise and beans, that I find most moving -- not because she didn't mature and improve as an actress (in many ways she did) but because in those early movies, I see a woman who must have known she was like no woman who had ever come before. Did it hurt or confuse her, just a little bit, I sometimes wonder? We can't really know. But instead of trying to smooth herself out, she reveled in the rougher textures of what she had to offer, even though doing so didn't immediately reward her. She didn't care that people didn't like her right away -- she must have figured that in time she'd win over the right ones, the smart ones, and to hell with everybody else.

Before long, plenty of people did like her, often for all the right reasons. She built a career she could be proud of -- the image that came with it was just a bonus. She was dignity itself, but with a heart, a soul and a sense of humor. She was never box-office poison. She was its lifeblood.

Shares