If you need any further evidence that independent film is failing its mission of giving a chance to movies that might otherwise get overlooked, consider the fate of "Lift." This sharp, brainy, unclassifiable first film by the directing team of Demane Davis and Khari Streeter was praised when it premiered at the 2001 Sundance Film Festival, and was later featured in the New Directors, New Films program at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. But even with that buzz, "Lift" couldn't get a distributor. It ran on Showtime -- which deserves credit for providing a home to a slew of indie movies left high and dry -- and came out just last month on DVD, which is how I saw it.

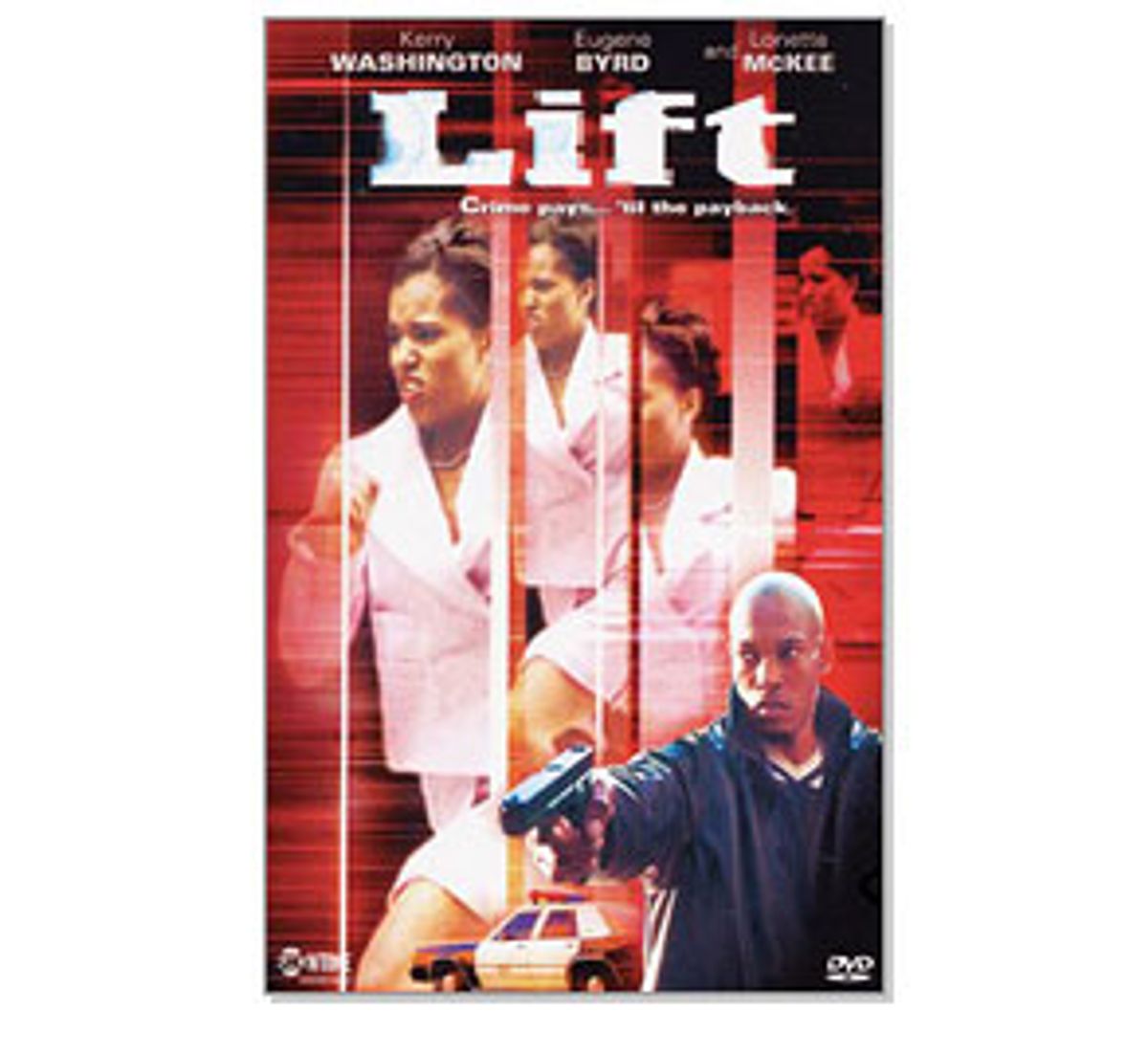

With the major studios having taken over most independent distributors, it's not too hard to see why "Lift" got left out. The movie, by an African-American directing team and with a black cast, can't be shoehorned into the clichéd terms routinely used to sell movies to black audiences. Even so, the DVD cover makes it look like an urban action movie. When I went to look for it at the Virgin Megastore in Times Square, I found it in the "Black Cinema" section, the segregated catch-all for everything from "Malcolm X" to "Hell Up in Harlem." As I see it, the largely white, liberal, educated audiences that turn out for indie movies tend to like their minorities downtrodden or representative of an easily diagnosed social problem.

What this means in practical terms is that two obviously talented young American filmmakers are penalized because they make a movie that doesn't think in stereotypes, doesn't provide easy answers and doesn't flatter a potential audience's portrait of itself as good, caring, concerned people. In other words, Demane and Streeter have the bad luck to be blessed with brains and taste. And they are at the mercy of exactly the same system that indie film was supposed to circumvent.

Film festivals are full of movies that face the same fate as "Lift." Two of the best American independent films of recent years, Michael Gilio's "Kwik Stop" and Ching C. Ip's "See You Off to the Edge of Town," just to name two, will not be coming soon to a theater near you, although they are exactly the sort of small, observed picture that indie film was supposed to champion. And things are not going to get better. To the studio dummies who've gotten into indie distribution, an indie success is "My Big Fat Greek Wedding" (which may prove to be the same kind of disaster for indie film that "Star Wars" was for mainstream ones). The next big, dumb, clichéd ethnic family comedy will set the suits salivating, while a movie like "Lift," which isn't like anything else, draws a blank.

Next to the way talented young American directors are being robbed of their chance at recognition, the thievery on display in "Lift" seems like small potatoes. The protagonist of "Lift" is Niecy (Kerry Washington), a young clerk at an upscale Boston department store. Her eye for fashion is so keen that her older boss steals credit for Niecy's display work, and she's so impeccably dressed and made up that she probably looks better than most of the customers she waits on.

She's also a first-class thief, equally adept at shoplifting or using stolen credit cards or forged checks to stock up her supply of designer pieces. They're not all for her. In an early scene, Niecy, fresh from dropping thousands with a stolen card, parades her wares into a beauty salon and sells them at a discount to beauticians and customers alike. It's strictly cash, and since she has no intention of paying off those stolen credit cards, it's all profit.

The rationale that "Lift," which was written by Davis from a story by him and Streeter, offers for Niecy's thievery is that she's seeking the approval her mother withheld from her. There have never been mother-daughter scenes like the ones between Washington and Lonette McKee. McKee's Elaine is just as concerned with appearances as Niecy. She belongs to a generation of black women old enough to still admire her daughter's "good hair." But when the two of them meet for lunch, she's more interested in the spot on Niecy's Armani suit than in news of her daughter's life. When Niecy tells her Elaine can't find the DKNY coat she's promised her, you see Elaine's attention immediately drift away.

You can't give a performance like McKee gives here if you're worried about being liked. Elaine can't hide any of her resentments, at the father who beat her, at the husband who walked out on her, at her job as a legal secretary in a tony law firm. Everything about the way Elaine carries herself tells you she believes she was meant for something more. Life has continually shortchanged her, and she's not about to forgive it. Right up until the script calls for Elaine to (unconvincingly) soften, McKee gives a performance so flinty you feel like you could cut your fingers just by touching her. And the character's resentment links up in your head with McKee herself. It's easy to believe a woman like Elaine can feel cheated when she's played by a stunning, talented actress who's never had the career she should have.

The duets between Washington and McKee, with Niecy making overtures and Elaine rebuffing her, feel uncomfortably true. But using Niecy's desire to win her mother's love as a motivation for her theft is pat psychology. "Lift" offers a more unsettling motivation. The title is a double meaning, referring not just to shoplifting but to Niecy's desire to lift herself up. The designer outfits she wears when she's working a store, the DKNY trench coats and pashminas, are the disguises by which she's accepted in this chic, perfect world.

Niecy knows that a young African-American woman dressed less than perfectly would immediately come under suspicion. On some level, she even shares those prejudices. She revels in her ability to fool the clerks. (In one scene, out of pure spite, she drops a security tag in the open bag of a white woman so the woman is stopped on her way out of the store.) Her boyfriend Angelo (Eugene Byrd) has given in to Niecy's entreaties to quit working for a crew of thieves. But she refuses to believe that what she's doing is no different, even when she goes to Angelo's old boss, Christian (Todd Williams), for help in setting up her own scheme.

Washington gives a much warmer performance than McKee, but Niecy is still her mother's daughter. She's high-handed and insulting with a black co-worker who doesn't have the same sense of style she does. At a party at Christian's house, she holds herself aloof from the bling-bling surrounding her. She's in Nicole Miller instead of Enyce or Baby Phat, and in Niecy's mind that puts her on a higher plane.

The style that Niecy gravitates toward is not routinely marketed to black women. Beverly Johnson, Iman, Naomi Campbell and Alek Wek are still the exceptions in the magazines Niecy devours. Part of the racial implications here have to do with the story being set in Boston, the most segregated city in the Northeast, which makes its loudly proclaimed liberalism hypocritical at the very least. (There is a bus in Boston that runs along Massachusetts Avenue all the way from Roxbury, a historically black neighborhood, into Harvard Square. In the '80s you could see black people loaded down with groceries boarding the bus to go home from Cambridge because there were no supermarkets in their own community -- there are still no movie theaters there.)

Maybe you have to have lived in Boston to understand what it means to Niecy to pull the wool over the eyes of stores where the presence of black people is usually a red flag for the security staff. Davis and Streeter perhaps push the irony by scoring all of Niecy's shoplifting scenes to classical music. That's also a canny choice not to fall into the hackneyed devices of "urban" filmmaking. Had Demane and Streeter used the hard, staccato beats of hip-hop they would merely have been calling attention to Niecy's race instead of commenting on the narcotic placidity of the world she's buying into -- all those pristine shops whose goods promise a better life, where worry has been banished and where no one has to hesitate before plunking down $300 for a blouse.

But "Lift" is no more a simplistic brief against consumer culture than it is solely about racial exclusion. Demane and Streeter understand what it is to want. They understand the desire to give in to the luxury of fine silks and cashmeres and Niecy's desire to belong to a world that won't automatically size her up and find her lacking because she's a young black woman. Niecy might be a descendant of Susan Kohner's character in Douglas Sirk's "Imitation of Life," a young light-skinned woman who passes as white because, ironically, it's the only way people see her instead of her race. "Lift" cuts deeply and almost cruelly when those desires are reflected back at Niecy in their ugliest forms. Pregnant by Angelo, Niecy tells her girlfriend she's not sure what she's going to do and is told, "Girl, you know you got to keep that baby. Everybody has one."

"Lift" wouldn't work if Kerry Washington weren't able to make us understand Niecy's longing. Her presence here is something like a slap in the face if you know her, as most of us do, only from the roles she played in "Our Song" and "Save the Last Dance." Washington is one of the freshest presences in the movies. Her full cheeks give her an almost childlike adorability, and when a harsh remark comes out of Niecy's mouth, or when she nonchalantly cuts the security tag on a cashmere sweater, she's asking us to hold two contradictory ideas about her in our heads at the same time. She's asking us to see Niecy as another of the nice girls she has played, but one who is capable of duplicity and even snobbery -- but also to understand rather than judge her. Washington is alive every moment she's on screen. You feel like you can see her thinking and you can read every emotion, even the briefest, that crosses her face. To feed further fuel to the issues "Lift" addresses, this performance by an exceptional young actress has gone largely unseen.

Demane and Streeter make a few beginner's mistakes. A fantasy sequence where a funeral turns into a fashion show contrasts garishly with the low-key assurance of the rest of the movie. And they don't know how to end their movie, opting for a pat, reassuring reconciliation rather than the tougher finish the movie calls for. But these are minor flaws on a movie that's so fluidly made, culturally astute and confident in its ability to address issues indirectly (that is, to dramatize instead of preach). They may be those rare filmmakers who are able to make a movie that feels open without seeming unformed.

We're lucky to be in an era when a neglected picture like "Lift" can find an audience on home video. Not too long ago, most of us had no hope of seeing a movie that wasn't picked up for distribution. But we shouldn't feel too lucky. It's great that "Lift" is accessible to viewers, but it's crummy that a movie that doesn't hide its intelligence or diminish the complexity of its story -- and one that doesn't turn its black characters into cultural caricatures -- can't find a distributor. The fate of "Lift" should stick in our minds next time we hear someone talking about the wonderful things the "indie revolution" has done for American movies. If a terrific movie that doesn't easily fit into preconceived categories can't get picked up, why the hell does indie cinema exist?

Shares