Stephanie Zacharek's 10 Best Films

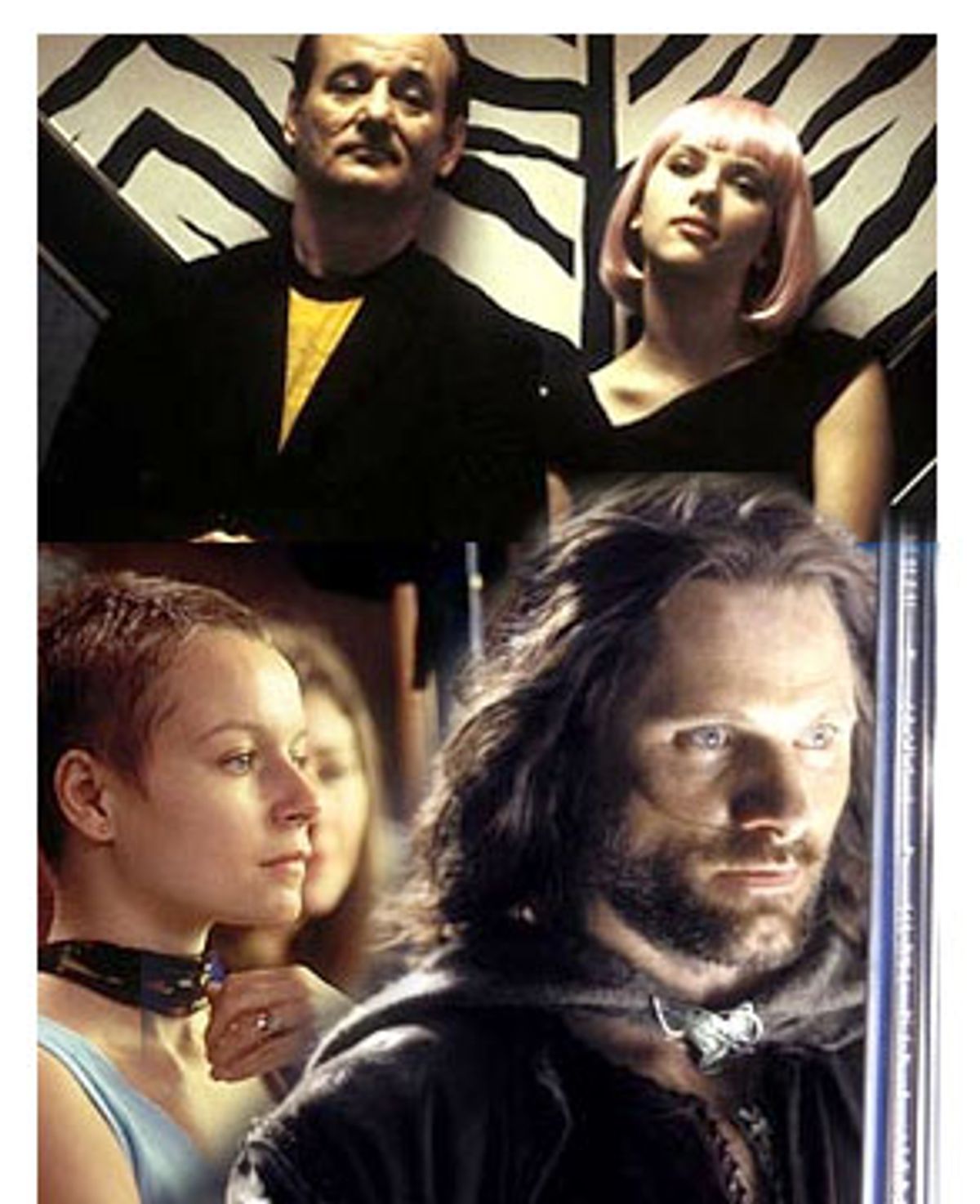

"Lost in Translation" (directed by Sofia Coppola). A jet-lag romance not just for the modern age, but for the ages. Coppola meditates on the nature of intimacy and dislocation, sustaining a mood of rapturous melancholy that few older, more experienced filmmakers have matched. The characters played by Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson circle each other on currents of sleeplessness: Both suffering from travelers' insomnia, they repeatedly drift toward their accidental meeting spot, the bar in the Tokyo hotel where they're staying, as if they were tuned in to the same silent whistle. Johansson is luminous and touching; Murray, whose expressiveness radiates from within instead of just beaming off the surface, turns in the performance of a lifetime.

"In America" (directed by Jim Sheridan). A man moves his young family from Ireland to Hell's Kitchen, NYC, and figures out the difference between surviving and living. There's something emotionally rough-hewed about Sheridan's movie (which is based loosely on his own experience and that of his two daughters, who co-wrote the movie with him). Its edges aren't polished and smoothed under, which may be why the picture cuts so deep.

"A Mighty Wind" (directed by Christopher Guest). Satire made by a staunch humanist. Guest's mockumentary about '60s folk singers is improvisational comedy that feels immediate and spontaneous and jazzy, yet it has so much emotional heft -- particularly in the performances of Catherine O'Hara and Eugene Levy -- that it leaves an echo of melancholy in its wake.

"Spellbound" (directed by Jeffrey Blitz). This documentary about the National Spelling Bee is more suspenseful than most modern thrillers, and better made, too. But what really sets it apart is the way it makes a kind of straightforward poetry out of the loneliness, the diligence and, yes, the excitement of being a smart kid.

"American Splendor" (directed by Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini). Paul Giamatti is crotchety and wonderful as comic-book writer Harvey Pekar, an unrepentant crank who wouldn't know a good mood if it peed on his leg. But Pekar's dirty little not-quite-a-secret is that he's actually a closet idealist, and both Giamatti and the filmmakers understand that. Pekar is so open to the world around him, it's no wonder he's in a bad mood most of the time. Then again, the only way to take the measure of humanity in all its perplexed glory is to keep our receptors on at all times. How do you put that in a movie? I don't quite know, but Berman, Pulcini and their actors sure pulled it off.

"Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King" (directed by Peter Jackson). I wonder if the massive popularity of the honor-sogged "The Last Samurai" in the first few weeks of its release wasn't at least partly because moviegoers were treating it as a stopover on the way to "The Return of the King." Of the two, "Return" is the movie that really scrutinizes the meaning of honor in battle, cutting straight to the spiritual underpinnings of warriorhood. (I'll take Aragorn's nightmares over Algren's, any day.) Or, at the very least, "Return" is a magnificent and purely satisfying -- and, yes, devastating -- cap-off to one of the greatest epic movie adventures of all time. Accept no substitutes, no matter how pseudo-spiritual or neo-historical they pretend to be.

"Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World" (directed by Peter Weir). Yet another movie about bravery, honor and duty. But as with "Return of the King," you don't walk away from it praising the worthiness of its themes -- instead, you're left with a true and deep sense of the rueful compromises that rousing victories often demand. Russell Crowe gives a performance that's heroic not just in the most obvious sense of the word, but also in the most subtle: His Jack Aubrey understands that every decision has a potentially devastating downside, and he carries that knowledge both in his heart and on his nobly squared shoulders. "Master and Commander" is a magnificent historical adventure with a throbbing heart. And there's mournful grandeur in cinematographer Russell Boyd's every shot.

"To Be and to Have" (directed by Nicolas Philibert). A delicately calibrated documentary about a one-room schoolhouse in the French countryside and the teacher who guides the students in attendance there, from tots to young teenagers. "To Be and To Have" illuminates both the vocation of teaching and the work of being a student, without sentimentalizing, or underestimating, either. It's a small-scale picture that does the same thing a great teacher does: It keeps you thinking long after you've left your seat.

"School of Rock" (directed by Richard Linklater). Forget makeover shows: The real transformative power lies in rock 'n' roll. Jack Black plays an unshaven lout who takes a bunch of square schoolkids and shows them how to channel their inner cool. This picture moves, driven by intelligence and craftsmanship and goofiness. Hollywood comedies have a bad reputation these days, for some very good reasons. But Linklater leads the way in showing that you can surf the mainstream without being dragged under by it.

"Masked and Anonymous" (directed by Larry Charles). The most picked-on movie of the year was also one of the weirdest and most provocative. In this parallel-universe parable, a troubadour masquerading as Bob Dylan (or is it the other way around?) reflects on American idealism, fame and the commodification of music. No, it's not linear -- but then, neither is Dylan.

Honorable Mentions: Robert Altman's "The Company," Lisa Cholodenko's "Laurel Canyon," Terry Zwigoff's "Bad Santa," Jacques Perrin's "Winged Migration," Claire Denis' "Friday Night," Tom McCarthy's "The Station Agent," Patty Jenkins' "Monster," Seijun Suzuki's "Pistol Opera" and John Malkovich's "The Dancer Upstairs." And last but not least, Mark Waters' highly entertaining "Freaky Friday," particularly because Jamie Lee Curtis is so damn good.

Charles Taylor's 10 Best Films

"Lost in Translation" (directed by Sofia Coppola). Coppola is so adept at catching the reverberations of evanescent moods that she can make the most intimate moment in this romance across time zones the one where Bill Murray clasps the foot of the sleeping Scarlett Johansson. "Lost in Translation" uses contemporary borderlessness as a metaphor for the emotional state of the movie's two chaste lovers, Murray and Johansson, as they wander the corridors of a Tokyo hotel. In outline, it sounds like one of the anomie fests that made people swoon over Antonioni and Resnais. It's more like a dreamy version of a classic romantic comedy about the modern predicament of feeling like you're everywhere and nowhere. The faces of Johansson and Murray (in the performance of his life) are so eloquent that they demonstrate how, for actors, words are a last resort.

"In America" (directed by Jim Sheridan). Set in a Hell's Kitchen tenement, Sheridan's autobiographical story of an Irish family reeling from the loss of a child is both tender and robust. In the face of the fierce emotion that powers the movie, sentimentality doesn't stand a chance. Instead of exhausting your capacity to feel, Sheridan keeps deepening it. The performances by the astonishing Samantha Morton, Paddy Considine, the wonderful newcomers Sarah and Emma Bolger, and Djimon Hounsou all radiate with an emotional commitment that matches Sheridan's. "In America" sweeps you into its rough, loving embrace and then puts you back in the world, safe and sound, telling you the life waiting outside the theater is a gift.

"Spellbound" (directed by Jeffrey Blitz). This splendid documentary about the National Spelling Bee is not only moving and funny but also about as suspenseful as a movie can get. Blitz gives us acute mini-portraits of eight contestants, some of whom -- like Ashely, the African-American girl from Washington, D.C., who gets done up in her finest to compete -- you can't help but fall in love with. Perhaps the moment that sums up the movie's essential decency is when a born-again preacher prays for the success of one kid, a member of his congregation, but asks the Lord to remind him that being a good person is more important. That's how Blitz is able to make the Bee almost unbearably exciting while making the losers seem anything but.

"The Good Thief" Neil Jordan's best movie, this sensuous, elegant remake of Jean-Pierre Melville's "Bob le Flambeur" is looser, freer, hipper than the original. Jordan replaces Melville's hardboiled romantic fatalism with the story of a battered gambler who regains his harmony with a lifetime of taking risks. The movie is warm and mellow but with a kick. There's a playful springiness that keeps any hint of hardboiled sogginess at bay. As Bob, Nick Nolte is a magnificent wreck, an image of battered masculinity that is far more beautiful than any preserved and mellowed good looks could ever be. As the young prostitute who becomes Bob's good-luck charm, the charming Russian actress Nutsa Kukhianidze makes her way through the movie like a languid breeze.

"Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King" (directed by Peter Jackson). The conclusion to the Tolkien cycle reveals that the film is not a trilogy but one gigantic movie. This, the last third, plays upon all the emotions we've developed for the characters, echoing moments from the first two installments and enriching their emotional depth. The entire cast rises to the occasion, particularly Sean Astin, Andy Serkis, Viggo Mortensen, and the weirdly talented Miranda Otto. You watch this picture marveling not just at what's on-screen but also at Jackson's ability to sustain it so beautifully. It's one of the great achievements in fantasy filmmaking. Savor it -- because as soon as it's over you're hit by the melancholy realization that there won't be another one to look forward to next year.

"To Be and to Have" (directed by Nicolas Philibert). This documentary about a year in the life of a one-room French schoolhouse is a portrait of the teacher as artist, and about teaching as a form of love. Extraordinarily evocative, the movie brings back emotions you may have forgotten you ever had, the wonder of learning letters and numbers and, later, being able to form sentences. In its finest moments, when George Lopez comforts a student whose father is sick or encourages a painfully shy girl, the movie is a masterpiece of empathy.

"The Company" Robert Altman's film about the work and lives of a ballet company (Chicago's Joffrey Ballet) features some of the most beautiful dance numbers ever put on film (including a Lar Lubovitch pas de deux danced by Neve Campbell and Domingo Rubio to "My Funny Valentine"). The flip side of Altman's tortured "Vincent and Theo," which was about the agony of making art, "The Company" is about the joy of discovering the amazements you're capable of. Altman, still making great movies in his '70s, finds affinity with these young dancers who have only a short time to practice their art. He's managed to defy time. "The Company" is lighter than air and yet it seems to contain everything Altman has learned about making movies.

"School of Rock" (directed by Richard Linklater). A classic American movie comedy. Jack Black throws everything he has at the role of a substitute teacher turning his class into a rock band and, somehow, manages not to exhaust either himself or the audience. Richard Linklater pulls off the feat of making a completely accessible mainstream comedy while staying true to himself. "School of Rock" is pure pleasure, and the joy on of the faces of the kids as they strut their stuff is the year's sweetest payoff.

"Masked and Anonymous" (directed by Larry Charles). Directors of jazz movies have long gotten away with shoddy structure by claiming they were aping the improvisatory nature of jazz. Larry Charles' rambling film starring Bob Dylan as a once-famous singer released from prison to play a benefit for America's elected dictator works exactly like a Dylan song, which is to say it's oblique, bleak, funny, prophetic and stirring -- and critics reacted as though they'd never heard a Dylan record in their lives. The movie received this year's most uniformly dunderheaded reviews, which were shocking not only for their inability to see what Charles and Dylan were up to, but for their overt hostility to a filmmaker who tried something unusual -- which only made the movie's vision of art reduced to fodder for the dominant polity all the more pointed. Dylan fulfills exactly the same function he does in his songs: not a participant but an observer, meeting all sorts of characters, listening to their tall tales, rants, threats, jokes and warnings. Among the images of a third-world America coming apart, a moment of unexpected peace: Dylan and his band singing "Dixie," which becomes a love song to a lost republic that may exist only in the country's unrealized aspirations.

"demonlover" (directed by Olivier Assayas). This meditation on the seductions of technology is a mixture of folly and brilliance that goes willfully off the rails. Even at its most lucid, the movie's ideas can seem both shallow and paranoid. And the film is still one of the most vital pieces of moviemaking in recent memory, telling us more about the tenor of this moment than perhaps we're ready to acknowledge. Assayas takes the measure of a borderless, transient world in which the Internet, globalization, and corporate mergers and takeovers have obliterated any sense of continuity or personal loyalty. The movie is exhilarating and made to rob your sleep. As the corporate spy who is both ahead of and behind the game at every turn, Connie Nielsen gives a performance that is both icy and shockingly raw, composed and on the constant verge of lyrical hysteria.

Honorable Mention (in alphabetical order): Directors Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini's "American Splendor"; Terry Zwigoff's "Bad Santa"; John Malkovich's "The Dancer Upstairs"; F. Gary Gray's "Italian Job"; Aki Kaurismäki's "Man Without a Past"; Peter Weir's "Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World"; Christopher Guest's "Mighty Wind"; Patty Jenkins' "Monster"; Carma Hinton, Geremie R. Barmé and Richard Gordon's "Morning Sun"; Carl Franklin's "Out of Time"; Seijun Suzuki's "Pistol Opera"; Tom McCarthy's "Station Agent"; Jacques Perrin's "Winged Migration."

The Miramax Award for the Annual Holiday Prestige Turd: "Cold Mountain"

The Emperor's New Clothes Award: "Elephant"

Andrew O'Hehir's 10 Best Films

"House of Fools" (directed by Andrei Konchalovsky). You'll never see another film about the Chechen conflict that has '80s pop star Bryan Adams in it. Hell, you'll never see this one. But you should. A heartbreaking and sensual near-masterpiece from Konchalovsky, an all-but-forgotten avatar of Soviet cinema's lost golden age. (He directed "Asya's Happiness," "Siberiade" and the strangely great Hollywood film "Runaway Train" -- as well as "Tango and Cash," with Kurt Russell and Sylvester Stallone!) This tragic and unforgettable movie would have been his triumphant comeback if, well, if it hadn't disappeared without a trace. There may or may not be a God, but he's not watching out for Konchalovsky.

"Ten" (directed by Abbas Kiarostami). Yeah, Kiarostami is the Iranian director best known in the West (which means, apparently, that some Iranians think he has sold out -- call it the Kurosawa complex). But that doesn't mean any Americans actually see his films. Shot on digital video via a fixed "dashboard cam," while a middle-class Tehran woman drives her impossible son around, bickers with her sister, picks up a religious pilgrim and then a prostitute, "Ten" is experimental even by Kiarostami's standards. It played hardly anywhere. It's a revelation.

"The Dancer Upstairs" (directed by John Malkovich). The indie-film hero's directing debut is a near-perfect marriage of political thriller and existential art film. A decent South American cop (the great Javier Bardem) serving a corrupt regime must try to find the elusive terrorist leader who has an entire nation spooked. It's partly about Peru in the era of the transcendentally evil Shining Path movement, and partly a story about the untrustworthy nature of love. The gorgeous Laura Morante is the dance teacher he falls for; the unforgettable tune on the soundtrack is Nina Simone singing Sandy Denny's "Who Knows Where the Time Goes?"

"Carnage" (directed by Delphine Gleize). European art cinema continues not to die, despite all reports to the contrary. This debut feature from Gleize, a 30-year-old French director, is the story of a group of strangers all over Europe linked, in an almost religious sense, by the corpse of an Andalusian bull. It's probably the most beautiful film I saw all year. Gleize is more than anything else the spiritual heir to Luis Buñuel ("Carnage" even stars Buñuel actress Angela Molina, along with Chiara Mastroianni, daughter of Catherine Deneuve and Marcello Mastroianni), but that's just fine with me. Despite the title and the concept, this isn't a brutal or "difficult" film; it casts a cool eye on life and death but treats its large cast with a whimsy very close to tenderness. Another marvelous flick no one saw.

"The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King" (directed by Peter Jackson). Much as I will always love "The Fellowship of the Ring" (which, truth be told, is by far the best of Tolkien's original volumes), Jackson really did save the best for last. It's far too early to predict how these movies will age, but Jackson has clearly kicked George Lucas to the curb and created the biggest and best pop epic since Francis Ford Coppola's "Godfather" series.

"The Matrix Reloaded" (directed by Andy Wachowski and Larry Wachowski). Oh, shut up about the dancing and the dreadlocks (as well as about how great your life was in 1999). Somewhere inside, you know it was terrific -- that it opened up new possibilities the original film had never imagined. The fact that the Wachowskis had no way to follow up, and that "Revolutions" was basically a dog, doesn't change that.

"Lost in Translation" (directed by Sofia Coppola). You've read enough about this movie by now, haven't you? Emotionally and visually, it's pitch-perfect; with this one film, Sofia Coppola jumps to the head of the indie-god class. (Quentin's got to get out of the basement and return all those Hong Kong videos.) Bill Murray deserves the Oscar and might even get it; Scarlett Johansson is almost as good but won't win anything (except the, um, hearts of guys all over the world). Making a movie about Yanks in a bizarro-world foreign culture is kind of cheating, and using karaoke scenes as a shorthand for falling in love is really cheating. But somehow Coppola makes it all work; she takes the fraught topic of older-guy/younger-woman love and cooks it down to irreducible human reality. It's a miniature, but it's a wonderful miniature.

"Old School" (directed by Todd Phillips). All right, I sort of put this on the list to horrify you. But, hey, if Hollywood does one thing well it's moronic dude comedy, and frankly it's an underappreciated genre. (I'm still steamed about the bad reviews that "Saving Silverman" and "Dude, Where's My Car?" got.) Here are the facts: a) It's hysterically funny; b) it's still Will Ferrell's most blissful performance, "Elf" or not; c) it does not either glorify older men gamin' on young girls -- in fact, it does quite the opposite; and d) it's just flat-out funnier than "School of Rock," which was pretty good but in a cleaned-up, so-you-can-take-the-wife-and-kids kind of way.

"Under the Skin of the City" (directed by Rakhshan Bani Etemad). This working-class family melodrama from a female Iranian director best known for her documentaries is well-made, affecting and humorous, and it will open your mind to the realities of that much-misunderstood country. Bani Etemad fearlessly takes on the subjugation of women, political corruption, and the widely despised rule of the ayatollahs, as well as the pell-mell infusion of Western capital, all while portraying the family's struggle to hold on to its house and save an abused daughter from a life of prostitution.

"Marooned in Iraq" (directed by Bahman Ghobadi). The story of George W. Bush. I kid, I kid! This isn't as starkly memorable as Kurdish-Iranian filmmaker Ghobadi's previous film, "A Time for Drunken Horses," but it's a more accomplished and far more eccentric work. Among other things, it's a comedy about a group of hapless Kurdish musicians, well-known in their limited universe, who undertake a foolhardy mission to find a missing woman across the border in Iraq. They are robbed of almost everything, abducted by a local warlord, and forced to play a wedding; they encounter an empty village, presumably gassed by Saddam Hussein. And it's all pretty funny, in a grating, Three Stooges kind of way. Also, by the end, it's a heart-wrenching tale of nobility and survival, set against some of the most dramatic scenery you've ever seen.

Shares