The camera crews from "Entertainment Tonight" and "Access Hollywood" were clearly vexed: Unlike at other banquets held during the busy season leading up to the Oscars, full of famous faces, no one streaming into the International Ballroom at the Beverly Hilton on Feb. 18 was even remotely recognizable to them. Most of the attendees' garb looked as though it was bought off the rack at Nordstrom, and no one was wearing gaudy baubles borrowed from Harry Winston. When interviewed by the TV and radio reporters positioned behind the black velvet ropes, the evening's award winners were more likely to discourse on compression algorithms, cloth-simulation software or robotic camera mounts than to grin and gripe about the nonexistent limo gridlock outside the hotel.

The occasion was the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences' annual Scientific and Technical Awards, which each year's Oscar host fleetingly refers to as "a ceremony held earlier" before cueing a 30-second video summary of the event. There's usually a grand total of one celebrity at the Sci-Tech Awards: the evening's host. The banquet's organizers at the academy have a solid record of landing actresses on the way up, including Charlize Theron, Kate Hudson and, last year, Scarlett Johansson. This year's host was Rachel McAdams, seen recently in "The Family Stone," "Wedding Crashers" and "The Notebook."

As someone who identifies less with the international megacelebs who'll strut into the Kodak Theatre on the first Sunday in March, and more with the working stiffs behind the scenes trying to keep the directors, cinematographers and editors happy, I'd always been curious about the Sci-Tech Awards. Did they have anything in common with Hollywood's biggest night, aside from plastic statues of Oscar guarding every pillar?

The Sci-Tech Awards celebrate the mechanics of moviemaking, recognizing "any device, method, formula, discovery or invention of special and outstanding value," according to the academy. Awards this year went to a system that can keep a movie camera level even if it's on a boat in the middle of a roiling ocean; the graphics research that makes the characters in Pixar movies more realistic looking; and a newly designed air bag that's less likely to cause stunt people to bounce off and be injured when they hit it from great heights. There are no "For Your Consideration" campaigns in advance of the Sci-Tech Awards, no seat fillers in the audience and, amazingly, no time limits on speeches. "It has never been a problem," says Rich Miller, the administrative director at the academy who has overseen the Sci-Tech Awards since 1988. "We haven't had to install the microphone that starts descending into the floor when you've talked too long."

The ballroom last Saturday wasn't pervaded by tension or anxiety -- all of the winners had been announced a month before. So everyone could enjoy the four-course dinner without worrying about going home empty-handed, and no one had to fake an "I'm so happy for that jerk who edged me out" smile. At my table were three winners, J. Walt Adamczyk, Michael Sorensen and Alvah Miller; the trio of engineers and computer scientists won for a remotely controllable camera system that can execute the exact same moves, take after take, and for "pre-visualization" software that gives directors an early, rudimentary view of how computer-generated sets and special effects will look once they've been integrated with the live-action footage. The rig has been used in "Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events" and "Spider-Man 2."

Miller said he'd won "five or six" Sci-Tech Awards in his career, and he'd also been a guest at the main-event Oscars. "This is better than the Oscars," he said. "The Oscars are too long and too boring."

McAdams took the stage after a highlight reel of her film performances had been shown. She explained apologetically that the audience was probably "more familiar with my work as a scientist. I recently abandoned my research on cold fusion, because it was just too cold." Toothpick thin, she wore a glittery gold sleeveless gown. McAdams didn't deviate at all from the jargon-laden script that scrolled across the teleprompter, but she did keep things moving at a good clip. (As with the other Oscars, the evening featured one painful-to-watch special performance, in the vein of Rob Lowe and Snow White singing "Proud Mary" in 1989: ventriloquist Jim Barber, direct from Branson, Mo., who trotted out dummy after dummy, and eventually had two Academy members from the audience up onstage lip-syncing to "Stop! In the Name of Love" in sequined shifts.)

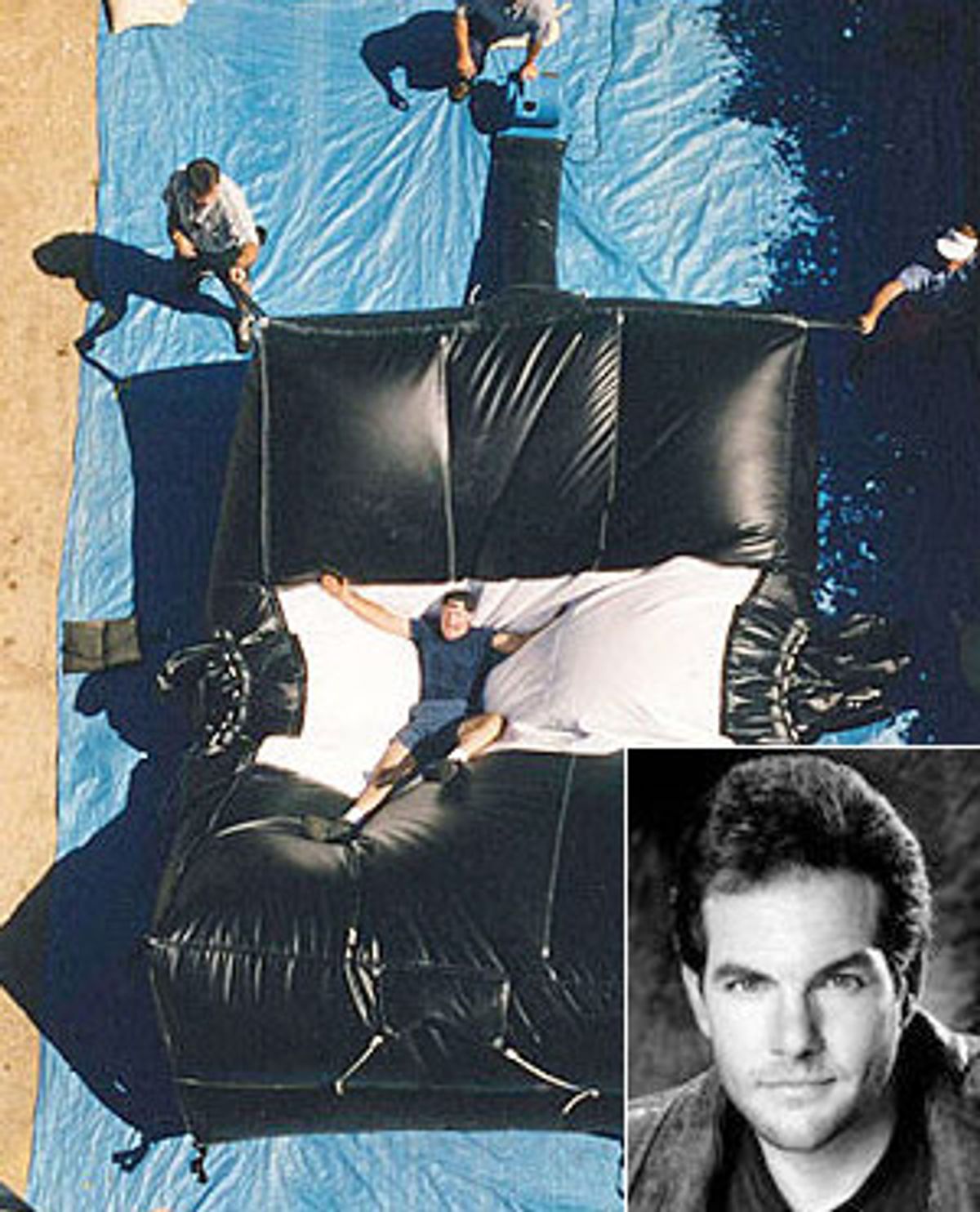

The evening's first award went to Scott Leva, a stuntman and stunt coordinator ("Superman," "Toxic Avenger," "Collateral") who developed the Precision Stunt Airbag. Inflated on the ground to catch a stunt person performing a high fall, Leva's air bag is designed to pull the performer in, whether he or she lands in the center or close to an edge. Leva said he was sorry that stuntman Paul Dallas, a friend, wasn't alive to see him receive the award. (Dallas died in 1996, doing a fall for an episode of the TV series "L.A. Heat.")

Winning an award alongside Pixar president Ed Catmull, Pixar programmer Tony DeRose said he was "on a mission to show kids how cool math and science can be, and this award will help get that message across." Microsoft researcher John Platt, receiving an award for his insights into "elastically deformable models" (at the other Oscars, the term would refer to arm candy that'd had too much work done), thanked McAdams for lowering his "Kevin Bacon number" to three, and his neighbors for watching his kids. Laurie Frost, a Brit who invented a remote-controlled camera system in 1976 that allows camera operators to stay a safe distance from dangerous shots, recalled having to take out a second mortgage on his house to cover the costs of its development. (Rich Miller explained that the academy tends not to bestow awards until a new technology has been widely adopted in the industry -- and, sometimes, even later.)

At the Sci-Tech Awards, there are three tiers of honors, and the process for choosing the winners involves more research -- and less DVD viewing -- than the other Oscars. If a nominated technology is portable enough, its inventor brings it to the academy for a demonstration; if not, a small team goes on a field trip. With Leva's air bag, they watched as stunt performers -- including a 9-year old -- plummeted into it from 30 feet up. Toward the end of the year, the academy's Scientific and Technical Awards Committee votes by secret ballot on which technologies are most worthy. A technology can win a certificate (the lowest rung of Sci-Tech Award), a plaque or an Oscar.

"We give very few Oscars," said Miller. "They're mostly for inventions that change the way movies are made. Steadicam is a good example. There are almost no movies made today that don't have a Steadicam shot in them." (Two of the most famous shots using a Steadicam, which permits a camera to remain motionless while the camera operator is walking or running, are the scene in "Rocky" where Sylvester Stallone ascends the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the five-minute shot that opens "Goodfellas.") Miller said that only 44 Oscars have been awarded for scientific and technical achievement. None was awarded this year: Recipients instead received plaques, certificates, one honorary medallion and an honorary Oscar statuette, which technically wasn't an Oscar Oscar.

"My impression is that the Sci-Tech Awards are generally not that political," said Bill Warner, the founder of Avid Technology. Warner won twice for developing a digital system for editing movies -- including receiving the coveted Oscar statuette in 1999. (Most Hollywood movies are now edited on an Avid system.) "I feel like it's a meritocracy," he said. "Some of these companies that win are really small, and some of the people are so freaking brilliant. You wonder, how did they figure out how to make that flying camera?"

The Sci-Tech Awards are like Oscar's older, brainier brother, who isn't very good at small talk, and spends his disposable income on outfitting his basement workshop with new oscilloscopes rather than on teeth whitening and tanning. And since they were first given out in 1930, the Sci-Tech Awards have always existed in the shadow of their flashier sibling. The Academy Awards get billboards all over Los Angeles; the Sci-Tech Awards didn't even get a sign in the lobby of the Hilton. In the past, the Sci-Tech Awards have been doled out without a gathering to mark the occasion, or palmed off in a hurry during the commercial breaks of the televised Academy Awards. "During the commercial breaks, people don't always sit still and pay attention," observed Rich Miller.

But the Sci-Tech Awards this year are coming up from the basement for a bit of air: The Discovery Channel is preparing a one-hour documentary, hosted by Dave Foley, about the ceremony, the honorees and their inventions. "Science on the Red Carpet" amounts to perhaps one one-thousandth of the airtime that will be devoted to the Oscars, Oscar parties, Oscar fashion and the performance of first-time Oscar host Jon Stewart. But it's a lot more attention than the Sci-Tech Awards have ever gotten before. (The Discovery Channel producers had to install their own patch of crimson carpet at the front door of the Hilton, though -- the Sci-Tech Awards don't usually feature a long red rug.)

Garrett Brown, the inventor of Steadicam, says he isn't happy that the Sci-Tech Awards are often referred to as the "nerd Oscars" or "geek Oscars" by those who attend the main ceremony. "Don't call it the nerd Oscars, OK?" he advised me. On Saturday, Brown received an award for another technology he developed -- a camera suspended by four cables that can move freely through space. (It was used in films like "The Boy Who Could Fly," "Birdie" and "Highlander.")

"It's kind of a shame that we're sequestered off," Brown says of the sci-tech bunch. "We'll have our revenge some day."

And if Hollywood produced a major motion picture about the group, it would surely be called "Revenge of the ..."

Never mind.

Shares