Warning: the movie you are about to watch may challenge any faith you have in God. Do not, under any circumstances, allow your kids anywhere near "The Golden Compass," or its trailers. Be sure to quarantine them from Philip Pullman's "His Dark Materials" trilogy, the fantasy novels on which this movie is based. After all, your job is to protect your children, and your friends' children, from anything that might taint their notions of a Gandalf-like, gray-bearded old man of a God sitting on a throne in the sky, occasionally throwing down lightning bolts or raining shafts of light through the clouds.

And while you're at it, perhaps you should stop reading this piece too.

Talk about Philip Pullman has reached a fever pitch over the last few weeks in anticipation of the release of "The Golden Compass." Many Catholics and evangelicals across the country are frantic that the movie might inspire parents to march off and buy Pullman's novels for delivery and unwrapping on, of all days, the day of Jesus' birth. Some people are acting as if Pullman's award-winning books are anti-Christian stealth missiles aimed at children's souls and set to explode on impact.

But what started as a few angry press releases and a flurry of mass e-mails warning people to beware of, boycott and ban all things Philip Pullman has turned into a frightening reality in which Catholic principals, librarians and teachers all across the United States and Canada are being told by their diocese to remove "His Dark Materials" from their shelves and classroom curricula.

But who is really endangered by all this Pullman hysteria? I worry that the species actually at risk of losing their faith as a result of all the mud being slung about Pullman's exquisite rereading of the biblical book of Genesis are those Catholics who have read the trilogy and adored it, or (God forbid) had already given it to their kids. I worry that these lovers of great literature now feel like they sit on a dirty little secret that, if revealed, might make them persona non grata in the Catholic world they call home. But, since when are believers supposed to choose between their faith and their imagination? Between the joy of reading and the joy of sects?

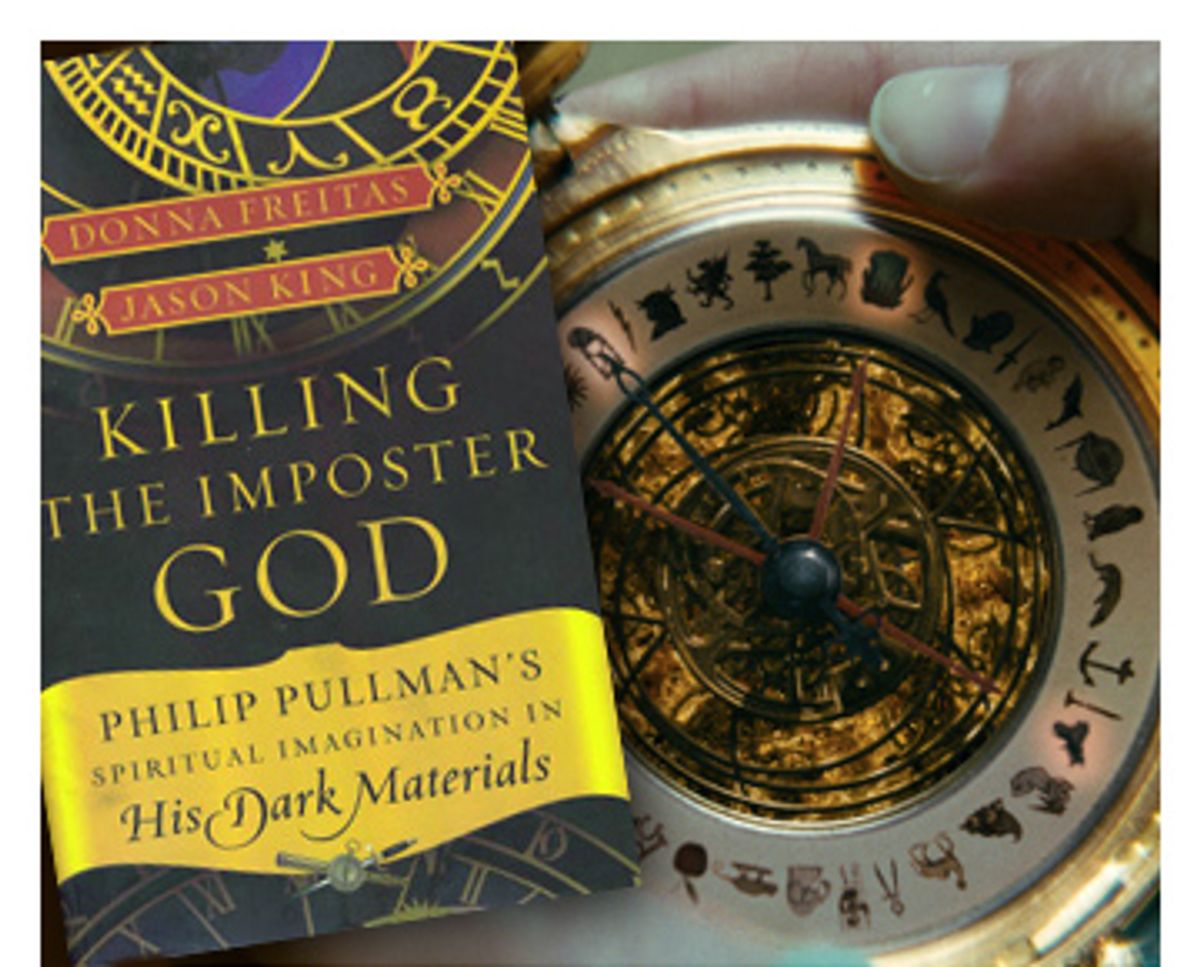

I recently published (with Jason King) a book called "Killing the Imposter God: Philip Pullman's Spiritual Imagination in His Dark Materials." I wrote this book, which portrays Pullman as a theologian rather than an atheist, and a rather Christian theologian at that, because I love "His Dark Materials." And because I am a Catholic. I don't see any contradiction between the two.

I can't help wondering, though: Somewhere in my love and interpretation of this trilogy, did I accidentally become a heretic?

A few weeks ago I was only half-kidding when I told friends I was worried that my own open approval of this story -- one in which I see an exquisite and Christian vision of the soul, virtue, salvation and (shudder) the feminine divine, aka Wisdom-Sophia, or the Holy Spirit (yeah, Her) -- might lead angry mobs to my doorstep. But now the idea seems less funny and more, well, possible.

Can those of us who are fans of Pullman still call ourselves Catholic, or will we have church doors slammed in our faces, our voices silenced at Catholic events? Is there something deeply wrong with our souls, which have found wonder and joy, and perhaps even God, in a series of books that are now being removed from library shelves at Catholic schools across the country? Are we lovers of the imagination a poison coursing through the veins of the Roman Catholic Church, or is the Church large enough to open itself up -- or at least to tolerate -- those of us who cannot in good conscience toe a party line intent on denouncing a movie the boycotters have not yet seen and books most of the banners have likely not yet read?

Allow me to plead my case, for I think I am innocent. (Though I fear I might be on trial, or even be found guilty without a trial.)

It's been almost a decade since my initial discovery of "His Dark Materials," and with it my near-fatal dive into the (apparently) heretical waters in which I am now swimming. I was a grad student in my 20s at the time, studying religion and theology at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. It was a Sunday like any other -- I was reading the New York Times Book Review, looking for a good novel. I read Gregory Maguire's review of "The Subtle Knife," and promptly headed out to my local bookstore to pick up a copy of it and its predecessor, "The Golden Compass." I read both books, and loved them so much that I agonized over the almost three years it took for Pullman to deliver the third book in the trilogy, "The Amber Spyglass." This book was released on my birthday. I thought it must have been divine providence.

By the time I embarked on reading "The Amber Spyglass" (and rereading the preceding volumes), I was steeped in the work of feminist and liberation theologians, in particular their new visions of God and their creative reimaginings of God's relationship to us. I'd pored over the writings of medieval women mystics who spoke in new (to me) and thrilling ways of the soul, the divine and the intimacy possible between humans and God. I'd been enthralled by the sixth-century thinker Pseudo-Dionysius, the Areopagite, whose via negativa speaks of a "negative path" to God that involves a process of conjuring up and then leaving behind every scrap of God, because these words and these images do nothing other than stand between us and God, barring the door that might otherwise give us access to the divine.

So as I read "His Dark Materials" in full for the first time I was enthralled not only by Pullman's magnificent story but also by his extraordinary theology. In fact, I saw theology all over the place in these novels. I knew that after my classes and exams and dissertation were over, I would soon return to these books as a scholar, to sort through the spiritual and religious themes layered (unwittingly in many cases) in Pullman's pages. I even imagined teaching a course some day devoted entirely to this trilogy, setting it in the context of Genesis and Milton's "Paradise Lost," ruminating with Pullman and my students on the Fall and Redemption and innocence and sin and salvation. Several years later, a colleague and I sat down to write a book on Pullman as a reluctant theologian and "His Dark Materials" as a religious classic.

All of this took place years before this controversy broke out.

But here I am now, in the middle of it all, having long ago staked out my position on Pullman and his trilogy, a position I will not recant, and wondering whether the religious tradition in which I was raised and of which I still count myself a member would ever welcome me again.

For the last few weeks I've been poked and prodded, tested and retested by the press about my opinion that Pullman's "His Dark Materials" is not only one of the best reads of my lifetime but also a work of theological magnificence. The president of the Catholic League, Bill Donohue, issued one press release that labeled me pathetic and embarrassing, and another that, to the delight of my friends and family, called me "Dr. Spin" -- as in Pullman's official Catholic spin doctor. Among bloggers especially, my identity as a Catholic has been called into question, dismantled and denied. Apparently, liking "His Dark Materials" -- never mind loving it, as I do -- is enough to damn you in the God-fearing, agenda-thumping, always so careful to be kind and respectful in a Good Christian manner blogosphere.

I am deeply saddened by the very real effects of a small group of angry Catholics on the wide-reaching world of Catholic schools. Christianity is built on stories, and grand stories at that. In many respects it was my Catholic faith that taught me to love stories. In the process I became a storyteller too. But more important, I became someone who appreciated good literature of all kinds, and with it the grace of sharing it with people I love.

I don't see any contradiction between loving God (whoever S/He may be) and loving a good story, even a challenging one, like Pullman's, that has the power to transport us from here and now to another place and time, to forget time altogether as we journey into another world with a young girl (Lyra) and boy (Will) on a fantastic adventure. God is big enough, I think, to coexist with Will and Lyra. It is the critics of Pullman's novels who are trying to make Her small.

Shares