In the moments before the January 2001 New York Film Critics Circle got under way, the winner of the group's best-actor award, "Cast Away" star Tom Hanks, stood at the center of a circle of journalists and industry colleagues shaking hands and making small talk when a party guest approached, removed a microcassette recorder from his coat pocket and played a tape of his toddler-age child reciting a couple of Cowboy Woody's lines from "Toy Story 2."

"Yes, indeed," Hanks said. "I am America's babysitter."

He was only partly right. Thanks to repeat showings of the "Toy Story" films on DVD and cable, Hanks' animated alter ego has doubtless mesmerized millions of tots for untold numbers of hours. But America's true babysitter is Hanks' employer on the "Toy Story" films, Pixar, along with the other animation houses, including Disney and DreamWorks, that have competed for pieces of the family entertainment business that Pixar has dominated since "Toy Story 2" came out a decade ago.

Granted, Pixar wasn't created to crank out lovable time killers. The company's guiding lights — president and co-founder Ed Catmull and longtime creative director (and sometime movie director) John Lasseter — trumpet Pixar's ability to make commercial entertainment with charm, visual wit and a sense of moral responsibility, and with rare exceptions (the stupefyingly lame "Cars") they walk the walk. "A Bug's Life," "Monsters, Inc.," "Finding Nemo," "The Incredibles," "Cars," "Ratatouille," "Wall-E," "Up": We're not talking about Hanna-Barbera's Carter-era trash factory, but a studio that takes pride in its work.

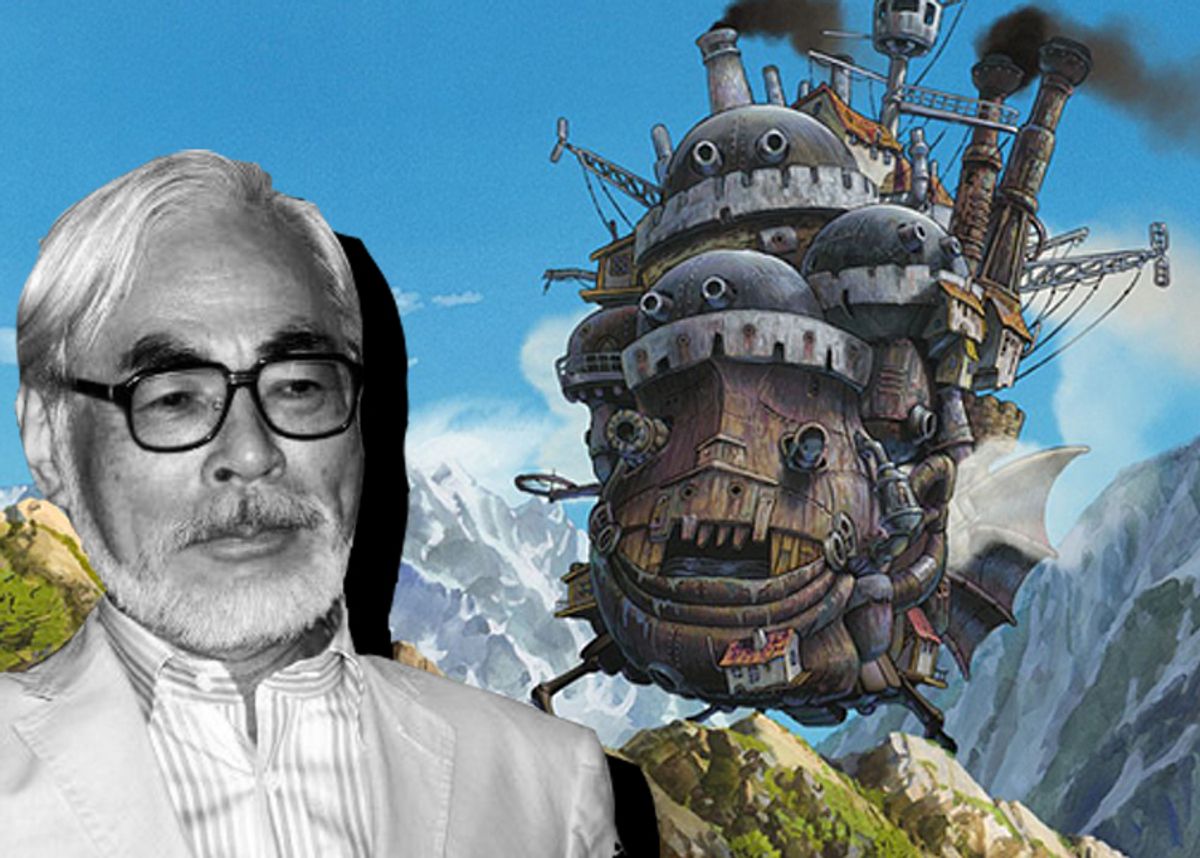

No, I'm calling Pixar "the Babysitter" for the same reason that I'm classifying a studio as a director in this series: For rhetorical purposes, the better to contrast their remarkably unified output (that is, the Pixar "brand") against the work of Hayao Miyazaki, the founder of Japan's Studio Ghibli and arguably the most innovative and accomplished mainstream animation auteur after Walt Disney himself.

Miyazaki, who turns 69 next week, is still underappreciated in the United States. His last four features, "Princess Mononoke," the Oscar-winning "Spirited Away," "Howl's Moving Castle" and "Ponyo" were released stateside by Pixar's parent company, Disney, in dubbed versions, earning critical praise but not a fraction of Pixar's usual box office haul. Worldwide, however, Miyazaki's last three features as director made about $700 million. That's a Hollywood-studio-level number that's noteworthy on its face, but it's even more striking for those who appreciate Miyazaki's willingness to depict situations, emotional conflicts and moral struggles that neither Pixar nor any of its U.S.-based competitors would dare touch. If Pixar is the Babysitter — the smart, likable professional you can trust — Miyazaki is the Grandfather: a wise and beloved elder who understands kids as deeply as (in some ways more deeply than) their parents do, and knows that while the ability to delight and comfort children is a rare talent, it's not the only one worth cultivating.

I'm not here to run down Pixar. Its films are consistently good, sometimes enthralling. They thrill and amuse. Sometimes they move (the "When She Loved Me" montage from "Toy Story 2" and the first few minutes of "Up" are as elegantly composed and edited as they are sentimental). On occasion, Pixar evangelizes; thanks to the green polemics of "Wall-E," generations of kids will subconsciously associate pollution and gluttony with apocalypse — an agitprop victory that five decades' worth of Saturday morning TV messages can't claim.

And for sheer filmmaking craft, Pixar is tough to beat. Nearly every moment of its best work is both dramatically efficient and compositionally sturdy, sometimes gorgeous (the assembling of the fake bird in "A Bug's Life"; the chase through the dimensional door assembly line in "Monsters, Inc."; the wordless opening section of "Wall-E"; the action-packed and at times almost abstractly beautiful final stretch of "The Incredibles"). From Pixar's early, Oscar-winning short films to the "Toy Story" movies through this decade's unbroken string of hits, the studio has earned a deserved reputation for making features that feel at once polished and personal. Lasseter and his regular stable of filmmakers — a group that includes Pete Docter, Brad Bird and Andrew Stanton — have a knack for smuggling poignant or meaningful moments into otherwise light entertainment. Think of the fearsome critic Anton Ego in "Ratatouille" as he samples the title dish, flashes back to childhood and drops his pen on the floor, his momentary return to innocence showing young viewers what it means to be transported by art; or the title family in "The Incredibles" working in concert against their enemies, literally discovering powers they didn't know they had, and illustrating the idea that a family is stronger united than divided; or ace frightener Scully in "Monsters, Inc." realizing his power over children and seeming disturbed instead of proud — an introspective moment that might help children understand parents, and parents understand themselves.

At the same time, though, Miyazaki's presence points up the limitations of Pixar, which are the limitations of American commercial entertainment generally. Pixar landed on this list, and in the penultimate slot, not strictly on its own merits (which are, as I've said, considerable), but because of its imaginative dominance of family entertainment, and its capacity to shape future moviegoers' sense of what animation (and entertainment) should be. Pixar represents the best of what American commercial filmmaking is. But Miyazaki shows what might be possible without Pixar's inhibitions (or constraints, take your pick).

Factor out the few dark and disturbing moments in Pixar's films this decade (there haven't been many, really) and you're looking at a body of work that's fairly easy for even the youngest children to grasp and process, and ultimately not challenging compared to Miyazaki. In Pixar films, good characters sound (and usually look) conventionally lovable. Good and evil are clearly defined, and no "good" character's goal is left unmet. And no potentially confusing or disturbing apparition, incident or twist is left unexplained for long.

Contrast this with Miyazaki's much freer and deeper approach to family entertainment, and you start to see the aesthetic gulf between his work and Pixar's (and, by extension, between the splendid array of animation that thrives internationally and the homogeneous, Pixar-inspired type that dominates U.S. screens). Miyazaki's films are just as visually imaginative as Pixar's and often more so — more painterly and less beholden to the rules of "realism." More importantly, they are never content to define characters as good or evil, or even mostly good or mostly evil, and be done with it. Through a canny combination of sharp draftsmanship, clean animation and simple dialogue, Miyazaki throws children (and often adults) off balance, leaving them unsure what to make of a certain character or situation and forced to grapple with what Miyazaki is doing and showing.

The little spider servants, the white dragon and the giant-headed old woman Yububa in "Spirited Away" seem scary, or at least intimidating, on first glance, and never quite lose those qualities (especially Yububa) even after they're revealed to be benevolent creatures. In "Ponyo," about the friendship between a land-dwelling boy and a half-human, half-fish sea creature, we're primed to react to Ponyo's wizard father, who fears and loathes surface dwellers, as a killjoy who will eventually come around; but even at the end of the film, dad's apprehension hasn't been allayed, and Miyazaki has made such a point of showing us humanity's blithe poisoning of the sea (Ponyo's dad has dedicated himself to cleaning it up) that we can't root for a conventional, can't-we-all-just-get-along finale.

With its spindly chicken legs, clanking engines and scaly iron armor, the title structure in "Howl's Moving Castle" is classically nightmarish, but it's revealed as a wondrous place (albeit one staffed by neurotics such as the passive-aggressive and very needy fire demon Calcifer). But the title character is one of the most complicated heroes in mainstream animation this decade — a teenager who's deeply insecure and lonely, and thus ripe for manipulation by competing kingdoms that recruit him as a warrior. Howl carries himself like an entitled prince, but he's a pawn.

In place of the conventional, reductive versions of morality and psychology shown in Pixar's films, Miyazaki gives us something closer to actual experience, treating good and evil not as a binary equation but as a sliding scale and presenting people (and characters) that often don't know why they do what they do and latch on to reductive explanations at their peril. Characters can be scary and then friendly, threatening and then reassuring, honest and then misleading; they can shift identities and change shape, succumb to spells and then break out of them. That Miyazaki built so much of the plot in "Spirited Away" around the mysterious presence of a character named No-Face (his visage an expressionless mask) is hardly accidental. It's what inside that counts, and Miyazaki takes the sap out of that formulation by making his characters' interiors as malleable — and often as unformed — as their exteriors. A boy becomes a dragon becomes a boy again in "Spirited Away"; the rooms change shape and size in "Howl's Moving Castle"; Ponyo becomes fond of the land (and develops a taste for ham!) and sprouts the budlike beginnings of legs. Watching Miyazaki's movies, one gets the sense of humankind (and its fantastical stand-ins) as creatures in a permanent state of evolution, able to transform from year to year, week to week, even moment to moment. In Miyazaki's work, people are what they choose to be, but they're also what other people have decided they are — and the tension between those two definitions (plus the complicating factor of characters not having a strong sense of themselves, much less knowing what they want from life) makes Miyazaki's features more complex than almost anything being made in the American studio system, animated or live action.

Parents will testify that a child who sees his or her first Miyazaki film after a steady diet of Pixar and Disney is apt to experience a perhaps troubled reaction, much deeper than "That was fun" or "I liked it." Miyazaki challenges every preconceived notion about family entertainment that Pixar and its ilk conditions children (and adults) to have. Pixar's very best work this decade — "The Incredibles," "Wall-E" and "Up," and moments of "Monsters, Inc." and "Finding Nemo" — is wonderful; it gives children lots to see and a fair amount to feel. But Miyazaki's work does more than that. His art is engrossing and beautiful but also challenging. He urges children to understand themselves and the world, and then shows them how. The Babysitter mesmerizes children. Grandfather changes their lives.

Shares