Before Dennis Hopper, who died Saturday of prostate cancer, became a rebel filmmaker or a generational symbol or a legendary debauchee or a Hollywood aesthete and Renaissance man (or a George W. Bush Republican and then an Obama voter), he was an actor. I'm inclined to believe that all the roles Hopper played across 74 years of life and more than 50 years of moviemaking were aspects of his acting career, of his passionate interest in the mysterious fusion of being, imagining and pretending that allows you to be yourself and someone else at the same time.

Hopper appeared in a handful of memorable films -- "Apocalypse Now," "The American Friend" and "Blue Velvet," along with his own "Easy Rider" -- and a seemingly infinite litany of forgettable ones. Even when he performed in children's TV or straight-to-video Eurothrillers or the 1993 film version of "Super Mario Bros.," you always had the feeling that Hopper was performing a kind of existential high-wire act, perhaps more for himself than the audience: How much of his own soulful madness would he let out? How much of the inanity and mediocrity around him would he absorb?

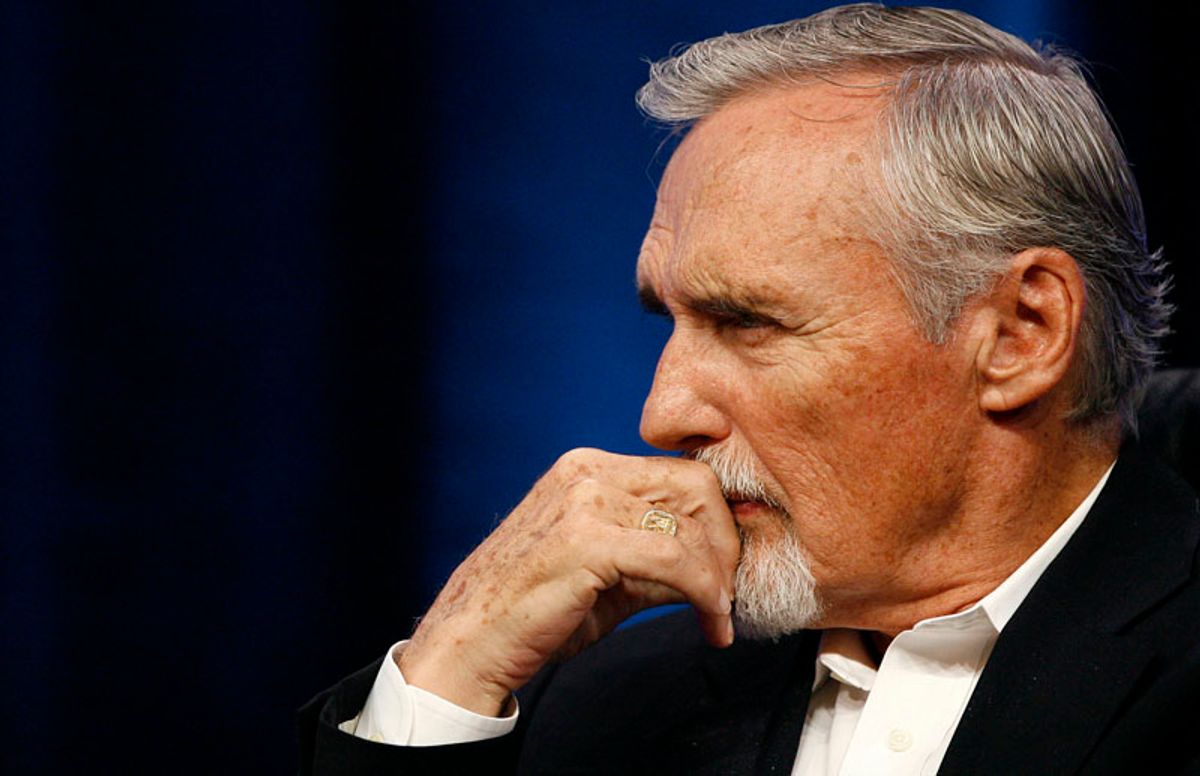

On the one occasion when I met Hopper, at a film-festival party in San Francisco about 15 years ago, he gave a vintage performance, drinking wine and laughing it up with a group of people he barely knew (or, in my case, didn't know at all). He wore a white linen suit and a trim goatee, regaled us with yarns from his heyday as a "total madman" in the 1960s, and looked terrific against what I remember as a crisp, sunny day. At some point his female companion -- I'm not going to try to figure out who that was, and it doesn't matter -- stalked off after some heated private conversation, but he didn't seem concerned.

When I asked Hopper what he remembered most about James Dean, with whom he appeared in "Rebel Without a Cause" and "Giant," his demeanor changed. He became intensely earnest, explaining that Dean had changed his approach to acting and to life. Hopper had begun acting in television at a time when it was all about clarity and economy, he explained: You hit your mark, you said your lines clearly, you made your exit. Then he got on the set of "Rebel Without a Cause" (his film debut) and met Dean, who had been studying under Lee Strasberg at the Actors' Studio in New York.

"Here was this kid, Jimmy -- I mean, he was older than me, but he was still a kid," Hopper said, "and the stuff he was doing was amazing, it just blew me away." (I won't pretend these are verbatim quotes; this is the conversation as I recall it.) He remembered Dean rolling around on the carpet of the set that was supposed to be the Stark family's Los Angeles home. "I asked him what the hell he was doing. I mean, you just didn't do that. It was completely from another planet." Dean explained that Jim Stark, his alienated teenage character, had spent a lot of time on that carpet and was intimately familiar with it. He needed to know what it felt like.

Along with Marlon Brando, Dean was one of the principal vectors for the transmission of Strasberg's "Method acting" approach into the Hollywood mainstream, and Hopper became an eager disciple. (Publicity photographs from "Rebel Without a Cause" show Hopper reading Stanislavski's "An Actor Prepares" on the set, which can only have been Dean's idea.) After Dean's death, Hopper abandoned Hollywood for Manhattan and spent five years studying under Strasberg. In later years, as the Method came to dominate American film acting, several of its practitioners became much bigger stars than Hopper: Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Sean Penn, along with Hopper's close friend Jack Nicholson. But I'm not sure any of those men internalized the Method, or pursued its philosophical and psychological dimensions to their logical extremes, the way Hopper did.

Viewed narrowly, the Stanislavski-Strasberg Method is a means to an end: An actor employs his own emotions, memories and sensations in order to portray a character in more lifelike and convincing fashion. Hopper seemed to develop his own expanded, synthetic interpretation, probably shaped by his appetite for consciousness-altering substances, avant-garde art and thorny philosophy. Every Hopper performance was just a facet of his lifelong, overarching performance as Dennis Hopper, and the professional separation most actors maintain between themselves and their characters evaporated entirely. Apocryphal or not, the story of Hopper's phone call to David Lynch after he had read the script for "Blue Velvet" is on point: "You have to let me play Frank Booth. Because I am Frank Booth!"

Of course Hopper wasn't really an amyl-nitrite-huffing, psychopathic rapist any more than he was a disgraced Indiana basketball coach (as in "Hoosiers") or a disgruntled bomb-squad officer (as in "Speed"). But he pursued roles as dangerous and damaged characters, at least in the second half of his career, with a fervor that suggests he found them personally therapeutic as well as financially rewarding. Frank Booth was a revelation because he was horrifyingly, recognizably real, in a way movie villains hardly ever are. Even with his exaggerated vices and mannerisms, his foulness was rooted in genuine pain. (And Frank's profane preference for Pabst Blue Ribbon over Heineken launched a trend among young consumers that endures two decades later; the brewery should have paid Hopper and Lynch a lifetime commission.)

Right after his breakthrough 1986 performance in "Blue Velvet," Hopper starred in the hoops drama "Hoosiers," a commercial success which garnered him, amazingly enough, the only Oscar nomination of his entire acting career. (He had been nominated for best original screenplay for "Easy Rider," along with co-writers Peter Fonda and Terry Southern.) After that, he returned to the director's chair for the first time in 17 years, making the solid L.A. gangland drama "Colors," a midsize hit. A late-career renaissance as a star character actor and indie auteur beckoned, but Hopper, in entirely typical fashion, just didn't seem to care about that, or even to think about himself in conventional, careerist terms.

He spent the last 20-plus years, in fact, doing about the same stuff he did for the 20-plus years before that: Acting feverishly, in whatever context presented itself. You've seen or heard Hopper in big, noisy movies ("Speed," "Boiling Point"), smaller, quieter ones ("Red Rock West," "Jesus' Son"), TV series ("24," "E-Ring," "Crash") and a baffling array of video games, documentaries, animated specials and indistinguishable direct-to-video crime films. (Have you seen "Lured Innocence"? "Bad City Blues"? "The Spreading Ground"? If so, I salute your devotion. Now, please get professional help.)

From a normative, celebrity-centric point of view, Hopper's career has been a series of failures. He failed to cash in on his early acclaim as Dean's co-star with major movie roles, failed to turn his anarchic, lightning-in-a-bottle success with "Easy Rider" into a directing career, and failed to turn his post-"Apocalypse Now" comeback into anything approaching the brandy-snifter, lion-in-winter act we expect from aging actors. But each of those failures stemmed from the one before it, and Hopper used each one to create the Zen bon-vivant persona that was fed by all those deranged guys he played on screen but was bigger and more satisfying than any of them.

At some point in the late '50s or early '60s, Hopper must have realized that a guy with an aquiline face, ferocious eyes and the body language of a rabid terrier wasn't going to become a movie star. So he made a living on TV and became an important portrait photographer, as well as an autodidact art collector who helped introduce modernist and postmodern art to Los Angeles. He used his Hollywood outsider status as creative fuel in making "Easy Rider" with Fonda, Southern and Nicholson. In all its post-adolescent male angst and self-centered artistic ambition -- director Henry Jaglom was called in to edit Hopper's 220-minute version into something releasable -- is an awkward mishmash of a movie, but an enormous cultural milestone.

In an era when virtually every Hollywood actor and director ingested all sorts of elaborate chemicals, Hopper became the media's whipping boy for drug abuse. After the critical and commercial debacle of "The Last Movie," his semi-experimental follow-up to "Easy Rider," his directing career lay in ruins and he evidently decided to live the part fully. But the idea that Hopper's ensuing European exile was nothing but lost years of cocaine and crap movies is at least partly undermined by the evidence, most notably his terrifying turn as Patricia Highsmith antihero Tom Ripley in Wim Wenders' brilliant "American Friend" (for my money, the second-best Hopper performance of all, after "Blue Velvet").

Hopper clambered back into the American limelight with "Apocalypse Now" and got partly and conditionally sober in the early '80s and moved on to play Frank Booth and Frank Sinatra (in an Australian film I've never seen) and supervillain Victor Drazen in "24" and whoever he played in an animated special called "Santabear's High Flying Adventure." He eventually got old and sick and now he is dead, leaving behind one of the strangest peaks-and-valleys legacies in showbiz history. I think the whole time he was rolling around on the carpet. In order to be Dennis Hopper from one moment to the next, he needed to know what it felt like.

Shares