Gavin O'Connor's feature directorial debut, "Tumbleweeds," premiered at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival in January. A sweet, sharply written portrait of an unconventional mother-daughter relationship, it tells the story of flirtatious Mary Jo Walker and her preteen, precocious daughter Ava, as they move across the country in search of the right ex-boyfriend with whom to settle down. By the end of the film, people were whispering to each other about the remarkable, winning performance of Janet McTeer, a 39-year-old British actress in her first starring screen role.

The film was picked up by Fine Line before the week was out. "Tumbleweeds" walked away from Sundance with every filmmaker's fantasy: studio distribution and the Filmmakers Trophy.

Although new to the screen, McTeer had a similar impact on the New York theater world in 1997 with her bold, Tony award-winning performance of Nora in Ibsen's "A Doll's House" on Broadway. A household name in English theater (and what household doesn't know the English theater?), McTeer has had a long career of impressive London stage credits and a few dabbles into film and television. Fine Line is betting that "Tumbleweeds" will make her a star, and indeed it seems like a possibility. This week, the Independent Feature Project's Gotham Awards will be honoring her with the Breakthrough Award.

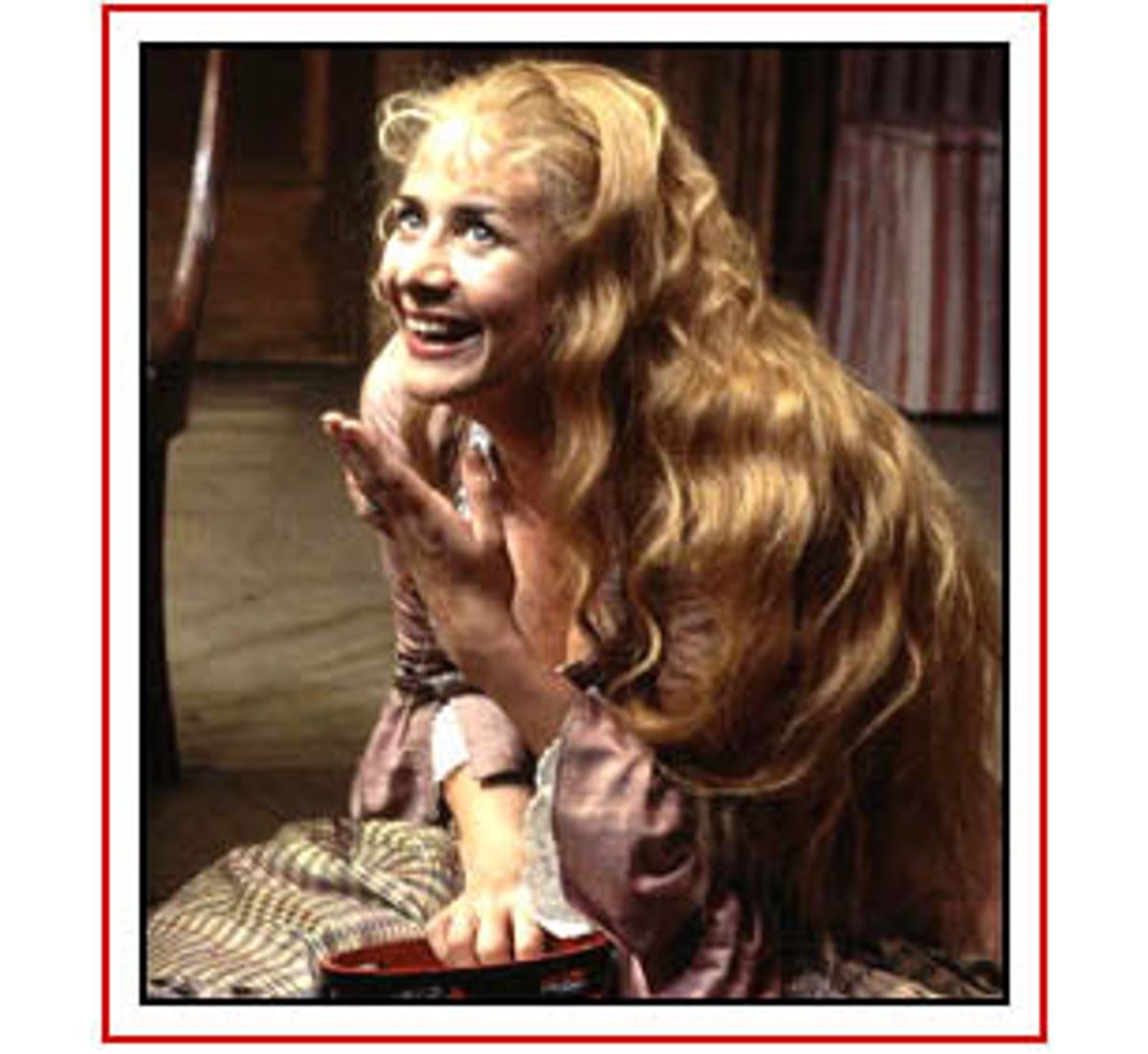

I spoke with McTeer at the Toronto International Film Festival last week, where "Tumbleweeds" was making the first of a few stops on the festival circuit before its release in November. McTeer is such a convincing Southern belle in the film that to hear her confident, conversational English lilt actually captures you by surprise. Gone is the long, wild hair, the come-hither body language, the mischievous naiveti. McTeer is smart and aware and fearlessly self-defined. Only the laugh seems to remain the same.

Your first starring role is in a bona fide independent film -- first-time feature director, no studio backing, no high-profile actors attached -- was that a deliberate choice? Had you turned down studio projects before accepting this one?

Yes, I turned down two studio projects in fact, because I didn't like them enough. They were quite nice parts but not interesting for me.

So what attracted you to "Tumbleweeds"?

I loved the script, I loved -- even as an early draft I loved it, though it really wasn't finished and I knew that. I loved the whole feeling of it and all that. Then I met Gavin and I really, really liked him. We got on brilliantly. I met Angela and I loved her. That for me was it, you know? Because they were just people I knew I wanted to work with, and they were really great people and really committed and passionate about the work that they do, and I've never done a job for money. I've only ever done it because I've loved it. And I've always managed to pay my rent.

Your American accent was so convincing at Sundance, that people actually gasped when they heard you speak after the screening. How did you prepare for the accent? For the real Southern feel of Mary Jo?

Two things. I had a few lessons with a voice coach and I learned, you know, phonetically, the technical route. I also watched films: "Coal Miner's Daughter" and "Bastard Out of Carolina" at least a hundred times. Anything Southern I could get my hands on I would watch and I would listen to, trying to get the feeling what it must be like to live in a place that has so much space, because I think space really governs the way they talk. And then I went to North Carolina as well -- Asheville -- and I stayed there for a while with a family, just went out with them, had dinner with them, chatted with them and went around and saw people and listened and sat in the mountains, imagining what it must be like to grow up in a place like that. I talked to lots of people there. I really put it together like that. I learned it in the end from many points of views. Technically I had a whole list of sentences, there are about 30 of them, and each is for a different sound -- like "The fascinating actor Harry McCann married Ann Hamilton" -- that's the "a" sound, you can do it any accent.

[McTeer switches to the Southern accent, and its inflections seem to take over her whole body. Her eyes become droopy and her mouth turns up slyly at the corners.] "That fascinatin' acta Harry McCayan, he maaarried Ann Haamilten."

So that's how I did it. I would listen to a lot of country music, I would play tapes of people talking while I was cleaning the apartment, I'd have it on in the background, and then I would practice every day sort of on and off every day for about two months.

After years of preparing for theater roles, was your preparation for this film different?

No. It's actually the same, absolutely, totally. You start knowing nothing and then you piece together things that you actually know. You know where she comes from, you know she has a daughter, you know she's had all these relationships with men. And then you sort of explore every avenue of those things that you know. Somehow you try to relate to each little bit, the bits that are different; you find a place where you can relate to those that are different from you. Sort of like, she's over there and I'm over here and somehow the character is in the middle.

But then was it jarring to go from the continuity of theater to shooting out of sequence, doing multiple takes, and breaking the part down into its smallest parts?

Not really. It's a different performance technique is all. Really what you're doing when you're rehearsing a play is you're saying, my character starts here and she ends there. How do I get from here to there? What happens between here and there? And that's exactly the same in film. When you prepare for film you go, alright this is where she learns this, and so on, like a simple blueprint to hang onto, you know? So that when you are coming to do a scene, you go OK, it's there, so I'm there, as opposed to something else at a later moment.

The idea is that you have technique and discipline. Someone asked me a question about training and did I think that training wrought good actors. And I got incredibly angry -- we Brits train quite a lot. Because to me talent is being able to fly, training is having the feet to run you along and get off the ground. You shouldn't see the feet when they're flying. But if you don't have them you'll never fucking take off. Not in my opinion. Or you might fly once or twice, but you'll always be the same bird.

If you have a good, sound training and a technique, it's like you know which questions to ask, you know how to create that blueprint of the character for yourself so that when someone asks you, do this scene now and that scene next, and you [the audience] say, gosh, she looks so different, it's because I know what I'm doing. I know where I am. I know whether my character has opened up or whatever. Even though all that technique and machinery is hidden in the moment which is spontaneous and real and free. You fly. And you shouldn't see the machinery. It's my theory and I'm sticking to it!

The relationship between Mary Jo and Ava is so frank and open, and yet you are acting with a child who may not have the training that you are talking about. How do you establish that kind of intimacy with the kind of discipline you describe, if that is not her experience?

It's not quite the same. I respect Kimberly's talent as an actor and I respect her as a person. She's also someone who has been blessed with parents who have taught her how to communicate. When I met her for a day or so I realized the way I thought we were going to get this was to be really frank with her, really open with her, and say, "This is what I think! What do you think?" And when she didn't know the answer, we would talk about it together. "What about this? What do think she thinks? What is she thinking now? What does she think about sex? Has she had her period yet? If she hasn't, how does she feel about that? Is she nervous, do you think?" We would be incredibly frank, in the rehearsal room -- well I wouldn't say it was a rehearsal because I didn't know her then -- to gauge whether that would make her uncomfortable or comfortable or whatever. And actually she was fine, because she has these great parents. Particularly her mom, who talks very frankly with her about things. So consequently she has a frankness that she brings to the role. And as long as I and Angela and Gavin were all frank together, that paid off.

Being open is one of the things that makes Mary Jo a good mother to Ava, although openness can go too far in families, especially single-parent homes, where the parent puts pressure on the child to address adult decisions. Yet Mary Jo understands the boundaries of a parent-child relationship while at the same time she cultivates a true friendship with her daughter. That's a tricky position. Is that a choice Mary Jo makes, or an instinct?

I think it's to do with knowledge. Knowing the child. Knowing whether they would find something funny or whether it would upset them. Probably the truthful answer is that sometimes she's mistaken and sometimes she's right. But in general, because she's not conventional and she's seemingly spontaneous, that looks like there's no thought behind it but there is. I think she knows exactly what she wants to do. She wants to bring up her daughter as a friend. She wants to say my life is my life and your life is your life. And the choices you make are the choices you make. Except that she's still kind of ... she doesn't really listen or see the choices that she's making in her life. Isn't that what we all do sometimes? To play somebody who is really rounded is the key. Is to not say oh, I want her to be liked, or whatever. You don't. You have to say this is where something comes from. This is the full story.

Mary Jo seems to feel that she isn't capable of existing without a man and yet she would never impose that on her daughter.

The thing that she's trying to teach Ava is a real sense of self. A really good sense of self. She was never taught that. So she teaches her to be herself. What do you think? What color do you want to wear today? What T-shirt do you want to wear? You pick the fucking T-shirt. Wear whatever you want. They're your clothes. And she's never, "Oh you're going to school, therefore you should do ..." She's not that kind of a person. She doesn't believe like that. So consequently I think what she's done is say you're a wonderful person, you should do whatever you want to do. You like that person, be with that person. You don't, then you don't. She's teaching what she believes, not what she feels in her heart because that's not how she was brought up. And then of course Ava grows up enough to be able to say, "You know all that self-respect you taught me? Well, I have it. Well, could you take some of it back please? Could you have some yourself?"

[Mary Jo] teaches somebody something that she wishes she had, in a way, and then the daughter turns around and says, "Grow up. Do it yourself." I think that's the story of the movie. I think it's a very beautiful circle.

The itinerant nature of Mary Jo and Ava's life, the quest of something better somewhere else -- usually by moving West -- is a common theme in American folklore. Did doing this film change your preconceived notions of the American psyche?

In many ways I think it's not that dissimilar to any psyche anywhere. Which is: A generation will always wish to teach a future generation the things they never learned, the things they felt they didn't have. And that's what love is, really. In terms of the American psyche? It's very odd because she's so Southern. The American psyche is many and varied and different, you know? I think she's so much a product of a Southern upbringing. She so much identifies herself as a sexual being opposite a man. And without that she has no sense of self. And she has it hugely and she doesn't recognize it. She learns to recognize it through her daughter. I've learned a lot about the Southern psyche, I wouldn't say I've learned a lot about the American psyche in general.

How much of your career at this point do you want to commit to film? When you look back 20 years from now what do you want to have accomplished in this period?

I'm not really a five-year planner. If something comes up and it's fantastic, I'll say yes I'll do it, whether it's now or this year or next year that's fine. I tend to be ruled a little more in the moment. I know now I've done three movies back to back. Now I'm going home. I can tell you that much. I know I'm not working for a little while because I'm tired and I want to be with my family and my friends. Thereafter if somebody phones me and says it's a great job and I need it and I love it, I'll do it. I came to New York to do "A Doll's House" and suddenly all this happened and absolutely, why not? It's interesting, it's new, it's fascinating, it's challenging. I've loved every second of it. But it doesn't mean I won't go home and do some more theater. I will.

Shares